![]()

1 Introduction: A New Maximalism

maximalism noun: an aesthetic or philosophy that prizes multiplicity

Maximalism in fashion refers to the new turn in fashion toward the mixing of numerous, seemingly incongruous prints in the same ensemble, but the sheer variety of new methods ushered in by our use of digital technologies has led to what I call a new maximalism in research practices. Mixed-methods approaches using multiple digital sites and strategies have been the norm for some time in the social sciences, but fashion history is catching up. The year that I began writing this book, 2016, was a year of maximalism in the word of fashion.1 Whereas just a few years ago, brands like Céline were being touted for their clean, restrained touch, in 2016, it was suddenly acceptable and even desirable to mix prints beyond the point of clashing. Coco Chanel’s old adage that a person should take off one accessory before going out went straight out the window; now, it is put two extra rings on before going out. Alessandro Michelle’s reinvigoration of luxury fashion house Gucci typifies this new maximalism, mixing colors and textures, fabrics and prints. Dolce & Gabbana have also adopted the maximalist aesthetic, even creating odd wearable technology meets glamor juxtapositions by adding headphones to tiaras. Enormous and elaborate handbag charms that do not coordinate with the rest of the bag seem to be the newest iteration of maximalism.

Maximalism is certainly fun, but is it also merely frivolous, or is there some deeper philosophy undergirding all the prints and tiaras and handbag charms? Legendary Bauhaus turned American architect and Illinois Institute of Technology professor Ludwig Mies van der Rohe famously uttered the maxim: “Less is more.” While that may have been true for International Style architecture in the 1950s and ’60s—those steel and glass boxes totally devoid of ornament, today in architecture as in the fashion world, more is more. Or, as one of the postmodern starchitects,2 Robert Venturi put it, “Less is a bore.” In fashion, the new “more is more” aesthetic has taken on the moniker of “maximalism” (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Maximalist runway show fashion photograph, Pexels.com.

About this Book

In English, we use “fashion,” “dress,” and “costume” to describe the clothing that people wear, fashion in particular referring to the endless succession and repetition of the popular styles of the moment. But as Heike Jenss, editor of Fashion Studies (2016) notes, “In the Romance languages as well as in many Germanic languages, through interestingly not in English, the word for fashion is mode or moda derived from the Latin word modus for shape or manner, which is also a root of the word ‘modernity,’ associated with the fast-paced urban life in European capitals for which fashion (or la mode) became a symbol or metaphor” (see Baudelaire 2004).3 I would love to have titled this book Research à la Mode or something similar, as mode is linguistically more suggestive of a method or way of doing things than any of the English terms listed above. Many readers of this book undoubtedly not having a background in the Romance or Germanic languages, however, Research à la Mode sounds a bit too much like research with a side of ice cream, which would not necessarily be a bad thing in practice but is certainly not in keeping with the spirit of the book.

Thus, this volume is titled Digital Research Methods for Fashion and Textile Studies, and I have chosen to use the term “fashion” primarily in this book, rather than its sister terms “dress” and “costume.” I decided not to use costume, even though it is the preferred term for the field among academic historians in the United States, as evidenced by the name of their professional association, the Costume Society of America. But I find that whenever I mention “costume” to someone outside academia, they invariably think I am talking about theatrical costumes. So, for the sake of minimizing confusion, “costume” was not a good option or this project. “Dress” is the more frequently used term among academics in the UK, and as Jonathan Faiers noted in his essay “Dress Thinking: Disciplines and Interdisciplinarity,” dress is a more universal term, while “fashion” has implied in the past a more Western, elite mode of dress.4 Both the field of costume/dress/fashion studies and its terminology are changing, however. Globalism in the apparel and textile complex, the closing of university home economics departments, and the recognition of designing clothing as an art and not just a craft have all contributed to the increase in the preference for the term “fashion,” even among academic historians of the subject, as seen in recent titles such as Harriet Walker’s Less Is More: Minimalism in Fashion (2011). And of course, as a practical matter, many readers of this book are undoubtedly graduates of or students in fashion (rather than “costume” or “dress”) courses of study.

Costume. Dress. Craft. Art. Home economics. History. Fashion studies in the early twenty-first century, like an Alessandro Michelle ensemble, is an idiosyncratic object, made of many components some of which—like art and craft—seem diametrically opposed to each other, and yet which function as a harmonious, albeit complex, and at times cacophonous, whole. This book takes maximalism as a metaphor for mixed-methods research, as well as for multi-theory hermeneutic critical reading (see Chapter 4), but maximalism also serves as a metaphor for fashion as an academic discipline. To extend the metaphor further, our field is not the clean, pared down minimalism of the university art department, nor the practical street wear of the school of home economics or human ecology, but rather a combination of the two in the same outfit—the paint-splattered khaki all-in-one with a floral print day dress worn over it.

Just as the discipline of fashion studies combines ideas and practices from a variety of related fields, so too does fashion studies rely on a mixed bag of research methodologies. This is increasingly true in the digital age. Digital Research Methods in Fashion and Textile Studies presents the reader with a variety of digital methodologies to aid in better searching for, analyzing, and discussing vintage design, photography, and writing on fashion, as well as historic and ethnographic dress and textile objects themselves. This book will help you to:

- Gain a familiarity with various digital research methods and explore through practical case studies how they can interface with work in fashion and textile studies.

- Learn how to incorporate digital methods to enliven and enrich a research project in progress.

- Benefit from simple changes that you can make to integrate digital activities into your day-to-day working life as a fashion researcher, such as joining new channels for scholarly communication and feedback from peers.

Each chapter focuses upon different methods, problems, or research sites, including:

- Searching large databases effectively

- Family history

- Pattern recognition and visual searching

- Mobile methods for communicating with other scholars digitally

- Maximalism and mixed-methods approaches to research

- Data visualization

- Mapping

- Critical reading of social media texts

Much like fashion itself, research methods are constantly evolving. In today’s rapidly changing climate, we are all beginners in some respects. Younger readers will likely be more familiar with many of the resources, but perhaps not with the methods. Established scholars will surely be more familiar with many of the methods, but possibly not with the new contexts engendered by the digital. From advanced undergraduate and postgraduate students working on research projects to veteran professionals in fashion and textile history and beyond, everyone can benefit from a diverse set of fresh approaches to conducting and disseminating research. In the current age of instant gratification, with users snapping and posting images from runway shows long before the clothes will ever appear in stores, the world of fashion is increasingly digital and fast-paced. Research on fashion is, too. Digital Research Methods will help you keep up.

Postmodernism and Positivism in Mixed-Methods Research

Dick Hebdige, in particular, has been a pioneering force in the mixing of qualitative methods and theories in fashion studies research. His 1979 book, Subculture: The Meaning of Style, uses semiotics, structuralism and post-structuralism, as well as draws upon Claude Lévi-Strauss’s concept of bricolage. With the digital turn in fashion and textile studies, however, scholars can now add quantitative methods into this mix as well. Further, as Heike Jenss notes:

The field of fashion studies in the United States (and beyond) now encompasses a substantial number of scholars who are located in academic programs that bring together social science approaches, economics, and the physical or natural sciences. These include for example, textile and apparel programs, which are located in university departments for human development, family and nutrition sciences, or in the departments for design, technology and management, marketing and merchandising, or consumer studies—fields in which quantitative studies are used frequently.5

On the escalation of interdisciplinarity and the need for mixed-methods research, Jenss writes:

Fashion and fashion studies’ wide reach and also its ‘in-between-ness’ (Granata 2012) makes for an exciting field of research, yet the ‘escalation of interdisciplinary research’ (Taylor 2013, 23) can also feel overwhelming, not least for students and emerging scholars, who are trying to find their footing in the field … the field’s dense disciplinary entanglements, which bring a wide range of methods to the field—and the essential need for the use, combination, and adaptation of multiple methods in the exploration of fashion.6

Kaiser and Green note that the International Textile and Apparel Association’s journal, the Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, has recently published several articles focused on causality in marketing using structural equation modeling (SEM) as a methodology.

Yet in the 2005 edition of their handbook, they [Denzin and Lincoln] described the “re-emergence” of “scientism” in the United States in the early years of the twenty-first century, promoted by the National Research Council’s call for objective, rigorously controlled studies that employed causal models (Denzin and Lincoln 2005, 8). Advanced statistical techniques such as structural equation modelling (SEM) have become fashionable in the context of consumer studies.7

But while the sub-discipline’s of fashion retailing and marketing are largely positivist in their research at present, the larger discipline (and indeed the case studies in this book), even while adopting and adapting some quantitative techniques, is still largely qualitative and a product of the postmodern turn of the 1980s.

Mixed-Methods Research as Maximalism

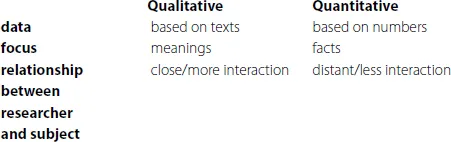

Sometimes called “messy methods,” mixed-methods research is fundamentally a form of assemblage, much like the maximalist impulse in fashion. In their introduction to Deleuze and Research Methodologies, Rebecca Coleman and Jessica Ringrose define assemblage as “a key concept that seeks to account for multiplicity and change (or becoming).”8 Coleman and Ringrose also construct method as a form of crafting, writing, “method is the crafting of the boundaries between what is present, what is manifestly absent, and what is Othered.”9 Assemblage and craft are apt metaphors for this type of research, and indeed in their book, Foundations of Multimethod Research: Synthesizing Styles, John Brewer and Albert Hunter note that metaphor is one technique for generating research problems that lends itself to mixed-methods work. They give examples such as “night as frontier,” “neighbourhood as fashion,” and “cities as organism.”10 In fact, the idea for this book is based on the metaphor of maximalism in fashion for mixed-methods research. No one set of methods—qualitative or quantitative—should be seen as inherently better than the other; nor are they philosophically irreconcilable. For example, in a research project, one could use both qualitative analysis of texts such as a film and fashion and textile objects themselves, along with raw objective spatial data taken from a mapping program (quantitative). This is the mixed-methods approach in a nutshell—using a variety of qualitative and quantitative techniques to answer your research question and tell a designer, wearer, or dress or textile object’s story. The following is a brief overview of the qualitative and the quantitative.11

Types of research methods include archival (historical, statistical), field work (ethnographic), and surveys and experiments. These basic methodologies can be mixed in one study in various ways, either concurrently or sequentially, for example: two forms of the research question, two types of data analysis (numerical vs. text-based or visual), or two types of conclusions (objective vs. subjective).

Carolyn S. Ridenour and Isador Newman call qualitative and quantitative a false dichotomy. “The research question initiates any research study. [I always ask my students: ‘What’s your thesis?’ ‘What are you trying to prove about the designer/garment/etc.?’] The research question is fundamental, much more fundamental than the paradigm (qualitative or quantitative) to which a researcher feels allegiance.”12 According to David E. Gray, one of the major benefits of mixing methods is “initiation,” which “uses mixed methods to uncover paradoxes, new perspectives, and contradictions. The focus of initiation, then, is the generation of new insights which may lead to the reframing of research questions, in the words of Rossman and Wilson: ‘a feeling of a creative leap.’”13 One of the ways to make that creative leap is to use narrative to tell your story. Narratives have ethical, political implications, causality, a sense of identity (of the narrator and of the characters). In Using Narrative in Social Research: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches, Jane Elliott unpacks an “existing debate about whether it is possible to integrate approaches that emphasize individuals’ subjective beliefs and experiences with approaches that provide a numerical description of the social world.”14 Add to this the additional layer of digital tools, and quantitative data can tell stories.

The following example is a story from my own research practice: I used qualitative methods to test my hypothesis of a connection—a single pattern or original, unique ima...