![]()

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

LIST OF MAPS

INTRODUCTION

1 WHERE IT ALL BEGAN

2 STATING THE CLAIM

3 FROM OBLIGATION TO PROFESSION

4 CRÉCY

5 TRIUMPH AND DISASTER – CALAIS AND THE BLACK DEATH

6 THE CAPTURE OF A KING

7 THE FRENCH REVIVAL

8 REVOLTS AND RETRIBUTION

9 ONCE MORE UNTO THE BREACH...

10 THE PRIDE AND THE FALL

EPILOGUE

NOTES

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

NOTE ON THE AUTHOR

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

INDEX

![]()

ILLUSTRATIONS

The Royal Coat of Arms (Public domain)

Battle of Sluys, 24 June 1340, from Froissart’s Chronicle (© Illustrated London News Ltd/Mary Evans Picture Library)

Sir Thomas Cawne (© Imogen Corrigan)

Battle of Crécy, 24 August 1346, from Froissart’s Chronicle (© Mary Evans Picture Library)

‘Blind’ King John of Bohemia (© Imogen Corrigan)

Edward the Black Prince (© Dean and Chapter of Canterbury Cathedral)

Sir John Hawkwood by Paolo Uccello (© Alinari Archive/Corbis)

Henry IV (© Imogen Corrigan)

Henry V by unknown artist, late 16th or early 17th century (© National Portrait Gallery, London)

Bertrand du Guesclin (© Imogen Corrigan)

![]()

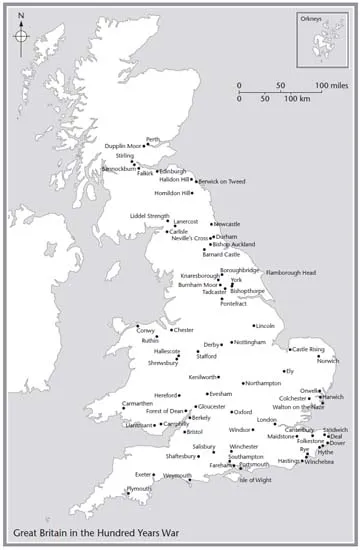

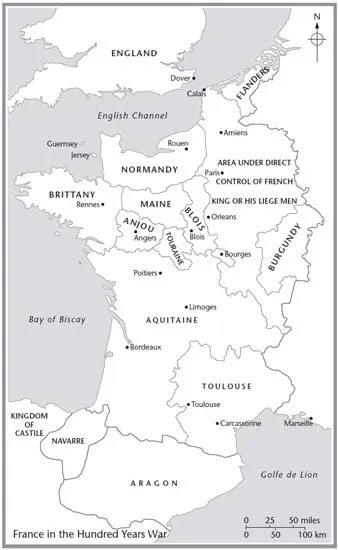

MAPS

Great Britain in the Hundred Years War

France in the Hundred Years War

Area of Operations: Flanders, 1337–40

Area of Operations: The Crécy Campaign, 1346

The Battle of Crécy, 23 August 1346

Area of Operations: The Black Prince’s Chevauchée, 1355

Area of Operations: The Poitiers Campaign, 1356

The Battle of Poitiers, 19 September 1356

Brittany in the Hundred Years War

Area of Operations: The Black Prince’s Spanish Campaign, 1367

Area of Operations: The Azincourt Campaign, 1415

The Battle of Azincourt, 25 October 1415

Area of Operations: 1416–52, Map 1

Area of Operations: 1416–52, Map 2

Area of Operations: 1416–52, Map 3

![]()

![]()

![]()

INTRODUCTION

In 1801, George III, by the Grace of God king of Great Britain, France and Ireland, dropped the English claim to the throne of France. For 460 years, since the time of the great king Edward III, all nineteen of German George’s predecessors had borne the fleur-de-lys of France on the royal coat of arms along with the lions (or leopards1) of England and latterly the lion of Scotland and the Irish harp. The withdrawal of the claim, which had been prosecuted with varying degrees of enthusiasm, was purely pragmatic: France and England had been at war since 1793, and, if England opposed the French Republic and supported a restoration of the Bourbon monarchy, then she could not also claim the throne for herself. A year later, in the Treaty of Amiens, which ushered in a short break in the war with France, England recognized the French Republic, and in so doing negated her own claims. It was the end, at least in theory, of England’s, and then Britain’s, claim to be a European power by right of inheritance.

It was not, of course, the end of Anglo-French rivalry. For two great powers occupying opposite sides of a narrow sea, both looking outwards, both concerned with trade and trade routes, and both with imperial ambitions will inevitably clash. And if in the twenty-first century that rivalry is concerned more with the interpretation of regulations emanating from the European Union rather than the ownership of sugar islands, and if the weapons are words rather than swords and gunpowder, the inescapable fact is that on average England and then Britain has spent one year in every five since the Norman Conquest at war with France. One can, of course, twist statistics to suit one’s purpose, but the alliances with France in both the Crimean War and the First World War, pre-Vichy France’s brief participation in the Second World War, de Gaulle’s Free French activities, and more recent French participation in NATO operations are very much the exception, and many old soldiers cannot forget that the armed forces of Vichy France fought British troops in the Middle East, Madagascar and North Africa between 1940 and 1943. The relationship between the Common Agricultural Policy and Crécy is not as distant as might appear, and some of the effects of that centuries-old enmity are with us still: when president of France, General Charles de Gaulle had a standing order that while travelling around the country he was never to be within thirty kilometres of Agincourt.

While the English claim to the French throne was the major cause of what came to be called the Hundred Years War, there were other factors too: the sovereignty of parts of France that had become English by inheritance, the annoying habit of the Scots to ally themselves with France, and English mercantile activities and ambitions in Flanders. It was not, of course, a sustained period of fighting, nor was it called the Hundred Years War at the time or for many years afterwards. Rather, it was a series of campaigns punctuated by truces, some of them lasting many years. And if we take the beginning of the war as Edward III’s claim to the French throne in 1337, and its end as the withdrawal of all English troops from Europe except for Calais in 1453, then it lasted for rather more than a hundred years. No one who stood on the docks at Orwell and cheered as the soldiers of the first English expeditionary force of the war sailed for France under Edward III was alive to welcome the men returning from the last campaign, and anyone living at the end of the war who could remember the great battle of Agincourt would have been well into middle age. The period might more accurately be described as the series of events which transformed the English from being Anglo-French into pure Anglo. But in as much as the causes of the war and the English war aims remained more or less constant, even if alliances did not, it is reasonable – and convenient – to consider the series of struggles as one war.

It was a good time to be a soldier. If a billet under Edward III or Henry V or commanders such as Bedford or Talbot was not available because of yet another truce, then there were always the Wars of the Breton Succession, where experienced soldiers could be sure of employment. And if a warmer or more exotic clime was an attraction, then the armies of John of Gaunt and the Black Prince campaigning in Spain were always looking for good men. It was not, however, a good time to be a civilian, or at least a civilian in what is now northern France. Ever-increasing taxation to pay for the war; conscription into the armies; marauding soldiery trampling over crops; looting and plundering; atrocities by both sides; the deflowering of daughters and the commandeering of food and wine: all combined to ensure that the lot of the European commoner was not a happy one. No sooner had the rural population recovered from one period of hostilities than the whole dreadful cycle would be repeated all over again. Disease stalked medieval armies, and, if dysentery or typhus spread by the movement of troops did not bring down the hapless peasant, then a visit from the plague probably would.

The Hundred Years War was hugely significant in the political and military development of Europe, of Britain and of France. Politically, it implanted the notion of a French national identity that replaced more local loyalties – and in this sense one could argue that, for all the destruction and devastation, France came out of the war in a far better state than she entered it. The war reinforced English identity and implanted a dislike and suspicion of foreigners that have not yet entirely gone from our national psyche. Militarily, it saw a real revolution in the way of waging war, initially in England and then, belatedly and partially, in France. In England came the growth of military professionalism, with the beginnings of all the consequences that flow from having a professional – and thus expensive – army; the rejection of war as a form of knightly combat in favour of deploying trained foot-soldiers supported by a missile weapon; and the beginnings of military law and a command structure that depended more on ability than on noble birth.

To most of us, the war means three great battles – Crécy, Poitiers and Agincourt – and some of the finest prose in the English language, put into the mouth of Henry V by Shakespeare. And while Henry may not actually have said, ‘Once more unto the breach, dear friends...’ he will have said something, like any commander on the eve of battle, and his 1415 campaign is a study in leadership that is still relevant today. But the war was far more than three battles, and in the latter stages the English were pushed back and eventually, with the exception of Calais, abandoned Europe altogether. While the withdrawal of English troops by 1453 was as much to do with a shortage of money and political instability at home as it was with military factors, winning battles without the numbers to hold the ground thus captured could not guarantee success, and this too is a lesson as relevant now as it was then.

In this book I have tried to stick to what I know best and to look at the war from the military perspective. But no subclass of history can stand alone – social, political, economic and military history all impinge upon each other – and it is impossible to comprehend why things happened, as opposed to what happened, without understanding the way people lived at the time: their ambitions, their lifestyles and their beliefs, and the motivating factors of religion on the one hand and acquisitive greed on the other. While some medieval kings might have planned for the long term, the vast bulk of their subjects could think only of the immediate future, at least in this world: for the farmer was but one visitation of murrain from ruination, the magnate or pauper one flea jump from the Black Death.

Historians must, of course, present both sides of the argument, but they do not have to be neutral. I hope that I have treated the facts, as far as they can be determined with accuracy, as sacred, but I cannot hide my conviction that England’s demands on France were lawful and justified, and, even where they were not, I feel pride in the achievements of Edward III, the Black Prince and Henry V. For all the cruelty and bloodthirstiness exhibited by many English soldiers of the time, I would far rather have marched with Henry V, Calveley, Knollys, Dagworth et al than with Bertrand du Guesclin, the best-known French commander, or Joan of Arc.

Sources for the period exist in great number, but not all are reliable, often being after-the-event propaganda, an exercise in post hoc ergo propter hoc logic (or lack of it) or, particularly in tapestry and painting, fanciful flights of the imagination. Battle paintings are many, some painted not long after the event, but they are sanitized and stylized, not the trampled and horse manure-covered fields of blood, gore, agony, sweat and death of unwashed, unhealthy men that a medieval battlefield must have been. Instead, we see nice neat lines of opposing soldiers, armour all brightly polished, everyone shaved, horses beautifully groomed, and always the sun shining against an impossibly blue sky. It cannot have been like that.

Whatever their limitations, original sources have to be considered, partly because their authors were there or talked to people who were there, so at least some of what they describe will have a grain, or more, of truth in it, and partly because, even if not historically accurate, they at least reflect what some people thought at the time. Jean Froissart is generally accepted as being one of the best contemporary sources for the early part of the war. A contemporary of Chaucer, Froissart was born in Valenciennes and was a minor official in the court of Edward III’s queen and also in that of Richard II. He was born around 1337, so his account of the preparations for and conduct of the Crécy campaign can only have been hearsay, but for all that he did approach the happenings of his time in a manner that would stand up to at least a cursory assessment of his methodology today. He had an inside seat for much of what he describes, he interviewed people who were present where he was absent, he contrasted differing reports, and he gives due credit to...