eBook - ePub

Killing Pablo

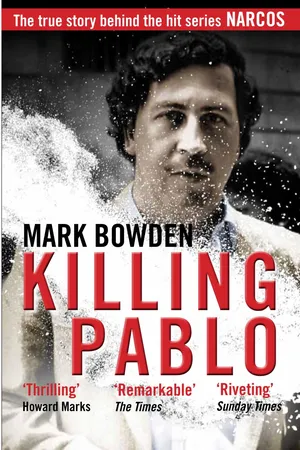

About this book

The bestselling blockbusting story of how American Special Forces hunted down and assassinated the head of the world's biggest cocaine cartel.

Killing Pablo charts the rise and spectacular fall of the Columbian drug lord, Pablo Escobar, the richest and most powerful criminal in history. The book exposes the massive illegal operation by covert US Special Forces and intelligence services to hunt down and assassinate Escobar. Killing Pablo combines the heart-stopping energy of a Tom Clancy techno-thriller and the stunning detail of award-winning investigative journalism. It is the most dramatic and detailed and account ever published of America's dirtiest clandestine war.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

THE RISE OF EL DOCTOR

THE FIRST WAR

IMPRISONMENT AND ESCAPE

LOS PEPES

THE KILL

AFTERMATH

Sources

Acknowledgments

Index

PROLOGUE

December 2, 1993

On the day that Pablo Escobar was killed, his mother, Hermilda, came to the place on foot. She had been ill earlier that day and was visiting a medical clinic when she heard the news. She fainted.

When she revived she came straight to Los Olivos, the neighborhood in south-central Medellín where the reporters on television and radio were saying it had happened. Crowds blocked the streets, so she had to stop the car and walk. Hermilda was stooped and walked stiffly, taking short steps, a tough old woman with gray hair and a bony, concave face and wide glasses that sat slightly askew on her long, straight nose, the same nose as her son’s. She wore a dress with a pale floral print, and even taking short steps she walked too fast for her daughter, who was fat. The younger woman struggled to keep pace.

Los Olivos consisted of blocks of irregular two- and three-story row houses with tiny yards and gardens in front, many with squat palm trees that barely reached the roofline. The crowds were held back by police at barricades. Some residents had climbed out on roofs for a better look. There were those who said it was definitely Don Pablo who had been killed and others who said no, the police had shot a man but it was not him, that he had escaped again. Many preferred to believe he had gotten away. Medellín was Pablo’s home. It was here he had made his billions and where his money had built big office buildings and apartment complexes, discos and restaurants, and it was here he had created housing for the poor, for people who had squatted in shacks of cardboard and plastic and tin and picked at refuse in the city’s garbage heaps with kerchiefs tied across their faces against the stench, looking for anything that could be cleaned up and sold. It was here he had built soccer fields with lights so workers could play at night, and where he had come out to ribbon cuttings and sometimes played in the games himself, already a legend, a chubby man with a mustache and a wide second chin who, everyone agreed, was still pretty fast on his feet. It was here that many believed the police would never catch him, could not catch him, even with their death squads and all their gringo dollars and spy planes and who knew what all else. It was here Pablo had hidden for sixteen months while they searched. He had moved from hideout to hideout among people who, if they recognized him, would never give him up, because it was a place where there were pictures of him in gilded frames on the walls, where prayers were said for him to have a long life and many children, and where (he also knew) those who did not pray for him feared him.

The old lady moved forward purposefully until she and her daughter were stopped by stern men in green uniforms.

“We are family. This is the mother of Pablo Escobar,” the daughter explained.

The officers were unmoved.

“Don’t you all have mothers?” Hermilda asked.

When word was passed up the ranks that Pablo Escobar’s mother and sister had come, they were allowed to pass. With an escort they moved through the flanks of parked cars to where the lights of the ambulances and police vehicles flashed. Television cameras caught them as they approached, and a murmur went through the crowd.

Hermilda crossed the street to a small plot of grass where the body of a young man was sprawled. The man had a hole in the center of his forehead, and his eyes, grown dull and milky, stared blankly at the sky.

“You fools!” Hermilda shouted, and she began to laugh loudly at the police. “You fools! This is not my son! This is not Pablo Escobar! You have killed the wrong man!”

But the soldiers directed the two women to stand aside, and from the roof over the garage they lowered a body strapped to a stretcher, a fat man in bare feet with blue jeans rolled up at the cuff and a blue pullover shirt, whose round, bearded face was swollen and bloody. He had a full black beard and a bizarre square little mustache with the ends shaved off, like Hitler’s.

It was hard to tell at first that it was him. Hermilda gasped and stood over the body silently. Mixed with the pain and anger she felt a sense of relief, and also of dread. She felt relief because now at least the nightmare was over for her son. Dread because she believed his death would unleash still more violence. She wished nothing more now than for it to be finished, especially for her family. Let all the pain and bloodshed die with Pablo.

As she left the place, she pulled her mouth tight to betray no emotion and stopped only long enough to tell a reporter with a microphone, “At least now he is at rest.”

THE RISE OF EL DOCTOR

1948–1989

1

There was no more exciting place in South America to be in April 1948 than Bogotá, Colombia. Change was in the air, a static charge awaiting direction. No one knew exactly what it would be, only that it was at hand. It was a moment in the life of a nation, perhaps even a continent, when all of history seemed a prelude.

Bogotá was then a city of more than a million that spilled down the side of green mountains into a wide savanna. It was bordered by steep peaks to the north and east, and opened up flat and empty to the south and west. Arriving by air, one would see nothing below for hours but mountains, row upon row of emerald peaks, the highest of them capped white. Light hit the flanks of the undulating ranges at different angles, creating shifting shades of chartreuse, sage, and ivy, all of them cut with red-brown tributaries that gradually merged and widened as they coursed downhill to river valleys so deep in shadow they were almost blue. Then abruptly from these virgin ranges emerged a fully modern metropolis, a great blight of concrete covering most of a wide plain. Most of Bogotá was just two or three stories high, with a preponderance of red brick. From the center north, it had wide landscaped avenues, with museums, classic cathedrals, and graceful old mansions to rival the most elegant urban neighborhoods in the world, but to the south and west were the beginnings of shantytowns where refugees from the ongoing violence in the jungles and mountains sought refuge, employment, and hope and instead found only deadening poverty.

In the north part of the city, far from this squalor, a great meeting was about to convene, the Ninth Inter-American Conference. Foreign ministers from all countries of the hemisphere were there to sign the charter for the Organization of American States, a new coalition sponsored by the United States that was designed to give more voice and prominence to the nations of Central and South America. The city had been spruced up for the event, with street cleanings and trash removal, fresh coats of paint on public buildings, new signage on roadways, and, along the avenues, colorful flags and plantings. Even the shoe-shine men on the street corners wore new uniforms. The officials who attended meetings and parties in this surprisingly urbane capital hoped that the new organization would bring order and respectability to the struggling republics of the region. But the event had also attracted critics, leftist agitators, among them a young Cuban student leader named Fidel Castro. To them the fledgling OAS was a sop, a sellout, an alliance with the gringo imperialists of the north. To idealists who had gathered from all over the region, the postwar world was still up for grabs, a contest between capitalism and communism, or at least socialism, and young rebels like the twenty-one-year-old Castro anticipated a decade of revolution. They would topple the region’s calcified fuedal aristocracies and establish peace, social justice, and an authentic Pan-American political bloc. They were hip, angry, and smart, and they believed with the certainty of youth that they owned the future. They came to Bogotá to denounce the new organization and had planned a hemispheric conference of their own to coordinate citywide protests. They looked for guidance from one man in particular, an enormously popular forty-nine-year-old Colombian politician named Jorge Eliécer Gaitán.

“I am not a man, I am a people!” was Gaitán’s slogan, which he would pronounce dramatically at the end of speeches to bring his ecstatic admirers to their feet. He was of mixed blood, a man with the education and manner of the country’s white elite but the squat frame, dark skin, broad face, and coarse black hair of Colombia’s lower Indian castes. Gaitán’s appearance marked him as an outsider, a man of the masses. He could never fully belong to the small, select group of the wealthy and fair-skinned who owned most of the nation’s land and natural resources, and who for generations had dominated its government. These families ran the mines, owned the oil, and grew the fruits, coffee, and vegetables that made up the bulk of Colombia’s export economy. With the help of technology and capital offered by powerful U.S. corporate investors, they had grown rich selling the nation’s great natural bounty to America and Europe, and they had used those riches to import to Bogotá a sophistication that rivaled the great capitals of the world. Gaitán’s skin color marked him as apart from them just as it connected him with the excluded, the others, the masses of Colombian people who were considered inferior, who were locked out of the riches of this export economy and its privileged islands of urban prosperity. But that connection had given Gaitán power. No matter how educated and powerful he became, he was irrevocably tied to those others, whose only option was work in the mines or the fields at subsistence wages, who had no chance for education and opportunity for a better life. They constituted a vast electoral majority.

Times were bad. In the cities it meant inflation and high unemployment, while in the mountain and jungle villages that made up most of Colombia it meant no work, hunger, and starvation. Protests by angry campesinos, encouraged and led by Marxist agitators, had grown increasingly violent. The country’s Conservative Party leadership and its sponsors, wealthy landowners and miners, had responded with draconian methods. There were massacres and summary executions. Many foresaw this cycle of protest and repression leading to another bloody civil war—the Marxists saw it as the inevitable revolt. But most Colombians were neither Marxists nor oligarchs; they just wanted peace. They wanted change, not war. To them, this was Gaitán’s promise. It had made him wildly popular.

In a speech two months earlier before a crowd of one hundred thousand at the Plaza de Bolívar in Bogotá, Gaitán had pleaded with the government to restore order, and had urged the great crowd before him to express their outrage and self-control by responding to his oration not with cheers and applause but with silence. He had addressed his remarks directly to President Mariano Ospina.

“We ask that the persecution by the authorities stop,” he’d said. “Thus asks this immense multitude. We ask a small but great thing: that our political struggles be governed by the constitution. . . . Señor President, stop the violence. We want human life to be defended, that is the least a people can ask. . . . Our flag is in mourning, this silent multitude, this mute cry from our hearts, asks only that you treat us . . . as you would have us treat you.”

Against a backdrop of such explosive forces, the silence of this throng had echoed much more loudly than cheers. Many in the crowd had simply waved white handkerchiefs. At great rallies like these, Gaitán seemed poised to lead Colombia to a lawful, just, peaceful future. He tapped the deepest yearnings of his countrymen.

A skillful lawyer and a socialist, he was, in the words of a CIA report prepared years later, “a staunch antagonist of oligarchical rule and a spellbinding orator.” He was also a shrewd politician who had turned his populist appeal into real political power. When the OAS conference convened in Bogotá in 1948, Gaitán was not only the people’s favorite, he was the head of the Liberal Party, one of the country’s two major political organizations. His election as president in 1950 was regarded as a virtual certainty. Yet the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Author biography

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Killing Pablo by Mark Bowden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.