- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Good Soldier by Gary Mead in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS | |

LIST OF MAPS | |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS | |

INTRODUCTION: Neither Butcher nor Saint | |

1 | Whisky Gentleman |

2 | Polo Field and Parade Ground |

3 | ‘The Long Long Indian Day’ |

4 | ‘Hard Work in Hot Sun’ |

5 | Chasing Boers |

6 | ‘One of the Most Fortunate Officers’ |

7 | An Army Equipped to Think |

8 | ‘This War Will Last Many Months’ |

9 | ‘There Are Spots on Every Sun’ |

10 | The Somme |

11 | Passchendaele |

12 | Victory |

13 | Of Politics and Poppies |

14 | ‘Cause to Reverence His Name’ |

AFTERWORD | |

NOTES | |

BIBLIOGRAPHY | |

INDEX |

This book is dedicated to the memory of Charles Hemming – teacher and friend, and the finest example of the impossibility of ever really knowing anyone.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It is one of the pleasures of writing a book that one is frequently reminded of the innate kindness of strangers, who respond with generosity and warmth to a query for help that arrives out of the blue. Another is the process of discovery and acquiring greater understanding, and through that having one’s prejudices demolished. I owe considerable debts to a number of people who have been very supportive of my writing this book. At Atlantic Books, Toby Mundy, publisher, has been very patient and encouraging; Angus MacKinnon, who commissioned the book, has been a tower of calm strength and has been unflagging in his intellectual engagement in the project – no author could wish for a better editor; Emma Grove has taken a keen interest and helped in numerous ways to steer it into print. Barry Holmes and Polly Lis gave unparalleled professional service in the editing process. My literary agent, Christopher Sinclair-Stevenson, has shown his usual unswerving confidence and extended unfailingly kind and regular morale-boosting. Colm McLaughlin, curator of the Haig Archive, and other staff at the National Library of Scotland (hereafter NLS), pointed me in fruitful and previously unexplored directions. Writers on the First World War and Douglas Haig owe a large debt to the 2nd Earl Haig for enabling access to the Haig archive at the NLS; I additionally owe a personal one for his agreeing to meet me and talk about his father, Field Marshal Earl Haig. Professor Hew Strachan of All Soul’s College, Oxford University, whose grasp of the events and personalities of the First World War is unrivalled, read the manuscript and placed some episodes in a wider, more complex context than I had previously considered, as well as ensuring that some mistakes were suffocated before print. Those that may inadvertently remain are entirely my responsibility.

Denise Brace at the Museum of Edinburgh was inordinately helpful in photographic research, as were Dr A. R. Morton at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst and David Fletcher, historian at the Tank Museum, Bovington, and archivists at the Imperial War Museum in London. Michael Orr provided much useful material from the records of the Douglas Haig Fellowship. Andrew Jefford gave me new insights into the Scottish whisky business. Matthew Turner helped me understand more of the difficulties of trying to measure the relative value of money over time. Martin Hornby of the Western Front Association provided me with useful background research materials. Colonel John Wilson, editor of the British Army Review, generously provided me with archive resources. Elizabeth Boardman, Archivist at Brasenose College, Oxford University, yielded fresh insights into the shifting perceptions of Haig.

The London Library is a remarkable entity, having under one roof so many of the essential materials that would otherwise be almost impossible to consult. The literature on Douglas Haig, the British army he spent his life serving, and the First World War is staggeringly vast and daily added to; a book of this kind could not exist without the work of many previous scholars and writers. The bibliography should be understood not as claiming a spurious authority but rather as a gesture of appreciation to some of those who have toiled before. Last but far from least, it would have been impossible to get this far without the support of my wife Jane and our daughters Freya, Theodora, and Odette, who bore this lengthy enterprise with fortitude, fun and frankness – they stoically endured a lot of absent fatherhood.

LIST OF MAPS

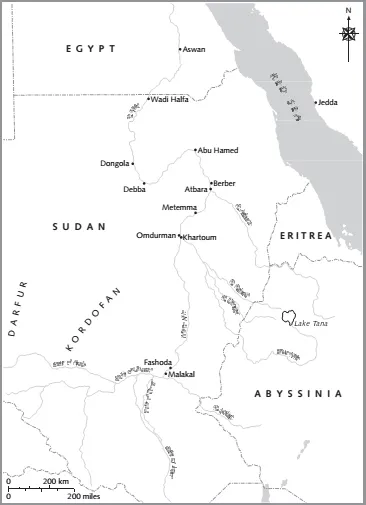

The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, 1898

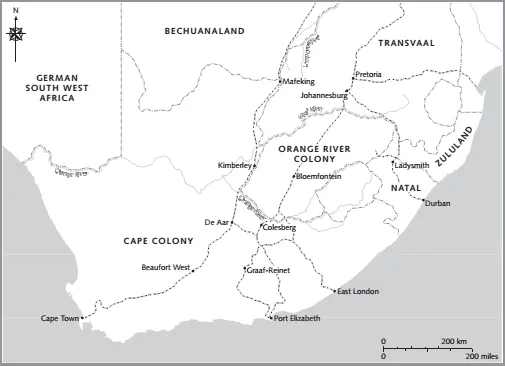

South Africa, 1899

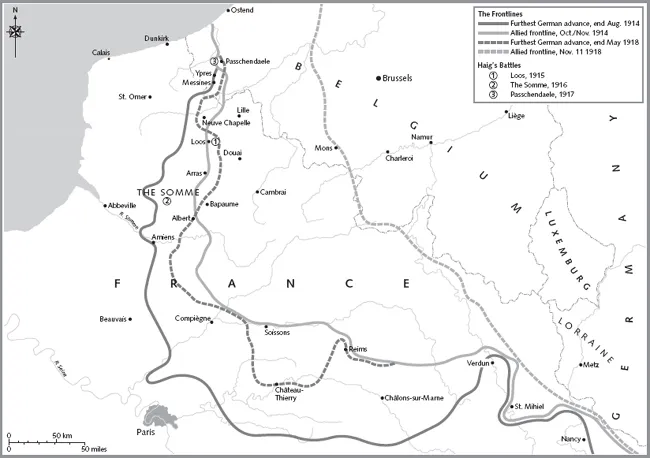

The Western Front, 1914–1918

South Africa, 1899

The Western Front, 1914–1918

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Section 1

Young Haig

Haig family at Cameronbridge

BNC Wine Club, 1882

Sandhurst 7th Hussars, Secunderabad

Kitchener in the Sudan

Haig and Henrietta

Douglas and Dorothy Haig on their wedding day

Section 2

Boer Commandos

1912 aircraft

Haig with King George V

Cavalry at Mons

Haig with Lloyd George, General Joffre and Albert Thomas in France

Haig with Sassoon at GHQ

Passchendaele

Mark V tanks

Section 3

Haig at peace march

German soldiers returning home

Field Marshal Haig

Haig with wife and daughters

Haig and Doris

Boy scouts

Haig’s coffin

The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, 1898

South Africa, 1899

The Western Front, 1914–1918

INTRODUCTION

Neither Butcher nor Saint

There is little doubt that Haig was an idiot.

The unofficial Australian view; see www.diggerhistory.info

Arguably he killed as many of his own men as Stalin and Hitler put together.

Andrew Grimes, Manchester Evening News, November 1998

As any historian who has tried even mildly to be revisionist about Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig on television will acknowledge, there is a corpus of opinion which is not overly interested in the facts because it has already made up its mind.

Richard Holmes, foreword to Blindfold and Alone, Cathryn Corns & John Hughes-Wilson, Cassell, 2001

Douglas Haig’s misfortune as a British general is that he was born and schooled in one era but had to fight his most important battles in another. His Victorian upbringing could not prepare Haig, nor anyone, for the stalemate of the Western Front’s trenches and the incremental technological improvements which gradually made possible the grudging victory of November 1918. Haig was a cavalryman by profession and faith, who never felt comfortable using the telephone and never travelled in an aeroplane. His experiences in Sudan and South Africa had more in common with that of the Duke of Wellington – who died less than a decade before Haig’s birth – than the battlefields of 1914–18, which saw the tank supersede the horse in attack, radio communications displace the telegraph, and aircraft come into their own as the eyes of command. Haig’s inexorable rise to the highest reaches of the British army coincided with a remarkable social, political and technological change in human affairs. This wider social revolution affected all aspects of life, including the military. Perhaps the greatest advantage officers of Haig’s era had over those in Wellington’s time was simply that, unlike their predecessors, they had access to a professional education. The training available at the Royal Military College at Sandhurst (established in 1800) and the Staff College at Camberley (revived in 1857) was perhaps not ideal, but at least it was a schooling of sorts in their chosen profession; that in itself draws Haig closer to Montgomery’s era rather than Welling ton’s. Although the popular view of Haig is that he was little more than a snobbish and ignorant opponent of all such change, this innately conservative man proved himself remarkably flexible in using and getting others to use new technology, once he was convinced it offered greater chance of success on the battlefield.

Haig was an ardent and lifelong believer in the virtues of the British empire, regarding it, as Lytton Strachey put it, as ‘a faith as well as a business’; he would have shared Strachey’s conviction that the monarchy was ‘a symbol of England’s might, of England’s worth, of England’s extraordinary and mysterious destiny.’1 Haig’s unquestioning devotion to the British monarchy and the empire it crowned seems today anachronistic; yet to understand Haig requires a comprehension of this. While Haig never questioned the sovereignty of Parliament, he early acquired an unwavering contempt for politics and politicians. They were, for him, ephemeral; apart from God, with whom Haig enjoyed almost the same taciturn relationship as he did with his fellow humans, only the monarchy was eternal and beyond questioning.

In the popular imagination today Haig enjoys low esteem. Few associate him with the Scotch whisky, whose famous slogan went ‘Don’t be vague, ask for Haig’, although he was a son of the founder of John Haig & Sons Distillers.2 If he is remembered at all, he is fixed in our minds as an incompetent Great War general, yet that conflict occupied only a fraction of Haig’s total military service. His dedicated professionalism preceding the Great War and his unpaid devotion to the welfare of ex-servicemen afterwards are both now largely forgotten. The argument that Haig can no longer be casually written off as a nincompoop has been advanced in a small but growing range of more thoughtful studies of the Great War, yet he is still seen as a sort of cack-handed butcher, the result largely of the prevailing view of the Great War as one vast, awful mistake.3 As Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) in Belgium and France between mid-December 1915 and the Armistice of 11 November 1918, a war in which almost nine and a half million men from the British empire enlisted in the armed forces and 947,023 died,4 Haig stood at the peak of a vast termite-like social, military and technological organization, with almost two million men under his overall command. The complexity of administering the BEF was such that Haig’s position was that of primus inter pares amon...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Contents