![]()

1

Introduction to the 1980s

Sandra G. Shannon

Politics

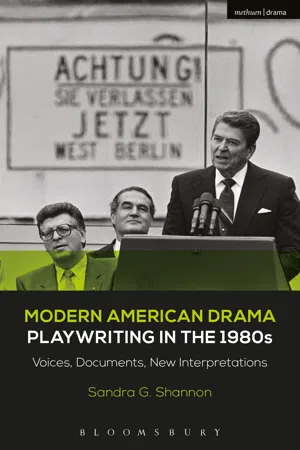

Ronald Reagan was the face of American-style politics during the 1980s. His rugged good looks, movie-star status and impressive way with words quickly made him a standout within the Republican Party. Reagan combined this charm with a conservative, no-nonsense leadership approach when it came to the safety and security of the United States and, lest foreign countries mistook his predecessor’s mistakes as indications of weakness, he let potential adversaries know that the US was not a country to mess with. Evidence that there was ‘a new sheriff in town’ came within minutes of Reagan’s inauguration: Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini released the American hostages who had been held captive in Iran for 444 days. Even though Carter had been in ongoing negotiations concerning the hostages’ release and terms of the release were in place, Reagan capitalized on the favorable public sentiments that followed the end of the crisis. An end to the hostage crisis also allowed him to focus on the struggling US economy during his first few months in office, rather than conflicts with Iran.

Reagan continued to capitalize on his growing tough-guy reputation as he negotiated on the world stage. According to a published report from the US State Department’s Office of the Historian,

The period 1981–1991 witnessed a dramatic transformation in the relationship between the United States and the Soviet Union. During these years the specter of a nuclear war between the superpowers receded as the Cold War ended swiftly, nearly entirely peacefully, and on US terms. When Ronald Reagan became president in January 1981, such outcomes were inconceivable. The Soviets had invaded Afghanistan, causing President Jimmy Carter to withdraw a strategic arms limitation treaty (SALT II) from Senate ratification, boycott the 1980 Olympics Games in Moscow, and ban U.S. grain sales to Moscow. Détente – or, ‘relaxation of tensions’ – yielded to confrontation.1

Clearly, the presidency of Ronald Reagan was transformative as he succeeded in restoring America’s image in the world as a formidable superpower, engaged in nuclear arm control talks and attempted to reverse the spread of communism in South America, Africa and South Asia. His nationalist efforts were not without setbacks, however. His introduction of the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) program in 1983 was given a cool reception by the Soviet Union, who—fearing that it would pose a threat—withdrew from setting a timetable for further talks. In an ironic reversal, the 1980s saw dramatic increases in the nuclear arms race, which culminated in 1991 at a level of more than ten thousand strategic warheads on both sides.

At the beginning of the 1980s, as the Cold War showed no signs of warming, arms control advocates argued for a ‘nuclear freeze’ agreement between the United States and the Soviet Union. In 1982, New York’s Central Park became the site of what was, arguably, the largest mass demonstration in American history in support of the freeze. Given this mandate, Reagan welcomed the March 1985 appointment of Mikhail Gorbachev as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. This fellow leader was both amenable to reason and willing to negotiate with Reagan on matters pertaining to nuclear arms control. A series of summits and high-profile meetings occurred between August and September 1986 followed by a meeting between President Reagan and General Secretary Gorbachev in Reykjavik, Iceland, in October 1986. Unfortunately, the Reykjavik summit talks broke down when Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev insisted that American research for the Strategic Defense Initiative, also known as “Star Wars,” be strictly confined to laboratories for ten years; Reagan refused.

In April 1987, the Soviet Union also proposed a freeze on shorter-range missile deployments and agreed, in principle, to intrusive on-site verification. Although previous major arms talks had collapsed at Reykjavik, Reagan would ultimately win over Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev in four summit conferences that yielded the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, an agreement that required the United States and the Soviet Union to eliminate and permanently abandon any aspirations for nuclear and conventional ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges of 500 to 5,500 kilometres.2 These actions accelerated the end of the Cold War (1989–91), which came with the collapse of communism both in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, and in numerous Third World countries.

The political landscape in America during the 1980s also included major domestic events apart from international affairs that topped President Reagan’s agenda. Issues that arose on the home front were varied and numerous – ranging from shifts in basic family dynamics to the rise of the populist conservative movement known as the New Right and diverse factions of America, such as evangelical Christians, anti-tax crusaders and advocates of deregulation and smaller markets.

Other political mavericks pushed for a more powerful American presence abroad in opposition to agendas espoused by disaffected white liberals and defenders of an unrestricted free market. According to the website U.S. History: Pre-Columbian to the New Millennium,

Not everyone was happy with the social changes brought forth in America in the 1960s and 1970s. When Roe vs. Wade guaranteed the right to an abortion, a fervent pro-life movement dedicated to protecting the ‘unborn child’ took root. Antifeminists rallied against the Equal Rights Amendment and the eroding traditional family unit. Many ordinary Americans were shocked by the sexual permissiveness found in films and magazines. Those who believed homosexuality was sinful lambasted the newly vocal gay rights movement. As the divorce and crime rates rose, an increasing number of Americans began to blame the liberal welfare establishment for social maladies. A cultural war unfolded at the end of the 1970s … Enter the New Right … a combination of Christian religious leaders, conservative business bigwigs who claimed that environmental and labor regulations were undermining the competitiveness of American firms in the global market, and fringe political groups.3

Chief among the New Righters was American media mogul, executive chairman and former Southern Baptist minister Pat Robertson, who generally supported conservative Christian ideals. Robertson was part of a new breed of ‘televangelists’ who rose to political and cultural prominence in the late 1970s and early 1980s. He used his television station, The Christian Broadcast Network, to deliver a conservative message to millions.4

Sociologists link the rise of this New Right to both population shifts and disaffection in the so-called ‘Sunbelt’, a mostly suburban and rural region that stretches from the Southeastern to Southwestern regions of the country, including states such as Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Mexico, South Carolina, Texas and roughly two-thirds of California. These areas have seen substantial population growth since the 1960s from an influx of people seeking a warm and sunny climate, a surge in retiring baby boomers and growing economic opportunities. Unfortunately, this surge is also accompanied by overcrowding, pollution and crime. Many among this demographic had migrated from the older industrial cities of the ‘Rust Belt’. Moreover, many were averse to paying high taxes for social programmes they did not consider effective and became sceptical of the stagnating economy. Many were also frustrated by what they saw as the federal government’s constant and unwarranted interference in their lives. The movement resonated with many citizens who had once supported more liberal policies but who no longer believed the Democratic Party represented their interests.

The economy

Like so many other administrations, matters pertaining to war and the state of the economy could determine their legacy. Initially, President Reagan inherited an economy mired in stagnant economic growth, high unemployment and high inflation. Stagnation, as it was called, was brought on by a combination of double-digit economic contraction with double-digit inflation. At the outset of his first term as president in 1981, Reagan set in motion a host of unprecedented economic initiatives that resulted in significant reductions in inflation and annual growth of GDP. He went to work instituting expansionary fiscal policies to stimulate the American economy. He introduced measures to deregulate the oil industry that had the unfortunate byproduct of the 1980s oil glut. The economy was in recession in 1981–3, but recovered and grew sharply after that. From implementing widespread tax cuts and deregulating domestic markets to decreasing social spending while increasing military budgets, Reagan left his mark. In his suggestively titled study, ‘Ronald Reagan: Worst President Ever?’, Robert Parry writes:

The American Dream also dimmed during Reagan’s tenure. While he played the role of the nation’s kindly grandfather, his operatives divided the American people, using ‘wedge issues’ to deepen grievances especially of white men who were encouraged to see themselves as victims of ‘reverse discrimination’ and ‘political correctness.’ Yet even as working-class white men were rallying to the Republican banner (as so-called ‘Reagan Democrats’), their economic interests were being savaged. Unions were broken and marginalized; ‘Free trade’ policies shipped manufacturing jobs abroad; old neighborhoods were decaying; drug use among the young was soaring. Meanwhile, unprecedented greed was unleashed on Wall Street, fraying old-fashioned bonds between company owners and employees. Before Reagan, corporate CEOs earned less than 50 times the salary of an average worker. By the end of the Reagan–Bush-I administrations in 1993, the average CEO salary was more than 100 times that of a typical worker. (At the end of the Bush-II administration, that CEO-salary figure was more than 250 times that of an average worker.)5

A major component of the Reagan administration’s economic plan was based upon the theory of supply-side economics, which advocated reducing tax rates so, in theory, people could keep more of what they earned. They espoused that lower tax rates would induce people to work harder and longer, and that this, in turn, would lead to more saving and investment, which, also in turn, would result in more production and stimulate overall economic growth. While the Reagan-inspired tax cuts served mainly to benefit wealthier Americans, the economic theory behind the cuts argued that benefits would extend to lower-income people as well because higher investment would lead to new job opportunities and higher wages. Republicans quickly adopted this moratorium on taxes as a major part of their party’s platform and, at every turn, held it over the heads of their ‘tax and spend’ Democratic rivals.

A competing central theme of Reagan’s national agenda, however, was his belief that the federal government had become too big and intrusive. In the early 1980s, while he was cutting taxes, Reagan was also slashing social programmes. He also undertook a campaign throughout his tenure to reduce or eliminate government regulations affecting the consumer, the workplace and the environment. At the same time, however, he feared that the United States had neglected its military in the wake of the Vietnam War, so he successfully pushed for big increases in defence spending.

The combination of tax cuts and higher military spending overwhelmed more modest reductions in spending on domestic programmes. As a result, the federal budget deficit swelled even beyond the levels it had reached during the recession of the early 1980s. From $74 million in 1980, the federal budget deficit rose to $221 million in 1986. It fell back to $150 million in 1987, but then started growing again. Some economists worried that heavy spending and borrowing by the federal government would reignite inflation, but the Federal Reserve remained vigilant about controlling price increases, moving quickly to raise interest rates any time it seemed a threat. Under chairman Paul Volcker and his successor, Alan Greenspan, the Federal Reserve retained the central role of economic traffic cop, eclipsing Congress and the president in guiding the nation›s economy.6

By 1983, the economy had rebounded and the United States entered into one of the longest periods of sustained economic growth since the Second World War. The annual inflation rate remained under 5 per cent from 1983 through to 1987. Still, serious problems remained. Farmers’ problems continued; their suffering was compounded by serious droughts in 1986 and 1988. Federal deficits soared throughout the 1980s. From $74 billion in 1980, the federal budget deficit rose to $221 billion in 1986 before falling back to $150 billion in 1987. The US trade deficit hit a record $152 billion that same year. A stock market crash in the autumn of 1987 led many to question the stability of the economy. In fact, the US economy slowed and dipped into recession in 1991 but began a slow recovery in 1992.7

As a result of the slowing economy and other factors, the federal budget deficit began heading upward again. Although the stock market recovered, the financial industry was particularly plagued with problems. Numerous savings institutions as well as some banks and insurance companies either faltered or completely collapsed – in many instances, necessitating federal government takeover. Well into the 1990s, credit market and other problems lingered on. By contrast, other sectors of the economy, such as computers, aerospace and export industries generally showed signs of continuing growth.8

Domestic life

The 1980s saw the advent of the so-called ‘New Man’, which was a radical way to describe a male who wholeheartedly accepts equality in domestic life and who believes that women and men are equal and should be free to do the same things, such as share her household workload, show so-called ‘feminine’ sensitivity and advocate equal pay for equal work. For some people, the new man represented a shift to an emotionally and domestically involved man who was more nurturing and pro-feminist; for others, he was an individualistic and narcissistic man who spent as much on beauty products and who needed just as much time applying them as women did.

The significant numbers among men who took on household chores, tended to children and performed a host of other roles originally ascribed to women increased exponentially in the 1980s as wives, sisters, mothers and daughters traded the home front for the office. With increasing numbers of women enteri...