![]()

PART I

The Roadmap

![]()

1

The Political Economy of Aid: Foreign Aid Effectiveness, Theories, Methods and the Challenges that Lie Ahead

MARCO ZUPI

I.The Ambiguous Nature of Foreign Aid

Seventy years ago, the US President Harry Truman’s inauguration speech on 20 January 1949 marked the beginning of a new ‘developmental’ era.1 The previous colonial period, characterised by the asymmetrical relations between the European mainland (the colonisers) and the colonised countries, was replaced by a new asymmetrical relationship between the rich OECD donors and the poor developing countries in the South of the world. The poor countries became the recipients of foreign aid, technically defined as Official Development Assistance (ODA) that consisted of grants, soft loans and technical assistance.2

The main objective of foreign aid was to assist poor nations in their development and fight against mass poverty, so as to approach the status of rich countries.

At the same time, foreign aid was part of a wider approach to foreign policy oriented to forge new alliances in the international chess match, based on the prevailing goal of national security in a period dominated by bi-polarism, through defence alliances such as NATO and the Warsaw Pact.

In practice, the world quickly discovered a gap between the rhetoric around the fight against poverty through foreign aid and the reality of the security priority during the Cold War. For the USA and the Western bloc, the war on poverty in developing countries had to be fought in order to limit the Soviet influence; the Eastern bloc tried to offer financial and military support to poor countries so that they would choose the Communist road to progress.

Thus, even though it is held that the term foreign aid is applicable if the capital transfer is for developmental and not military purposes, foreign aid has rarely been just based on disinterested motivations. Foreign aid has always been linked, to a considerable extent, to the national political interests of the donors: firstly security, peace and trade, including the goal to secure energy and resources supply.

II.The Proliferation of Goals

Even assuming that foreign aid was just driven by the altruistic ideals of solidarity to assist the poor and promote development, the conceptualisation of development after the Second World War paved the way for a patchwork of different aims, approaches and instruments rather than a coherent plan of financial and budgetary provisions for operational practice.

In practical terms, the juxtaposition of different priorities and financial instruments has caused the interaction of competing, confused and contradictory focuses and actions.

Sketchily summarising some of the main strands of development theory and aid policies that emerged in the past decades, the main rationale of foreign aid in the 1950s and 1960s was to provide the necessary capital resource transfer to allow poor countries to achieve a high enough savings rate to propel them into growth, with just an indirect attention to development issues (trickle-down).3 Thereafter, gradually a greater focus went to investing in human capital and raising the standard of living of the poor through increased employment opportunities. In the 1970s, a greater foreign aid focus on poverty meant more emphasis on direct interventions to benefit the poor – projects in agriculture, rural development and social services including housing, education and health – as instruments directly targeted to promote people’s development in general and in its multidimensional nature.4 In the late 1970s and early 1980s the situation changed dramatically and the global ascendancy of the ‘Washington Consensus’ dominated aid policy during the 1980s and the first half of the 1990s.5 The term denoted a neo-liberal macroeconomic manifesto, summed up by the three keywords of liberalisation, deregulation and privatisation and by the so-called market-friendly approach to development.6 In the context of the new pro-market and anti-state rhetoric, foreign aid went back to represent – as in the early 1950s and 1960s – a basic inflow to fill financial gaps (and allow poor countries to service their external debt), but also to support the implementation of structural transformation and adjustment of the economies through conditionalities, with an increased recourse to the private sector and NGOs in an effort to privatise aid.7

At the turn of the Millennium, the international political consensus on the development agenda led to the signature of the eight UN Millennium Development Goals (with 18 targets and 48 indicators that later became 60), strictly focused on social dimensions to address the dramatic situation of poverty.8

Subsequently, in 2015 a new consensus landed in a new pact, with a more complex and ambitious system of 17 goals, 169 targets and 232 indicators, the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) meant to address the three pillars of development (social, economic and environmental) and eradicate poverty.9

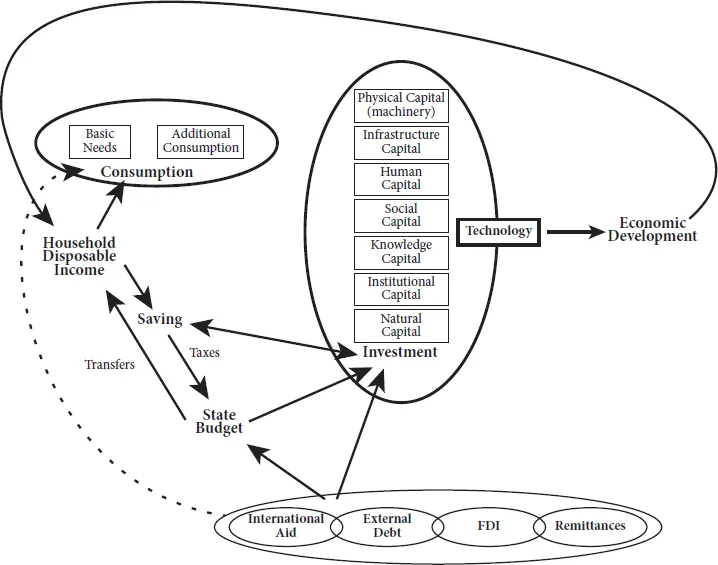

Thus, through the past decades the inspiring vision of economic development and capital accumulation has never changed, though only partial progress has been made with the global development agenda: poverty has not been eradicated and indeed, income inequality has increased between as well as within North and South, and environmental degradation and ecological imbalance has worsened. Above all, some additional and heterogeneous dimensions of capital have been included in the process of capital accumulation in order to better conceptualise the process of economic development. This vision has been used to prove the necessity of foreign aid for poor countries. Figure 1 provides a graphical representation of this vision. Capital accumulation has been considered the key to prosperity, and this comes about through industrialisation, based on a combination of increased savings (domestic and international savings, through foreign aid, external debt, foreign direct investment (FDI) and workers’ remittances) to be transformed into productive investment. Growth – conceived as the main development engine and based on a financial injection to support productive investments in physical and infrastructure capital10 – was additionally helped by investment (through financial support) in the following:

•Human capital (education, health, research and development as a way to increase skills, improve labour productivity and induce technological innovations).

•Social capital (institutions, social norms of trust and reciprocity among different actors, formal and informal relational goods, which can create a favourable environment to make investment more productive and efficient through direct support to the private sector and NGOs).

•Knowledge capital (in particular information and communication technology and the need to become – as mentioned in the EU Lisbon strategy adopted in 2000 by the European Council – a dynamic and competitive knowledge-based economy).11

•Institutional capital (taking for granted that institutions do matter a lot, the purpose is to promote the democratisation process, the rule of law, fight against corruption, decentralisation of political power and administration, high quality and managerial skills of organisations and public administration, capacity- and institution-building).

•Natural capital (assuming environment as a cross-cutting dimension or a mainstream in the development process, which can be adequately assessed only in the inter-generational perspective of the so-called sustainable development, as described in the UN Commission Report on sustainable development chaired by Gro Harlem Brundtland in 1987, during the Rio Summit in 1992 and the Rio+20 in 2012 and, finally, in the SDGs).

Figure 1 The Role of ODA in the Process of Capital Accumulation

III.The Process of Conditionality Accumulation

During the last 70 years, foreign aid has been funding infrastructure projects, social expenditures (particularly basic health and education), training activities (with technical assistance), private sector development, good governance and sustainable development projects. At the same time, there has been evolution for each of these components. In particular, increasing attention was paid to good governance so as to prevent an ineffective waste of money through aid and its negative impact on the local political context; however the elusive nature of this concept led to different interpretations amongst the actors involved in aid community. According to the UN discourse good governance means participation, ensuring the rule of law, democracy, transparency and capacity in public administration, by making governmental institutions, private sectors and civil society organisations accountable to the public and institutional stakeholders.12 According to a more restricted and technical view adopted by the World Bank, good governance is to be intended as the capacity of governments to formulate policies and have them effectively implemented and has to be translated into an effective public sector management of national resources. Since the 1980s, the World Bank has adopted a new framework to govern lending and debt relief programmes, by emphasising the need to make public sector management more effective in terms of budgeting, prioritisation, delivery, monitoring and strengthening of the civil service capacity. Translated into practical terms, good governance appeared just as a processing task, with public procurement policies, procedures and processes confined to the application of rules for government purchase of goods, services and works.13 This view was in conflict with the stated commitment to transparency and participation and induced a reconsideration of procurement as a critical management activity to support accountability and participation, with a more political relevance. In other terms, good governance is linked to the democratic process, and means the capacity of states to factor the common interest into ‘inclusive’ policies. Clearly, this approach based on multiple and evolving components has represented a flexible and indirect pro-poor strategy based on a trickle-down effect, rather than a policy directly focused on addressing just some specific needs identified by a narrow focus on poverty.

No specific instrument or purpose of foreign aid was completely substituted by new instruments and aims. Rather, a proliferation of objectives emerged as a structural characteristic of foreign aid together with a lot of different instruments and different approaches (sometimes representing different visions of development). Project aid and programme aid, commodity aid and balance of payments support, technical assistance, NGOs’ activities, sector programme and sector-wide approach, budget aid and decentralised co-operation coexist with difficulties and problems of coherence, because they can represent different visions and they are not simple instruments.

This cumulative approach to foreign aid as a sum of different, often rival but never contradictory dimensions of capital to be funded internationally in order to create a favourable context to address the needs of the poor, is confirmed by looking at the evolution of conditionality, a specific aid ‘instrument’ designed to improve the effectiveness and impact of aid.

Due to the fact that a grant given for one purpose can end up financing something else because, in the absence of foreign aid, the government itself financed the project (the so-called aid fungibility),14 donors – both governments and international financial institutions – have tried to induce recipient/partner countries to adopt some specific measures through the so-called conditionality.

As concerns this instrument there has been a cumulative approach as well.

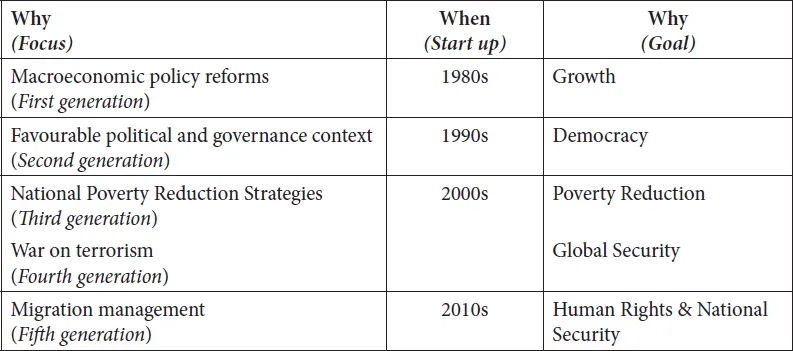

Table 1 Five Generations of Conditionalities

In the 1980s, after (and thanks to the opportunity offered by) the outbreak of the external debt crisis, the IMF and the World Bank, in accordance with the main Western donor countries, introduced the first generation of conditionality. These rules/guidelines urged the recipient governments to adopt market-friendly structural reforms and integration into the world economy as the best way to promote growth.

In the 1990s, after the collapse of the Soviet bloc, the community of international donors introduced a second generation of conditionality. The idea was that a favourable environment for making development effective is a mixture of sound macroeconomic policies and complementary political and institutional reforms in terms of good governance (in the more limited sense of better public sector management and accountability), rule of law, consolidation of democracy and respect for human rights. This occurred in the case of the EU during the renewal process of the Cotonou Agreement with the African, Caribbean and Pac...