![]()

1

A childhood close to power

Sergei Uvarov was born on 26 August 1786 and later recalled Empress Catherine’s presence at his baptism. She was his godmother.1 His father was a vice-colonel (‘Vitse-Polkovnik’) among Catherine’s lifeguards: a handsome, carefree man who had risen on the coat-tails of a cousin’s military success. The diarist Filip Vigel’ thought of Semyon Fyodorovich Uvarov as ‘good, honorable, brave and merry’.2 He was charming and outstandingly musical, able to play the formidable Ukrainian bandura, with its sixty strings, and dance knees-bent, Cossack-style, holding the bulbous, long-necked instrument in one hand. The empress’s favourite prince, Potemkin, considered him an ideal courtier and nicknamed him ‘Sen’ka the bandura-player’, which is how everyone at court came to know him. Potemkin even encouraged Catherine to make Sen’ka’ on of her adjutants.3 But in truth Sen’ka was not at all well-connected. The Uvarov family had entered the tsar’s service in the fifteenth century and the name was honourable enough, but the latest representative had few resources in money or kind and no well-placed relatives.4 So, one might surmise, he relied on being an entertaining companion.

Sen’ka married Darya Ivanovna Golovin in 1784 when he was already forty, and she was said, according to the slanderous habit of the times, to be on the shelf. Darya brought with her a large dowry and on her paternal side an excellent heritage. The Golovins were one of the great aristocratic Russian clans, with their quality enhanced by many good connections made through marriage over the past century and a half of Romanov rule.5 Her older sister Natalya was married to Alexei Kurakin, a future minister of internal affairs. The family knew that Darya was marrying beneath her status, but everyone could see she was happy.6

After their wedding the Uvarovs set up home at the regimental headquarters next door to Catherine’s court, where they were waited on by junior ranks. Not long after Sergei was born, they had a grand house built on the newly granited banks of the Catherine canal in the centre of St Petersburg. By the beginning of 1788, Darya was pregnant again. However, the family was already in difficulty. Sen’ka had no talent for business, people said. While talented in music, in life he was unreliable. As soon as he was installed at court, his new importance went to his head. He lost his fear of Potemkin and ruined the company of which Catherine named him vice-colonel. According to that distinguished prince, after a stint under Uvarov all that was left of this highly disciplined unit ‘was its outward appearance, and the fact that the grenadiers could sing’.7 Whereupon, for reasons no one was able to determine, Sen’ka went missing in battle against the Swedes in Finland.8

Sergei was not yet even two and the new arrival, his brother Fyodor Semyonovich, was a babe in arms. Darya was left in great financial difficulty. Growing ill with worry, she turned to Alexander Mamonov, Catherine’s latest lover, to see if he couldn’t persuade the empress to pick up the colossal bill of 70,000 roubles for the house. When only five thousand were forthcoming, Darya had to abandon Dom 101 on the Catherine Canal.9 The family meanwhile was outraged. Why hadn’t she restrained her high-spending husband? Her parents, with evidently all their wealth tied up in land and serfs, the habitual aristocratic lament, were powerless to help. They wondered about their daughter’s character. It seemed that she too had been spending wildly.

Darya turned to her sisters in-law, the Kurakins, for help. That was the privilege Sergei ought to have highlighted in any autobiographical sketch. The Kurakin family invited their two nephews to grow up in their extended household, alongside nine vospitaniki: boys quasi-adopted for the sake of their education.10 The situation was not so unusual. The sons of the gentry were often brought up fatherless because of the demands of military service.11 The illegitimate and the orphaned were readily adopted.12 But Uvarov was exceptionally blessed by his adoptive family background. Like the Uvarovs the noble line of the Kurakin family went back to fifteenth-century Muscovy. Meanwhile, it owed its present high profile to the distinguished figure of Boris Ivanovich Kurakin (1676–1727). Close to Peter the Great as a government servant and as his brother-in-law, close associate and friend, Boris Kurakin had successfully negotiated the end of the Great Northern War which made Russia a modern European power. He had wit, brains and style, and in the remainder of his life he became Russia’s first permanent ambassador abroad in Paris. He was writing a book about his life and times when he died leaving behind seven children from two marriages. One of those seven, Alexander (1697–1749), succeeded him at the mission in France. In turn it was Alexander’s son Boris-Leontii Kurakin (1733–64) who became a senator and key economic adviser to Catherine II, and Boris-Leontii’s sons Alexander (b. 1752) and Alexei (b. 1759) who took the Uvarov brothers under their wing. Alexei Kurakin – a composer in his spare time, and a man passionate about theatre – was married to Darya’s sister Natalya.

Alexei, who was also an expert in banking and finance, took a stern view of Darya’a predicament and counselled her on ways of living economically. He suggested that she live outside the capital to reduce her costs and that she should not borrow any more money if she wished to spare the family further embarrassment. But Darya, energetic and headstrong, was a cultivated woman from the metropolis and the idea of moving to the country where life would have been dreary and ignorant and slow did not appeal. So she patched up the family’s existence in Piter, as the northern capital had long been affectionately known, and within a couple of years resumed her presence in society. She has been called ‘spoiled and unscrupulous’ and accused of conniving to have her sons educated in the Kurakin household,13 but in another age she may well have been looked upon as a survivor, for she seems to have been a sharp-witted, spirited woman determined to see her sons make good.

The Kurakin aspect of his education ought to have made Sergei Uvarov a liberal. His Kurakin uncles had a remarkable liberal education themselves, supervised by one of the best-known courtiers of Catherine’s reign, Nikita Ivanovich Panin.14 The empress had Panin, who was also head of her Ministry of Foreign Affairs, educate her son Paul after an attempt to secure the encyclopedist d’Alembert failed. The education Panin prescribed included statecraft, familiarity with the ways of the Orthodox church, and knowledge of classical French literature, language and ways. It allowed the idea that civil life – not yet in Russia, but perhaps one day soon – might be grounded on the basis of law. Uvarov, however, ended up being educated at home by a French abbé by the name of Mauguin who had fled the Revolution from his estate in Bordeaux. Mauguin seems to have been a modish choice on the part of his mother. (‘Don’t send me a Frenchman or a German. I want an abbé,’ declared the fashionable woman of the day.15 ) Darya sold two child serfs from her Yaroslavl estates to a female relative on her husband’s side of the family to help pay for Mauguin’s services.

Very quickly it was apparent Sergei Uvarov was a boy of peerless ability. He could write French with native fluency before his teens. He read La Bruyère on the corrupt, but nicely polished ways of the court of Louis XIV and some minor works of Voltaire. He would always love classical French literature, as much for its language as its content. Mauguin had him read travelogues too, classic versions of The Grand Tour. Radishchev had shown how politically devastating this educative form could be when turned on Russia itself. But Mauguin had Uvarov travel mentally in an earlier and quite different world. The Letters Sent to His Mother in 1764 From a Journey to Switzerland, by Stanislas de Boufflers, reflected the interests of the seigneur in women, horses, land, politics and idyllic landscapes. Boufflers, born in 1738, was the grandson of Maréchal Louis Francois de Boufflers, one of the most important men at the Sun King’s court and elected to the Académie française in 1788. Intelligent and well-travelled, the later Chevalier de Boufflers, like many subscribers to the moderate Enlightenment, accepted social inequality as a condition of political stability, and passed that view on to his young Russian reader.

As Uvarov studied, willingly and ably, Charles Mercier-Dupaty’s Lettres sur l’Italie en 1785 also imparted to him something of the history of art. Uvarov had a real connoisseur’s bent, and this education was not wasted on him. He later built on his knowledge to become an enthusiastic collector of the great neoclassical sculptor Canova. He loved neoclassical art as he loved neoclassical French literature.

But, again, where was Russia in all of this? Radishchev’s point about adapting Lawrence Sterne’s A Sentimental Journey to Russian conditions was to tell young men of Uvarov’s generation that the days for following the arts merely as a pastime in Russia were over. Social issues pressed too hard. Reform was desperately urgent. Still there’s no indication Uvarov ever read Radishchev. He grew up to have fine taste in matters that were artistic but morally superficial. Meanwhile, politically he had this great animus against revolution which the abbé Mauguin could only have endorsed.

When he entered public service in August 1801, twelve months earlier than the minimum age of sixteen, it was probably under the influence of Alexander Kurakin. A new tsar had come to the throne in March, and Kurakin had been made vice-chancellor. Some of his peers already found Sergei Uvarov too good to be true. Filip Vigel’, the principal diarist of the age mentioned earlier in this chapter, disliked him at first sight: ‘One rather handsome boy appeared to me to be entirely insupportable and annoying; he was presumptuous, arrogant, garrulous and, in a loud voice and without any humility whatsoever, deliberated about French literature and theatre.’16 Vigel’ and Uvarov worked alongside each other in the College of Foreign Affairs, soon to be renamed the Foreign Ministry, and went on studying while they worked. Vigel’ was homosexual and Uvarov would become a noted bisexual in ruling circles, so perhaps there was always that additional tension between them.

Sergei probably attended the Cadet School in Petersburg, an elite cramming-house run along the lines of a French lyceé, where the curriculum included French, English, German, Latin, Russian and fencing, while at the Ministry his work mainly involved translating.17

All the while he was being egged on by his mother, and it was about this time that he began to socialize in earnest in the circles close to the tsar. The Kurakins had enjoyed a close relationship with the previous ruler, Paul I, and after his death the dowager empress Maria Feodorovna became hostess of one of the most important salons of the decade. Darya encouraged her son to win the empress’s attention. Alexei Kurakin accused her of compromising her son with her pushiness, but the Uvarovs were undaunted. Sergei was under particular pressure to visit Marya Naryshkin, the tsar’s mistress, more often.18

The glory of the age, at least for the nobility that created and enjoyed it, was the Franco-Russian house party – lavish merrymaking continued at this party right up until 1917.19 Similar parties took place in this period in the cosmopolitan salons of Petersburg and in the cosier, more markedly Russian atmosphere of the Moscow houses. (Madame de Stael would find them to be ‘tartar material with a French border’ when she visited in 1812.)20 They underpinned the francophone high society that Leo Tolstoy, born in 1828, would portray to the next generations. This was the culture that was so memorably depicted as socializing its way to a complete unsuspected end in Alexander Sokurov’s film Russian Ark (2002). Uvarov loved the cultural conventions of this extraordinary class, and he shone there, with his talent for amateur dramatics, his ease in several languages and his eloquence about books. Alexei Kurakin had to concede that this Franco-Russian ‘Serge d’Ouvaroff’ was destined for the heights: ‘Ouvaroff will make his way. … You should know that of all the young men of his age he is the pearl, and not many like him are born.’21

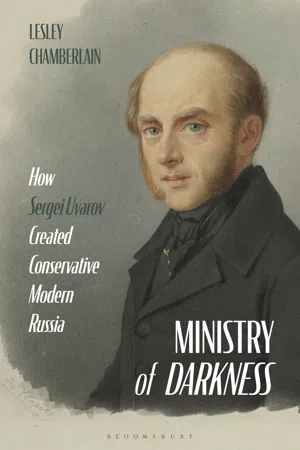

The St Petersburg salon of Alexei Nikolaevich Olenin and his wife was the gathering Uvarov singled out, and later he was at pains to say how Russian it was, in fact. Whatever critical thoughts people had in retrospect, he wrote fifty years later, the Olenin salon was peculiarly Russian and of immense value to th e nascent arts of the early nineteenth century. Olenin was at once a favourite of the court, a future director of the Imperial Public Library, a book illustrator and an archaeologist. When Uvarov first visited his home on the Fontanka Canal, he was ravished by Olenin’s collection of antiquities and dated his own interest in archaeology from that moment. ‘Art and literature found a modest but constant refuge in [his] house,’ he reminisced.22 This lively scene of Russian art, literature and learning stoked his patriotic pride from an early age. He wrote: ‘[Olenin’s] ardent love of everything which might lead to the development of Russian talent did much to ensure the success of Russian artists. Kiprensky was discovered and encouraged by him. … The two Bryulovs did not forget [his] constant support.’ Orest Kiprensky would one day paint Uvarov’s own portrait, while the (Huguenot) name of Karl Bryullov became famous, and all the more celebrated in Italy, with his spectacular oil painting The Last Days of Pompeii (1830–1833). The works of the fabulist Ivan Krylov were read among friends at the Olenin’s for the first time. Another important guest was Nikolai Gnedich, the Russian translator of Homer. The dramatist Vladislav Ozerov appeared one day with the manuscript of his play Oedipus in Athens (1804) and first rehearsals took place at the Olenins.

Uvarov’s claim that modern Russian culture was born in the salons was not wrong. Writers like the court poet Gavrila Derzhavin, Krylov the Russian Aesop, the Romantic poet Vassily Zhukovsky and, eventually, the poet Alexander Pushkin who was born in 1799, created it. It was literary art that barely touched the life of the ordinary Russian, and until Pushkin the literary language was removed from ordinary speech. But the salon atmosphere of Franco-Russia raised enough men of independent critical thought, with a great interest in a better Russia, to provide the first generation of the Russian i...