![]()

1

Introduction

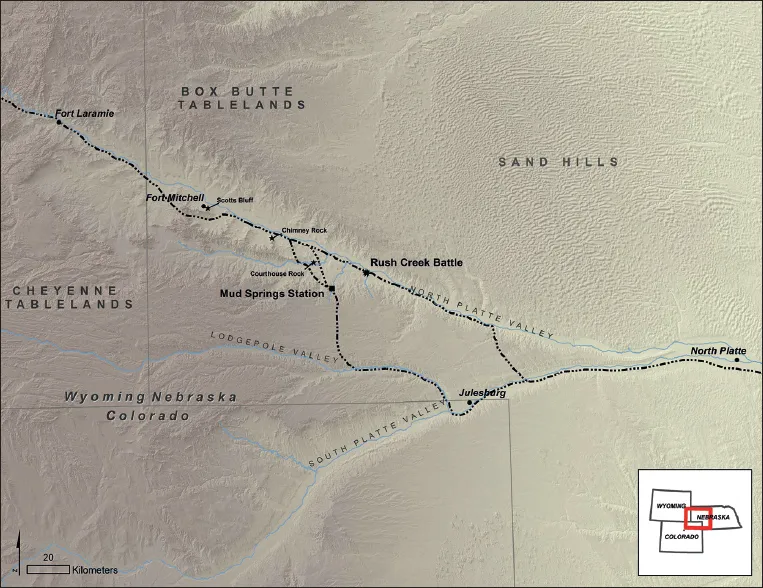

For a period of about week in early 1865, the Civil War swept across western Nebraska, focused on the valley of the North Platte River (see Fig. 2.1). The fighting that marked this event barely compares to the massive campaigns and terrible carnage that marked the conflict that was taking place in the eastern states. It did not even compare with the fighting that involved Confederate and Federal forces in the American southwest and other portions of the war in the Trans Mississippi West. Indeed the conflict in Nebraska saw essentially no Confederate involvement. The adversaries were disaffected Native fighters and U.S. Volunteer cavalrymen who had been sent to the frontier. Interestingly, the perspectives of the Cheyenne fighters was also recorded.

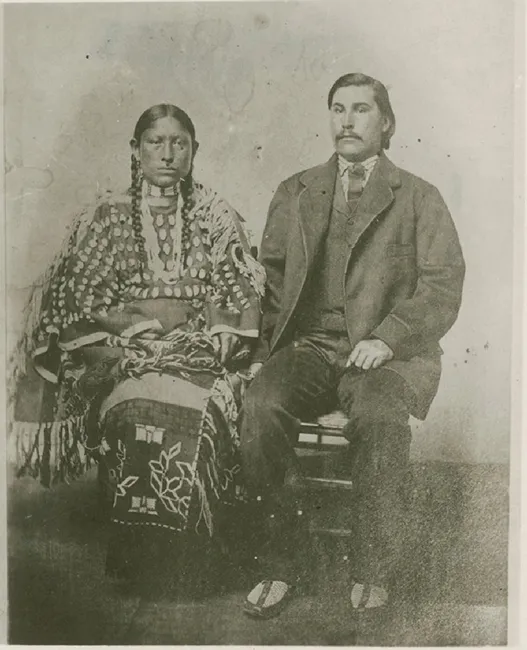

George Bent, son of frontier trader William Bent, who had taken a Cheyenne wife, Magpie, rode with his Cheyenne kinsmen and friends during this fighting (Fig. 1.1). Years later he wrote down his recollections and shared them in widely distributed sources. The fighting contributed little if anything to resolution of the Nation’s Civil War although it helped to set the tone and course of the Indian War that developed thereafter. The Volunteers remembered this fighting as “their War” and some young men on both sides were killed in these events. The story of this fighting is worth relating and that is one of the aims of this book. More than merely describing the evidence of the 1865 North Platte Campaign, this volume has another general aim. The North Platte Campaign offers a worthy illustration of the approach and analytical power of modern landscape-based conflict archaeology. We respect the effort and actions of the parties who fought on the North Platte, but our primary goal is to use the material reflections of their actions as means of understanding what they did and refining how archaeology can study the life and death human behavior that is combat.

Like many of the conflicts of interest to modern researchers, the North Platte skirmishes were between culturally different opponents. In later pages we will review the details of the campaign, but in simple summary, the fighting began on 4 February 1865 and lasted until shortly after the 10th. There were two fairly serious engagements, the first at a small waterhole called Mud Springs and the second in a field near the mouth of small stream that no-one any longer calls Rush Creek. There were probably far fewer than 1000 fighters involved in those skirmishes, but before, after, and between them, they involved several large movements of people and equipment. The equipment the conflicting sides used at these fights is essentially identical to the arms and gear that was in service to other Civil War era combatants. They also seem to have used approaches that were typical of America’s western warfare.

George Bent

George Bent, the son of frontier trader William Bent and the Cheyenne Owl Woman was born in 1843 at his father’s trading post, Bent’s Fort (now Bent’s Old Fort National Historic Site, Colorado). He was raised in two cultural worlds, the Cheyenne and Euro-American. He was educated in Kansas City and at Webster College near St Louis. When the Civil War broke out George joined the Missouri State Guard, a southern leaning military commanded by former Missouri Governor Sterling Price. Bent fought in the 1861 battles of Wilson’s Creek and Lexington. He was with Landis’s Artillery Battery at the March 1862 Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas. After Pea Ridge his unit was converted to an artillery unit of Missouri Confederate units. Bent was present at the Battle of Cornith. Shortly after Bent either deserted the Confederacy or was captured by Union troops. He was returned to St Louis and spent a brief time in Gratiot Street Prison but, due to the prominence of his family in the western trade, he was released and allowed to sign an oath of allegiance. He then returned to his southeast Colorado home. He joined his mother’s band of Cheyenne, preferring their ways to that of a fur trader.

Bent was present in Black Kettle’s village when it was attacked by John Chivington’s Colorado Volunteers in 1864 and was so effected by that event he joined the Dog Soldier Society and fought with them through 1867. He is believed to have been present, or actively participated, in 27 Cheyenne war parties or fights, including Mud Springs, Rush Creek and the 1866 Fetterman Fight near Fort Phil Kearney, Wyoming.

In 1867 Bent became an interpreter for the Cheyenne and U.S. Government. He maintained that role for many years. He married Magpie, Black Kettle’s daughter, who died in 1886. Afterward he married two other Cheyenne women. He had a total of six children.

In 1901 Bent met and began a collaboration with anthropologist George Bird Grinnell and shortly thereafter with George Hyde (1983). Although not realized in his lifetime Grinnell’s and Hyde’s books on the Cheyenne are largely the result of Bent’s knowledge of the tribe and the many Cheyenne Bent knew and who he encouraged to communicate with both Grinnell and Hyde. George Bent succumbed to the flu pandemic in 1918 at Washita, Oklahoma. For further biographical details of Geroge Bent see Hyde (1983) and Halaas and Masich (2004).

Fig. 1.1 George Bent and Magpie (courtesy University of Colorado Library Archives, Bent-Hyde Collection)

When this fighting was over and the sides had parted, the combat moved away. War between the U.S. Army and Native Communities was hardly ended, but it was over in this portion of the North Platte valley.

Conflict archaeology and the North Platte Campaign

Conflict archaeology has emerged as a modern discipline with a strong conceptual and popular base. Investigation of battlefields exposes events and places that evoke curiosity and deep cultural meaning. Archaeological study of combat also addresses momentous human behaviors. Among other approaches, microhistory has encouraged archaeologists to recognize the closely rooted connections that link very specific activities and broad trends of human development. Battlefield research developed out of anthropological and historical archaeology, but as it has been pursued around the world, it has embraced a range of theories, methods and a distinctive suite of techniques. Finding the debris of conflict and assessing it in behavioral terms have exposed the history of weapon technologies and political evolution (Keeley 1996). Archaeological investigation has exposed unrecognized conflicts of the past and clarified historic events that were either unclearly recalled or differently interpreted. Archaeological research has also supported memorialization, celebration, and preservation of sites and conflicted landscapes that have been deemed worthy of recognition. Archaeological investigation of battlefields has led to conceptual and technical growth in the discipline. Identifying the artifacts of war has presented conflict researchers with a welter of technical challenges, but interpreting and understanding battle debris in behavioral terms is an even greater challenge.

By their nature, military activities have to take place in regional space. Before serious combat can take place, arms and other resources have to be assembled. Skills have to be developed; Forces arranged; operations organized; and adversaries have to be met. All of those activities are impacted by cultural and natural environments and that means that conflict archaeology is well suited to the approaches of landscape archaeology. Finally, addition to its internal conceptual growth, battlefield archaeology has also found interpretive structures that speak directly to the combat. Military theoreticians have developed conceptual tools to plan and conduct military activities. This body of vocabulary and concepts describes military activities and deals directly with the tools and actions of combat. For those reasons they fit well with the interpretive challenges of battlefield archaeology. Like any ethnographic information, these sources must be used appropriately, but they offer specific insights that can speak directly to the relationship between conflict debris and the behavior that created it.

The North Platte Campaign offers a good basis for the application of landscape approaches to conflict archaeology because of its scale. This fighting is both easily approached and encompassed. The brevity of the conflict and the fact that the North Platte region has been developed into stable agricultural terrain means that archaeological evidence of the Campaign has survived with good integrity. Once rediscovered, these battlefields are much as they were when they were created. The landscapes around them are still open and not massively rearranged. As the research reported here was underway, highly detailed Light Ranging and Detection (LiDAR) imagery acquired as part of a surveying network of Nebraska’s water resources spread up the North Platte and made assessment of the battlefields and their contexts excitingly accessible.

The chapters that follow present what is historically known of the Campaign – the importance of the area as a focus for traffic along major trail routes; the military background to the brief but intense conflict; the protagonists; the location of the various skirmishes; and the course of those engagements as described in historical sources and eye-witness accounts. The concept of ‘battlespace’ and a ‘Levels of War’ model, recently adapted from modern military tactical operations to the analysis of past conflicts and archaeological data, are introduced along with other recently developed methods of and approaches to the analysis of battlefield archaeology. The field evidence for the identification of the actual sites of the two most important battles at Mud Springs and Rush Creek is presented. The distribution of relatively scant and scattered archaeological remains on a battlefield site can tell only a very partial story and so we combine the physical and historical evidence with topographical analysis and a consideration of the likely tactics and strategies employed by the adversaries in order to develop a more holistic understanding of the battlespaces of the North Platte Campaign.

![]()

2

Landscapes and dynamics of the Platte valley in 1864 and 1865

Forms and features of the Platte valley landscape

Modern Midwesterners do not like to hear their area called “flyover country” because it seems to suggest that crowded areas to the east or west are more interesting, attractive and important. Even in 1864 and 1865, however, most Americans could reasonably view western Nebraska as a “pass through” zone. It was a region travelers crossed on their way to somewhere else. The Platte valley offered travelers going west or east a nearly straight route across the central Plains. For most of them, the valley’s relatively flat expanse might seem to blend well with the broad lands that surround it. In terms of topography and landscape, however, the Platte valley is a rather complex corner of the Central Plains and its complexities influenced the military undertakings that occurred there.

The Platte River is formed by the confluence of two major water courses, the South Platte and North Platte Rivers and flows along a broadly looping course east to debouch into the Missouri River which forms the state boundary between Nebraska and Iowa. Between them these three watercourses effectively bisect the entire State of Nebraska. Viewed from the west this confluence is a “meeting” that points rather directly toward the east. From the east, however, it is a separation that divides a clearly defined swathe across the Plains into northern and southern routes (Fig. 2.1). The confluence takes place gradually over a section of braided and parallel courses in Keith and Lincoln counties. It is rather arbitrarily marked today by the modern city of North Platte. Historically it was associated with Cottonwood Springs Station (1862), later renamed Fort Cottonwood and then Fort McPherson (now the site of a National Cemetery). The reality is that travelers along the Platte valley would have seen little variation over the 150 miles (240 km) or so between Fort Kearney and the location of modern Ogallala. West of that point the North and South Platte Rivers begin to point in their separate directions and take on very different characters.

Fig. 2.1 Map of North Platte Campaign region of Nebraska showing the overland trails and military posts along the trail in 1865 (map by the authors)

The South Platte rises as a series of mountain streams in central Colorado and enters Nebraska from the southwest. Once out of the mountains, the river crosses flat-lying plains. Its valley is not markedly separated from the lands that surround it. It is quite flat and in the past may have supported small stands of trees. It is rightly thought of a Plains river.

The North Platte River presents a more complex landscape. It flows in a great sweep across southeastern Wyoming and the Nebraska panhandle. Fed by mountain runoff, the North Platte maintains a rather steady flow, but with an annual precipitation of 14–18 in (c. 36–47 cm), the region it crosses can only be described as semi-arid. Away from the river, the valley is generally dry.

To reach the confluence with the South Platte, the North Platte cuts through a series of geological deposits that define and isolate its valley. Exposed bedrock forming the north and south sides of the valley is assigned to the White River and Arikaree groups. It is composed mainly of soft, mostly light colored sedimentary rocks. In many areas the stone layers form steep, even rugged bluffs, but in others the strata are interspersed with wind and water deposited sand, silts and loess (Swinehart et al. 1985; Swinehart and Diffendal 1995). With its distinctive set of environment characteristics, the North Platte valley is composed of four separate regions (Diffendal 1993).

The River course

The central core of the both the South Platte and North Platte valleys are the rivers themselves. The size and character of the North Platte River has changed in recent years, but even with the reduced flows that have resulted from intensive irrigation, the river flows across a broad swath of flat-lying land (Fig. 2.2). Whatever its state, the river course is easily approached since it does not lie in a deeply incised channel, in fact, this stretch of the river is the most easily traversable part of the valleys. Crossing the river without a bridge would, however, be a challenge in any season. At times of low water much of the river course is a swathe of loose fine sand. At times of high water the same area is characterised by a swift current that might be several feet deep. In winter, the river course may be covered by a broad sheet of ice. Gallery forests and thickets that grow along the modern river appear not to have been present in pre-modern times. The lack of vegetation may have helped make travel along the river course easy, but it also meant that travelers had few sources of fuel in this part of the valley.

North Platte valley-side slopes

The floor of the North Platte valley is formed by moderately sloping land that reaches from the edge of the river to the base of the bedrock escarpments that define the valley (Fig. 2.2). As noted, land adjacent to the river is quite flat. Most of the streams that cross the valley sides enter the river as shallow meanders that can be easily crossed. The flat regularity of lower portions of the valley sides made it attractive to early travelers. The Mormon and California and Oregon Trails, which together form the major overland trail, ran along the south side of the river very near the edge of the water. This flat, open space also afforded travelers a broad view blocked by neither terrain nor vegetation. Even travelers beyond eyeshot could often be seen by the dust they raised. This is because fine sands and silt in this part of the valley are easily disturbed when the light grass cover is interrupted. In technical terms, the valley-side soils are assigned as Valent soil. They are composed of eolian sand and loam weathered, washed and blown off limestone outcrops on the valley margins. These soils do not hold water well, thus they are dry and susceptible to wind and water erosion. They are also soft and easily dug (1985 Soil Survey of Morrill County, Nebraska, Natural Resources Conservation Service, US Department of Agriculture).

Fig. 2.2 The broad sweep of the North Platte Valley is seen here. Land adjacent to the river is relatively flat. Lands to the south rise slightly in a series of ancient terraces, while the land on the north side of the river is the base of bedrock escarpments that help define the valley (photo by Peter Bleed)

Away from the river, the valley-side slopes rise...