![]()

Part I

Foundations

![]()

1

Environmental Aesthetics and Art

I.TAKING AESTHETICS SERIOUSLY

The cover of my book features John Kane’s painting The Monongahela River Valley, Pennsylvania, composed in 1931. It’s one of several of his depictions of the surging industrialisation he encountered that evokes contrasting imagery of environmental change. An American folk artist, Kane celebrated the march of progress in a landscape teeming with activity that he personally laboured in: railroad trains, a steamboat and, most prominently in this painting, the billowing smokestacks of the behemoth steel mills sprawled along the Pittsburgh river valley. Yet this industrial topography competes with a bucolic landscape in the background, with gentle hills dotted with trees and cottages, which Kane admired equally. When asked of his interest in this subject, Kane replied, ‘because I find beauty everywhere in Pittsburgh’.1 Many environmentalists would disagree however, preferring the aesthetic of less adulterated nature to that bearing the imprint of human activity.

Public campaigns to save forests, rivers and other natural wonders often emphasise their aesthetic virtues, a concept relating to human sensory perceptions that I will later in this chapter define more clearly. Natural beauty has been the touchstone of this aesthetic value. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) affirms in its founding 1948 Statute that: ‘natural beauty is one of the sources of inspiration of spiritual life, and the necessary framework for the needs of recreation’.2 In 1962, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) echoed similar sentiments in declaring nature’s aesthetic values ‘a powerful, physical, moral and spiritual regenerating influence’.3 These sentiments also inhabit legal philosophy. John Finnis, a defender of natural law, enumerated seven basic goods that bring value to human lives that he believed the law should protect, one being aesthetic experiences.4

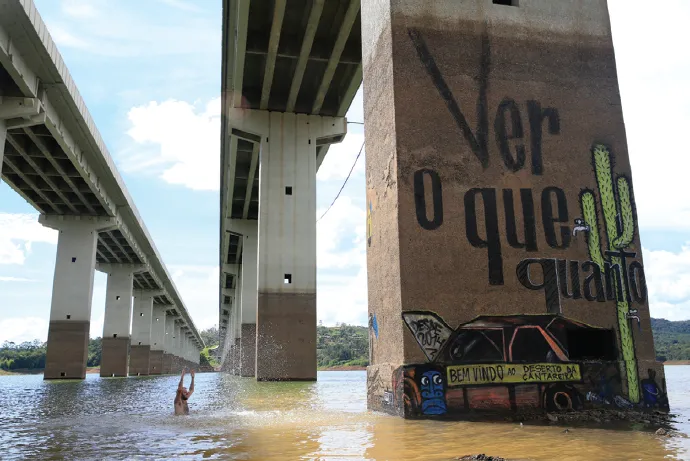

The appeal to aesthetics permeates the history of environmental politics and governance. The inauguration of the world’s first national park,5 at Yellowstone in the United States (US), was aided by the artists Thomas Moran, Frank Hayes and William Henry Jackson, whose portrayals of its grandeur through their photography and paintings helped convince Congress in 1872 to preserve the deep, glacier-carved valleys and mountains for posterity. The aesthetic disfigurement of nature has also galvanised action, such as the famous ‘Keep America Beautiful’ anti-littering campaigns.6 The arts have helped publicise ugly aesthetics, such as the mining and industrial scars revealed graphically by Canadian photographer Edward Burtynsky. The aesthetics of human suffering connected to environmental adversity can also seize attention. In the Brazilian city of São Paulo a severe water crisis intensified in 2015, exacerbated by a drought and the failure of municipal authorities to take preventive measures. The suffering communities collaborated with artists to express their grievances, painting colourful murals around the city, such as images of drought-related themes and ripostes questioning government policy, such as the example in Figure 1.1 on the legs of a bridge spanning São Paulo’s principal water source.7

Figure 1.1 São Paulo mural by Thiago Mundano, 2015; photograph by Frederick Bernas

Occasionally the law formally and explicitly acknowledges some of these aesthetic issues or concerns. The United Kingdom’s (UK) National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949 serves ‘the purpose of conserving and enhancing the natural beauty’,8 and British law now provides for designating ‘Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty’.9 International law has also embraced this agenda to some extent. The World Heritage Convention 1972 serves to safeguard ‘areas of outstanding universal value from the point of view of […] natural beauty’, such as China’s Danxia geological wonders and Australia’s Great Barrier Reef.10 Much environmental law however, as we will later learn, is insouciant about this realm, despite the influence of aesthetic appreciation on our environmental values and behaviour.

My book is devoted to showing how insights from aesthetics can enrich the study and understanding of environmental law. Aesthetics, be they relating to pictorial, musical or other art forms, can provide insights into environmental law that conventional modes of inquiry have relegated to the periphery. In arguing for aesthetics to be taken seriously, my book also highlights some problems associated with the aesthetic dimensions of environmental law. It is not enough simply to argue for the pertinence of aesthetic inquiry to environmental regulation and policy; we should also consider how aesthetics could improve governance and quell environmental risks.

Of the problems for environmental law that may come with aesthetics, one is that while aesthetic appreciation can gratify human sensory needs, it may lack intrinsic connection to the well-being of other species or the biosphere at large. It is naive to assume that what people find beautiful, they protect. As Kane’s painting shows, individuals’ aesthetic tastes can deviate from acceptable pollution control or nature conservation. Some may enjoy the look of industrial or urbanised landscapes despite their diminished biodiversity. Aesthetic tastes can also directly drive the destructive refashioning of nature to make it more appealing, for instance via introducing attractive but harmful exotic species. And even where authorities prioritise nature’s beauty for protection, it may skew societal attention to the most aesthetically spectacular – the Yellowstones of the world – while neglecting the aesthetically mundane but possibly ecologically significant biomes.

Aesthetic preferences are complex and open to diverse interpretation both within and between cultures. At stake is more than the colloquial refrain that ‘beauty is in the eye of the beholder’. Disputes over mining, forestry and other environmentally burdensome activity where aesthetic values are at stake can rarely be divorced from their social context. For working class labourers, a polluting factory provides a source of employment and companionship (as reflected in Kane’s experience) while for the affluent and educated such places invite disdain. Even among avowed environmentalists, aesthetics can etch sharp divisions: wind turbines are welcomed by many for combatting climate change but can arouse opposition if such ‘ugly’ facilities inhabit their own locales. These differences can enfeeble the law’s efforts to forge consistent and predictable methods of governing environmental activities.

Differences in aesthetic appreciation also shift over time, as Kane’s painting of ebullient industrialisation should suggest from our vantage, further challenging the normative strength of so-called ‘timeless’ aesthetic values. To indulge this point for a moment, consider the shifting sentiments about the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus), the arboreal marsupial now beloved as one of Australia’s premier tourist ambassadors. Until the early twentieth century it was slaughtered wholesale, especially in Queensland (illustrating also how nature’s aesthetic qualities such as animal furs can directly drive destructive practices). Then, in 1919, Norman Lindsay published his picaresque children’s tale, The Magic Pudding: Being the Adventures of Bunyip Bluegum and his Friends Bill Barnacle and Sam Sawnoff. The principal character in his bestseller was Bunyip Bluegum, a koala, who helped endear the creature to the public and contributed to its improved legal standing. An anthropomorphic koala called Blinky Bill was also the protagonist in the Australian illustrated children’s books authored by Dorothy Wall in the 1930s (see Figure 1.2).11 The Adventures of Blinky Bill, depicted in colourful, cartoon-like illustrations, evoked similar endearment. The tide began to turn: Queensland’s Fauna Protection Act 1937 gave permanent protection to the koala and later, in 1971, the species became Queensland’s official animal emblem ‘after a newspaper poll showed strong public support for this endearing marsupial’.12

Figure 1.2 Cover of Dorothy Wall’s Blinky Bill (Angus and Robertson, 1939)

Taking aesthetics seriously also involves determining how to reconcile aesthetic and non-aesthetic considerations in environmental governance. Scientific and economic criteria more commonly substantiate environmental rules and standards. Scientific knowledge injects supposedly objective and consistent criteria for decisions, as evident in procedures for environmental assessments of development proposals, setting pollution standards and managing endangered species, among many applications. Science offers additional rationales for action, such as that the natural environment offers life-supporting services including clean air, water and fertile soil, and it underpins technological innovations to mitigate our impacts, such as through solar and wind power. Economics comes into play too in numerous ways, such as cost-benefit analyses of proposed environmental policies, quantification of the economic benefits of ecosystem services, and financial incentives including carbon taxes to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. In these domains, policy-makers assume individuals to be sufficiently rational and self-interested to understand and respond appropriately to improved information and clearer incentives, while the ‘subjective’ and ‘superficial’ emotional values seemingly associated with aesthetics get marginalised from environmental governance.

While the natural sciences and economic incentives have undoubtedly often reshaped modern environmental law for the better, they lack a complete solution. The shortcomings of environmental law generally do not occupy my book, with much already written about them.13 Less well acknowledged is that our failure to manage the environment wisely stems more often not from lack of knowledge, but from lack of affection and altruism – values that aesthet...