![]()

CHAPTER ONE

The Most Hated Tree?

Sitka spruce is now the most important commercial forest tree species in Ireland.

Padraig Joyce and Niall OCarroll 2002

And yet, it is popularly denigrated, even vilified, and the undiscerning public is blind to its virtues, and is encouraged to be so by legions of misguided conservationist ‘green’, ‘natives only’ and anti-forestry bodies.

Alan Mitchell 1996

An astonishingly lush, tall, damp and dank, dense and dark, group of forest ecosystems clothe the Pacific Ocean coast of Canada and the United States of America. Towering trees grow right down to the sea shore, along the banks of inlets and estuaries and on steep, coastal mountainsides typically to about 500 m (1640 ft), but occasionally up to 2700 m (8858 ft) altitude.

These unusual ‘temperate rainforest’ ecosystems have developed and colonised a narrow coastal belt from northern California to Alaska, a distance of 3600 km (2237 miles). Although it is usually no more than 80 km (50 miles) wide from the ocean to its inland purlieu, it develops further inland along river flood-plains and fjords. In a ribbon of mild, misty, high rainfall, maritime climate, these complex and biologically-productive forests are dominated by a few groups of plants: conifers, lichens and bryophytes (mosses and liverworts).

Conifers are woody shrubs or trees with an ancient geological lineage, appearing in the geological record during the Carboniferous period about 300 million years ago (mya). Their foliage is usually evergreen, of green scales or needle leaves. The branches are arranged in whorls round the trunk becoming gradually smaller up the tree. This gives most conifers a single trunk and regular tree-shape, often pyramidal or conical. Their shape is one reason UK silviculturalists (people who grow and manage woodlands) today prefer growing conifers to broadleaved trees like oak or ash which have irregular branches. Conifers are easily grown, with straight trunks, while their whorls of branches are easily removed, giving a clean ‘bole’, suitable for cutting into shorter lengths by machinery. Millions of pit-props to support the tunnels of deep coal mines were produced like this from conifers during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in Europe. Modern timber, too, has to be long and straight for today’s construction spars, planks and paper-making machinery.

In contrast, the asymmetrical, irregular growth pattern of broadleaved trees with their ‘kneed’ and angled branches was exploited in past centuries and millennia. Their trunks were important for constructing boats, for structural components of medieval buildings like crucks (curved timbers to support a roof) and harbours; their irregular branches were suitable for wooden wheels, implements, tools, clogs and charcoal.

We now rarely travel in wooden boats, or walk in clogs, so modern sawmills and pulp mills buy mainly conifer timber, to manufacture the different products needed by modern society: us.

Commercial timber in North America comes from many types of deliberatelyplanted conifer and broadleaved forests and from indigenous forest ecosystems. Forests are regenerated by deliberate planting of little trees from nurseries, or naturally from seeds produced by the tree canopy which drop or blow onto the ground, germinate and grow. In well-forested parts of Europe, the same methods are used. But in Britain and Ireland, forest cover was reduced time after time during prehistory and history, so that by 1900 AD less than 5% of their land area was woodland. So there is little, if any, indigenous forest extant in these countries. Most commercial timber is produced from tree seedlings germinated and grown in nurseries, then planted out as forests. Sitka spruce is one of the most common conifers in modern British and Irish forests.

The Sitka spruce (Picea sitchensis), with its prickly, blue-green needle-leaves and orange-brown cones, is one of the most abundant, tall and large-girthed conifers in the temperate rainforests of western North America. In some localities it is the dominant or only tree species. However, since Sitka spruce is naturally confined to temperate rainforests, which are restricted geographically, it is also rare. It is highly valued in modern North America as an economic tree for its good quality construction timber and paper pulp. (Chapters Two and Three explain the origin and features of spruce trees).

Other conifers contributing to the North American temperate rainforests are Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), Western red cedar (Thuja plicata), Western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), Mountain hemlock (T. mertensia) Pacific silver fir (Abies amabilis), Grand fir (A. grandis) and Yellow cedar (Chamaecyparis nootkatensis). These are important conifers commercially as well as ecologically. A variety of broadleaved trees also contribute to the temperate rainforest, including Bigleaf maple (Acer macrophyllum), Red alder (Alnus rubra) and Black cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa).

There are said to be more Sitka spruce trees in Britain and Ireland than in North America today. It was first introduced into Europe during the early nineteenth century, when exploring was arduous and dangerous. Plant hunters sent seeds of many trees, including Sitka spruce, home to Europe from North America. British scientific and horticultural societies were looking for trees which would grow on the poor soils and thrive in the wet, windy climate of the uplands, as well as for attractive plants to enhance parks and gardens of country mansions. Many other seeds and plants – hundreds of species – arrived in Europe from North America. Other continents were also searched for potentially valuable and beautiful trees and herbaceous plants.

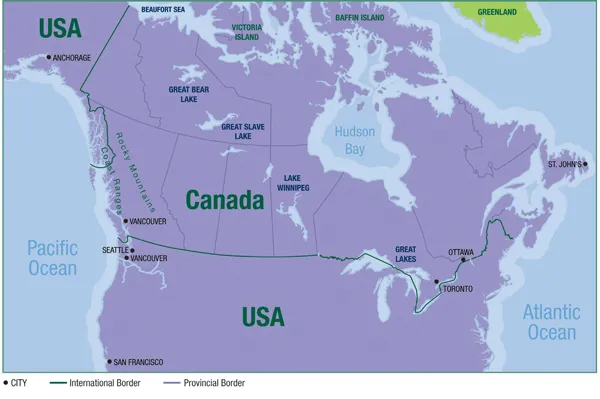

Maps 1 and 2, of the UK and Republic of Ireland and North America respectively, show their geographical features relevant to this book.

The potential of Sitka spruce for Scotland’s landscapes was recognised by the first explorer to send seeds back and later by landowners themselves. It grew well and looked beautiful in their gardens and arboreta. During the later nineteenth and twentieth centuries, landowners and foresters in many parts of Britain and Ireland tested its growth in plantation conditions. They discovered that it would establish and grow fast in some of the exposed, wet conditions and difficult soils of the north and west. This ability, as well as its products, endeared it to professional foresters, private landowners and timber merchants.

But for today’s public, Sitka spruce is the tree species in their countryside, which is probably the most loathed … even though the public usually loves trees.

For instance, the two common oaks, Pedunculate (Quercus robur) and Sessile (Q. petraea), represent historic, cultural, aesthetic and user appeal (the Knightwood Oak, the Bloody Oak, King James Oak and Cefnmabli Oak). But the British public cannot find any similar empathy with the Sitka spruce, even though it is now the most common tree species in upland landscapes. People do not see in Sitka spruce the grandeur and rarity of the riparian Black poplar (Populus nigra subsp. betulifolia) or the religious and mythical appeal of the yew (Taxus baccata), nor can it be used to make the traditional longbows of prehistory and medieval times.

• Unlike the stately English elm (Ulmus minor var. vulgaris), Sitka spruce has not been a familiar hedgerow tree of lowland farms.

• Unlike the hazel (Corylus avellana) and limes (Tilia species) it does not form coppice woodlands with spectacular assemblages of spring flowers.

• Unlike the Field maple (Acer campestre) it does not metamorphose into orange autumn foliage, not does it rustle plaintively in the wind like the aspen (Populus tremula).

• Unlike the Wild cherry (Prunus avium), Crab apple (Malus sylvestris) and Rowan (Sorbus aucuparia) it offers neither floriferous spring canopies nor edible fruits.

• British and Irish people denigrate Sitka spruce with ‘introduced’ and ‘conifer’ when reflecting upon trees in the countryside.

Britain has merely three indigenous conifer species: yew, juniper and Scots pine. It has no native spruce species. Yew grows singly, or in groups, in churchyards, along important land boundaries and in other woodlands; there are a few pure yew woodlands in southern England and Ireland.

Juniper (Juniperus communis) has declined, grazed away by centuries of sheep and cattle ranching in the uplands. A few woodlands of tall juniper grow in Scotland, while patches of the prostrate sub-species scent the air of southern English chalk hills.

The Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) and hazel formed large forests in middle Britain during the warm, dry Boreal period from about 9000 to 7000 years before the present (bp). When the climate subsequently cooled and wetted, Scots pine retreated north. Today, native Scots pine woodlands grow only in some Scottish glens, along some loch shores and islands.

MAP 1. UK and Republic of Ireland, prepared by Susan Anderson of Eikon Design, Ayrshire, UK.

SOURCE: ATLASES.

MAP 2. North America, prepared by Susan Anderson.

SOURCE: ATLASES.

After the last Ice Age, broadleaved trees gradually colonised Britain and Ireland, clothing much of the landscape with deciduous forests from about 8000 BP. Without human interference, they might still form the dominant native vegetation. British and Irish people are used to broadleaved trees – not needled conifers – forming the hedges, woodlands, forests and coppices of their beloved countryside. However, not only are there only three indigenous conifer species, there are few broadleaved species either compared with continental Europe.

During the latest glacial episode of the Ice Ages (called the Devensian in Europe) 110,000 to 12,000 BP, what are now Britain and Ireland were part of the European continent. Most plants and animals became extinct in ice-covered northern Europe. But from recent genetic and distribution evidence, we know that some arctic-alpine plants and invertebrates survived in small numbers on ice-free peaks or ‘nunataks’ amongst the ice fields. And some trees somehow survived in Scandinavia: DNA evidence suggests that Scots pine and Norway spruce (Picea abies) lived on through the last glaciation on nunataks in Norway. Palaeolithic (Old Stone Age) people, however, had gone south to warmer places – as they do now!

After an exceptionally cold spell at about 18,000 BP, temperatures gradually increased, ice sheets and glaciers started to melt; flora, fauna and people began colonising the bare, wet, rocky landscape of northern Europe. Water from masses of melting ice flowed into the sea and the land lifted because the huge weight of ice dwindled. What are now Ireland and Britain were still joined by low-lying wetlands; Britain was joined to Germany and Denmark by a marshy plain recently christened Doggerland; southern England was separated from Belgium, the Netherlands and France only by the a river we call Fleuve Manche, flowing through a trench to the Atlantic Ocean.

Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age) hunter-gatherers initially migrated into Ireland, Britain and Scandinavia by land when the ice had completely retreated after about 12,000 BP. Those who lived in marshy, riparian and littoral areas led a good existence. There were abundant edible fish and shellfish in fresh, sea and brackish water; abundant large and edible wild animals such as Red deer, Wild boar and seals; abundant edible wildfowl from large cranes to tiny teal; and edible plants.

About 10,000 BP, the marshland link between Britain and Ireland was inundated by the rising sea. This new Irish Sea now separated the island of Ireland from the still-joined Britain and Europe.

During several centuries after 7800 BP, with further changes in relative sea and land levels, the low-lying marshes of Doggerland were gradually overwhelmed by sea-water. People’s environments were lost to encroaching seas and at least one tsunami. This catastrophe forced them to walk, swim or travel by home-made boat to drier land. The people who went west or north-west eventually became segregated from humans on the European mainland by the new North Sea.

By 7500 BP, sea levels had risen sufficiently that the Fleuve Manche was flooded by salt water: what we now call La Manche or the English Channel finally separated our fringing, north-west archipelagos from the main continent.

Only about 2000 years elapsed between the last of the ice and the formation of the new archipelago. Some wild plants and animals had migrated from their nunataks and ice-time asyla in south and south-eastern Europ...