![]()

Part I

National Euroscepticism and the EU Institutions

![]()

1

EU Policies in Times of Populist Radical Right Euroscepticism: Which Future?

GERDA FALKNER AND GEORG PLATTNER*

I.INTRODUCTION: THE EUROSCEPTIC CHALLENGE AND EU POLICIES

This book reaches beyond the usual top-down perspective of EU law, and it does so in many different ways. The following chapter adds to these multiple perspectives by turning the readers’ attention to populist radical right parties in the Member States and in the European Parliament (EP). What are their ideas for potentially reforming existing EU policies, such as the Economic and Monetary Union, EU environmental policy, and EU social policy? Where do these parties agree across countries and where not? Who disagrees with whom?

Given mounting right-wing electoral successes, we need in-depth knowledge about what these comparatively novel actors could bring about for policies that nowadays stretch far beyond the national level and, most importantly for our purposes, include the EU. One of the fundamental challenges these parties pose is their profound defiance of several policies developed over decades by the EU. This speaks to one of the major issues of our times: how will today’s major challengers to traditional democracy and of established European collaboration among states affect the EU?

The most likely scenario would involve the active reform of EU policies. Populist radical right parties (PRRPs) could form a bloc in day-to-day policy making (most importantly, in the EP, but also in all other institutions) to reform relevant EU policies according to one common template. If and where they are not strong enough in numbers, they may look out for additional ad hoc coalition partners from other parties. European governments are already led more often by representatives of the political right than left, and of the 11 populist parties in power in the EU, either alone or as coalition partners, seven could be described as PRRPs.

Table 1.1 Populist parties in government (EU28, by 8 November 2018)

Source: Own compilation.

Table 1.1 indicates that PRRPs are no longer fringe parties, which suggests that their impact on policies, including at the EU level, is likely to grow. However, the policy clout of the PRRPs would be expected to be larger if they were coherent in their objectives and motivations. By contrast, if PRRPs pull in opposite directions, their claims could more easily cancel each other out, so that their effect would be limited.1

So far, PRRPs have usually been considered as a bloc by political scientists because of their relative coherence on national policies and their general (but unspecific) Euroscepticism. Our study examines this assumption by comparing the parties’ programmes on specific EU policies. This chapter presents selected data from a wider research project and compares the programmatic claims of 16 national PRRPs with seats in the EP – according to the book’s ambition to study the intersection of national and EU levels. It seems to us that the combined challenge arising from many individual policy changes may, at least in the long run, challenge existing EU law, and attract as much attention as the – to date much more debated – issue of Brexit.

Our research question asks if the PRRPs’ programmatic documents expose a coherent vision regarding the reform of EU policies. It was necessary to build on established knowledge to determine the political parties to be included in our analysis. Thus, this project based itself on the rich political science literature analysing political parties. In other words, this study does not aim to establish which political party in the EU could or should be labelled ‘populist radical right’ or has elements of a RRRP, be it the ‘populist’, ‘radical’ or ‘right’. Instead, we use the political parties identified as ‘PRRPs’ by the literature. The seminal work by Cas Mudde from 2007 is used for the definition of key characteristics of the parties in question.2

The relevant literature specifies that ‘populist radical right’ parties are ‘populist’ in that they present themselves as the sole legitimate representatives of ‘the pure people’ whilst the other parties are regarded as part of ‘the corrupt elite’;3 are ‘radical’ in their ‘opposition to some key features of liberal democracy, most notably pluralism and the constitutional protection of minorities’;4 and are ‘right’ in that they believe ‘the main inequalities between people to be natural and outside the purview of the state’.5

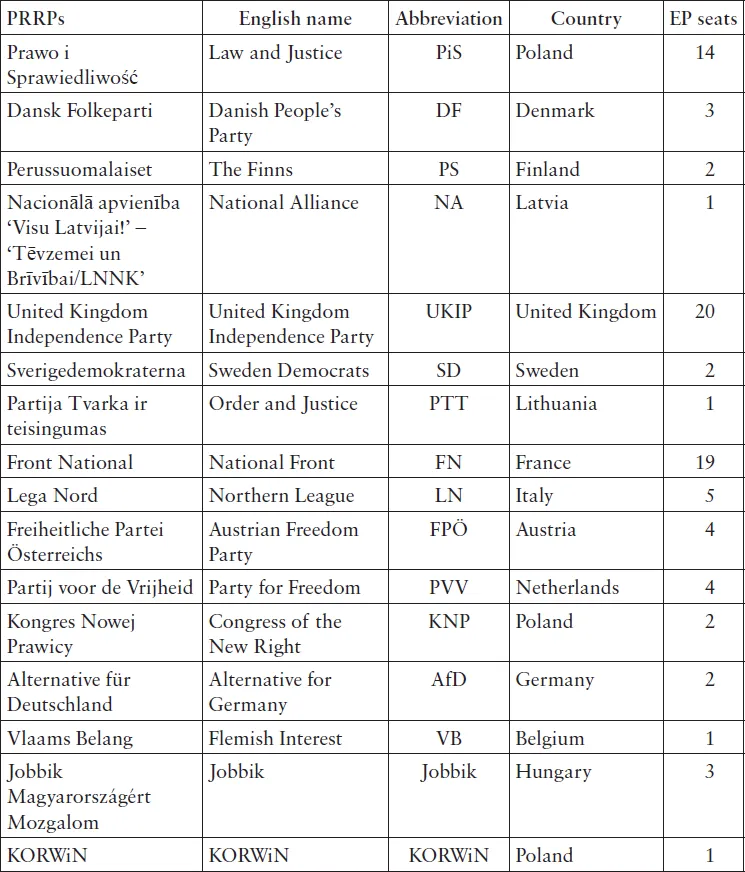

Following the mainstream consensus regarding a cluster of parties that are labelled PRRPs,6 we identify 16 national parties that are represented in the 8th European Parliament (2014–2019) as the objects of our study. Laid down in Table 1.2, this study covers 16 PRRPs: to the six parties identified in 2007 by Mudde, the Austrian FPÖ, the Belgian VB, the Danish DF, the Italian LN, the Swedish SD and the French FN;7 this chapter adds the Hungarian Jobbik, the German AfD, and the Dutch PVV, discussed by Mudde in later research;8 the Latvian NA;9 the Polish PiS, which significantly changed after 2007;10 the Finnish PS;11 the British UKIP after its recent transformation;12 and finally, the Lithuanian PTT.13

Table 1.2 Populist radical right Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) (overall: 172 of 751 MEPs, or 22.9 per cent) included in our study14

Source: Adapted from European Parliament (2018).15

II.METHODOLOGY

Our study covers all available programmatic documents of these parties in their most recent versions (i.e. 31 individual documents).16 This includes all 16 PRRPs’ election manifestos for the EP election of 2014; the official party programmes of all relevant national parties by the end of 2016 or, in the absence of such a document, the latest election programmes for pre-2016 national elections; and a few relevant policy documents that present the specific claims of any such party with regard to a specific EU policy.17 Election manifestos in particular, but also party programmes, are an outstanding source for extracting a party’s policy position because they embody a common denominator, regardless of the party’s internal structure. Our study closes a prominent gap in research since existing studies have looked at other, more indirect, sources for the assessment of policy positions. This includes votes on specific issues in the EP, but these votes are much more eclectic and not representative of a party’s own priorities regarding a specific EU policy.18 Furthermore, expert interviews and surveys, the second source for policy positions that is often relied on, offer valuable, but secondary assessments.19 Campaign statements as reported in the media may include more recent policy demands but are often ad hoc.20 By contrast, the party documents can be expected to be more impartial and as close as we can get to these parties’ common guidelines of will and intent.21

We use the method of qualitative content analysis to establish how coherent or incoherent the PRRPs’ policy ideas are.22 Our coding units are all specific statements, over 450 claims, pertaining to any EU policy or any item falling within a specific EU policy.23 The statements are then compared to the EU’s policy goals and instruments, as extracted from the EU’s primary law (Treaty on European Union/TEU, Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union/TFEU, Charter of Fundamental Rights, etc.), as well as the relevant secondary law documents (Directives, Regulations, etc.). Each specific goal, instrument or setting of a relevant policy is one specific code. ‘Double claims’ are not counted where they are coherent with each other but are covered individually where they are contradictory. Our findings are aggregated on the level of policy items and later of entire EU policies.

Our coding includes both the direction and the depth of any specific policy claim contained in the PRRPs’ documents studied. Regarding direction, we follow Bauer and Knill’s quest for increased or decreased governmental commitment in specific sectors.24 ‘Policy dismantling’ (Bauer and Knill’s primary research interest) occurs when the number of policy instruments or the intensity of their settings are lowered; the status quo scenario results in no change; or a number of changes lead to the same status if balanced out. Policy expansion is an increase in the number of policy instruments or the intensity of their settings. Regarding the intensity of suggested policy change, we follow Hall’s concept: first order change refers to new settings of existing instruments; second order change to new instruments or fewer instruments than before; and third order change to new (ordering of) goals of the policy or cancellation of previous goals.25

As to the policy change’s coherence, we distinguish between ‘absolute coherence’ and ‘goal coherence’. ‘Absolute coherence’ is achieved if there are no inconsistencies on any level of claimed policy change.26 ‘Goal coherence’ means coherence regarding the proposed change on the level of goals.27

On the level of EU policies, we distinguish three clusters that are concerned with different overarching policy topics: core state powers (section III); a new politics cluster (section IV); and a socio-economic cluster (section V).28 This chapter only discusses policy areas that received more than ten statements from parties and, hence, excludes areas that are of interest to only a few of the relevant parties.

III.(IN-)COHERENCE IN CLUSTER 1: CORE STATE POWERS

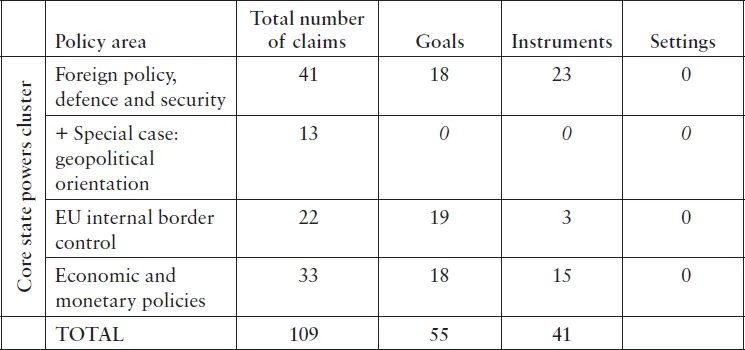

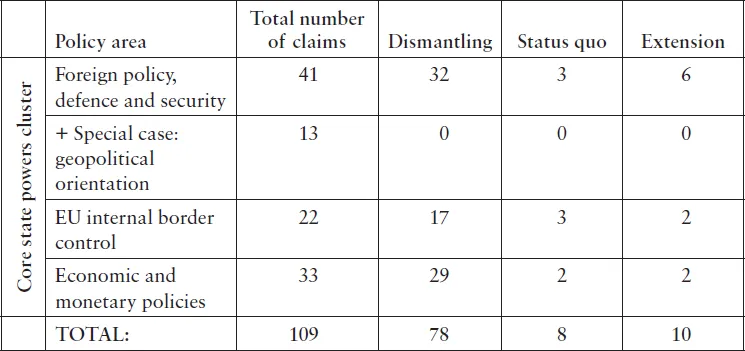

The first cluster deals with policies that are concerned with core state powers. Core state powers are the powers of a state that ensure its monopoly of legitimate coercion and its monetary autonomy.29 The cluster in our study comprises three different policy areas, set out in Table 1.3: the EU’s Foreign Policy, Defence and Security, intra-EU border control, and the EU’s economic and monetary policies. Table 1.4 represents the policy claims in this cluster.

Table 1.3 National PRRPs’ policy claims in EU policy areas: depth of change for core state powers

Source: Own compilation.

Table 1.4 PRRPs’ policy claims in EU policy areas: direction of change for core state powers

Source: Own compilation.

A.Common Foreign, Defence and Security Policies

Let us first focus on the EU’s common foreign, defence and security policies, which have by far the most statements of all policy areas in the cluster. At first glance, the parties do indeed oppose attempts to integrate this policy area at the EU level: when it comes to the RRPs’ predominant direction of change, dismantling is much more prominent (78 per cent) than extending the policy.

On a closer look, however, the picture becomes more nuanced. On the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), there would be absolute coherence towards dismantling goals and instruments if the Lithuanian PTT did not support the CFSP as a policy goal in rather general terms and if the Latvian NA did not support one of the CFSP’s instruments, the Eastern Partnership. Dismantling is claimed seven times regarding the goal of developing a common foreign policy (German AfD, French FN, Polish KNP, Italian LN, Dutch PVV, Polish PiS, Latvian NA) and four times regarding instruments (‘EEAS’: German AfD, Italian LN, Belgian VB; ‘Embassies’: Dutch PVV).

Another topic, usually connected to the foreign and security policy realm, deserves our attention. ‘Geopolitical orientation’ is neither a goal nor an instrument and cannot, hence, be coded like the claims discussed above. Nevertheless, geopolitical orientation is a crucial factor to understand the general directions of a state’s external policies. It seems that, considering the global constellation of alliances, there is a default line cutting through the PRRPs. One camp is rather pro-NATO/pro-USA or anti-Russia, with four national parties: Lithuanian PTT, German AfD,30 Polish PiS and Dutch PVV. Another group’s leaning is rather anti-NATO/anti-US or pro-Russia, with four national parties as well: the Austrian FPÖ, Hungarian Jobbik, French FN and Italian LN. In other words: out of the eight national PRRPs that lay out their preferred geopolitical orientation, an equal number falls in two opposing camps.

Considering the main goal of the EU’s defence policy of a Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP), goal coherence would be achieved among the PRRPs, if one party did not instead opt for more common defence policy. The Austrian FPÖ argued at the party conference in 2013 that it would welcome it ‘if the EU strives for a self-reliant defence architecture that is independent of NATO and the USA’.31 This stands in stark contrast to the other PRRPs on the issue, as can be seen in the following quote from the Danish DF:

The Danish People’s Party is a supporter of Denmark upholding its freedom and sovereignty through membership in NATO and the UN … The Danish People’s Party is an opponent of the EU creating an independent defence. Attempts at cr...