![]()

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

Note on the text

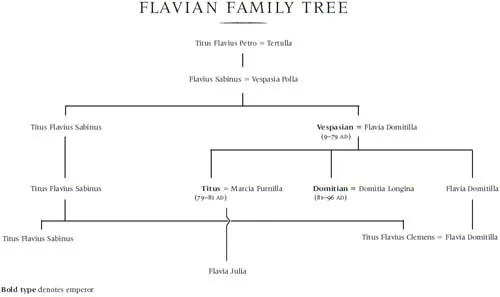

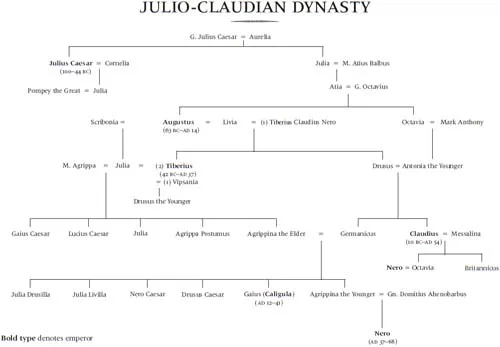

Family Trees

Introduction

I Julius Caesar: ‘Too great for mortal man’

II Augustus: ‘All clap your hands’

III Tiberius: ‘Ever dark and mysterious’

IV Gaius Caligula: ‘Equally furious against men and against the gods’

V Claudius: ‘Remarkable freak of fortune’

VI Nero: ‘An angler in the lake of darkness’

VII Galba: ‘Equal to empire had he never been emperor’

VIII Otho: ‘If I was worthy to be Roman emperor...’

IX Vitellius: ‘A series of carousals and revels’

X Vespasian: ‘The fox changes his fur, but not his nature’

XI Titus: ‘The delight and darling of the human race’

XII Domitian: ‘But the third’?

Bibliography

Notes

Glossary

Index

![]()

List of Illustrations

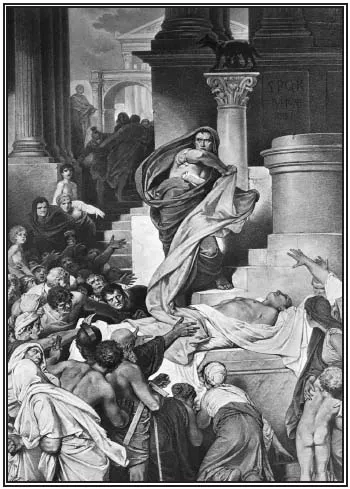

Introduction: Death of Julius Caesar by Alexander Zick © Bettmann / Corbis

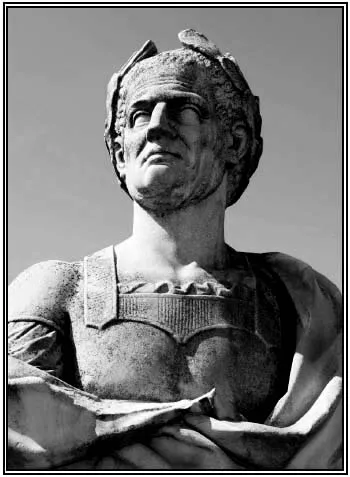

Julius Caesar: Statue of Caesar © Osa

Augustus: Bronze statue of emperor Caesar Augustus © Only Fabrizio

Tiberius: Statue of Tiberius © Toni Sanchez Poy

Gaius Caligula: Gaius Caligula, Emperor of Rome by Antonius © Stapleton Collection / Corbis

Claudius: 18th Century Engraving of Claudius © Chris Hellier / Corbis

Nero: Marble head of Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus © Lagui

Galba: Servius Sulpicius Galba Roman emperor, murdered by Otho, Mary Evans Picture Library

Otho: Marcus Salvius Otho Roman emperor, Mary Evans Picture Library

Vitellius: Male bust representing the emperor Vitellius © Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikipedia Commons

Vespasian: Titus Sabinus Vespasianus, Roman emperor, Mary Evans Picture Library

Titus: 19th century engraving of the Roman Emperor Titus, iStockphoto

Domitian: Ancient bronze Roman coin Domitian © Paul Picone

![]()

Note on the text

In the interests of readability and accessibility, I have tried wherever possible to restrict footnotes to a minimum. To this end, I have not provided specific notes on quotations from Suetonius’ Lives of the Caesars: the present account simply contains too many. All unattributed quotations therefore are from Suetonius. In each instance, I have made use of the translation by J.C. Rolfe first published in London by William Heinemann in 1914 – still, almost a century later, distinguished by its combination of accuracy, elegance and charm.

![]()

![]()

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Introduction: Death of Julius Caesar by Alexander Zick © Bettmann / Corbis

![]()

‘Exactitude is not truth,’ wrote the painter Henri Matisse in 1947. Readers of the Roman historian Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus must surely agree. In his De vita Caesarum – usually called in English The Lives of the Caesars or The Twelve Caesars – which was probably published in the decade after the accession of the emperor Hadrian in AD 117, Suetonius sought instances of both: not all overlap. Exactitude is apparently one result of much of his careful fact-finding and evidence-sifting; many of his truths are verifiable by reference to other surviving primary sources. Equally obviously, there are omissions from the twelve Lives; there are also areas where the reader must exercise caution.

In intent Suetonius’ approach to biography is comprehensive, embracing both the public and private lives of his subjects, and he essays impartiality, quoting conflicting opinions, demonstrating consistently that arguments have at least two sides, abiding by Virginia Woolf’s injunction that the biographer ‘be prepared to admit contradictory versions of the same face’.1 The principal property of his writing is not precision save in the sharpness and bold outline of the many anecdotes he preserves: he adopts (when it suits him) a loose chronology or schematic approach to his material, and his method intermittently suggests a squirrel hoarding nuts, piling and compiling details. He is not writing history as the ancients understood it – an account of the public and political life of the state in war and in peace: chronological, annalistic, thematic, interpretative. His work is life-writing, then as now accorded lowlier status, susceptible to intrusions of the subjective and admitting the possibility of alternative truths: a bravura unmasking of the office-holder behind the office. Given the open-handedness of his approach, his refusal either to endorse or to condemn, the cumulative effect of Suetonius’ research retains an exhilarating, mobile quality reminiscent of Impressionist and Pointillist paintings: an emphasis on looking and seeing; a manipulation of light and shadow; passages of bold colour; a vigorous quest for truth; a certain deliberate liveliness unconstrained by academic convention.

In a survey of female biography written at the turn of the nineteenth century, Mary Hays wrote: ‘The characteristic of the Roman nation was grandeur: its virtues, its vices, its prosperity, its misfortunes, its glory, its infamy, its rise and fall were alike great.’2 It was a statement of its time, a reiteration of that grandiloquence which history painters of the later eighteenth century had sought to extract from Roman subjects. But successive generations of readers have agreed with Hays’ vision of Rome, and it is possible to enjoy Suetonius’ biographies as the expression of this ‘grandeur’ coloured by a dozen different prisms, a compendium of glory and infamy, virtue and (notably) vice.

No account of Rome’s twelve rulers from Julius Caesar to Domitian can escape the long shadow of Suetonius. To attempt to do so would be contrary: that has not been my intention. The present work revisits Suetonius’ 1,900-year-old survey in acknowledgement of the immense riches both of its subject matter and of the author’s treatment. I have not attempted to imitate my starting point, which would not be possible, nor to offer a commentary on it, an academic appreciation or a riposte. Rather the present work, like Suetonius’, looks at the breadth of its subjects’ lives in an effort to uncover the human face of eminence and snapshots of vanished moments which are utterly remote from our own experience but intermittently familiar. Only implicitly does it address Lord Acton’s famous assessment of the connections between access to power and personal corruption which are all too evident in several Caesars’ spectacular failings.

Instead, the present Twelve Caesars, informed by additional primary sources and associated secondary material including paintings, revisits aspects of that earlier magnum opus in an effort to create for the generalist reader portraits which recall telling facets of twelve remarkable men: the political seen through the personal, the private impulse exposed to public scrutiny, even the history of their histories, which expresses another kind of truth. None of these portraits is exhaustive; none is encyclopedic. None aims primarily to titillate, none to instruct or offer moral exempla. Material is arranged by turns thematically and chronologically, a loosely knit garment, the intention to cast light on the origins, nature and impact of lives and careers which cannot otherwise be satisfactorily confined within a book of this length. Each of these vignettes, I hope, explores ‘the creative fact; the fertile fact; the fact that suggests and engenders’.3 The present work is an entertainment, and will have succeeded in its aim if a single reader is inspired to return to that earlier, justly celebrated Twelve Caesars.

![]()

JULIUS CAESAR

(100–44 BC)

‘Too great for mortal man’

Julius Caesar: Statue of Caesar © Osa

![]()

Isolated by eminence, ‘the bald whoremonger’ Gaius Julius Caesar conceals from us the innermost workings of heart and mind. ’Twas ever thus. Repeatedly he came, saw, conquered; he wrote too, and with impassioned gestures and in a high-pitched voice he importuned his contemporaries if not for love, then for acquiescence, assistance, acknowledgement, awe, acclaim, an approximation of ardour and, above all, admiration and action. He did not stoop to explanations, but asserted unblushingly that dearer to him than life itself was that public renown the Romans called dignitas (a quality he rated higher than moral decency, according to Cicero).1

The scale of his achievements dazzled and repelled his contemporaries. (So too a habit of playing fast and loose with the strict legalities of those offices of state he won by bribery, force of will and sheer charisma.) Ancient sources, including Cicero’s letters, betray this ambivalence: they omit to unravel any motive bar vaunting self-belief. Openly Caesar regarded himself as the leading man of the state. He could tolerate no superior and once announced that he preferred the prospect of pre-eminence in a mountain backwater to second place in Rome. Suetonius claims that he ‘allowed honours to be bestowed on him which were too great for mortal man... There were no honours which he did not receive with pleasure.’ We know too well the outcome.

Intermittently his character was cold, the white heat of ambition his defence against the loneliness of epic hubris. We learn as much of the man himself from the handful of portraits which survive from his own lifetime: long-nosed and broad-browed, with strong cheekbones, a resolute, direct gaze and the receding hairline which caused him such anguish. Their style has yet to evolve that bland idealization which will transform the public face of his successor Augustus from autocratic wunderkind to ageless marble dreamboat. As the written sources confirm, Caesar’s was not the appearance of a hero (nor was blandness among his characteristics). He dressed with eccentric flamboyance, customizing the purple-striped tunic that was the senator’s alternative to the toga with full-length fringed sleeves and a belt slung loosely about his waist; later he affected scarlet leather boots. Fastidiousness bordering on vanity reputedly extended to depilation of his pubic hair. It is the sort of detail by which the Romans habitually found out their heroes’ feet of clay and we may choose to disregard it if we will.

Of the twenty-three dagger wounds inflicted on Caesar on the Ides of March 44 BC by that conspiracy of friends, Romans and countrymen – not to mention cuckolded husbands and former colleagues – only one was fatal, poetically a wound to the heart (or near enough). It was not a poet’s death, although Caesar had written poetry – one composition, appropriately called ‘The Journey’, undertaken on the twenty-four-day march from Rome to Further Spain. Rather it was the death of a man who had sown and reaped mightily. As he announced at Marcus Lepidus’ dinner party while dissent fomented, his choice had always been for a speedy death. Conspiracy did not thwart that final ambition. Given his apparent disregard for the good opinion of Rome’s governing class, his destiny, as Plutarch concluded, was ‘not so much unexpected as... unavoidable’.2

Compulsively adulterous, subject to the aphrodisiac of power as he resisted submission in every other aspect of his life, he cultivated a legend of personal distinction and vaulting audacity in which none believed more fully than he. At a time when unbridled self-esteem was inculcated in the majority of senators’ sons, Caesar succumbed in splendid fashion.3 He dreamed, a soothsayer explained to him, that he was destined to rule the world: a restless spirit, unchecked energy and an irrational need for paramountcy drove him towards that preposterous goal. ‘Caesar’s many successes,’ Plutarch wrote, ‘did not divert his natural spirit of enterprise and ambition to the enjoyment of what he had laboriously achieved, but served as fuel and incentive for future achievements, and begat in him plans for future deeds, and a passion for fresh glory, as though he had used up what he already had.’4 Those achievements were to change the political map of Europe and divert the course of Western history, connec...