![]()

PART I

NORWAY

![]()

CHAPTER 1

NORWAY’S APPROACH TO THE ARCTIC: POLICIES AND DISCOURSE

Geir Hønneland and Leif Christian Jensen

Introduction

Arctic affairs are an integral part of Norway’s foreign policy. The strength of this component in Norwegian foreign policy has varied over time, as has its profile and formal designation. In general, the term ‘Arctic’ is rarely used in Norwegian foreign policy discourse, and then only in reference to something farther off in either time (like polar explorations before the Second World War) or space (outside Norway’s immediate sphere of interest, such as the North Pole area or the American Arctic). ‘The North’ (in Norwegian: nord) or ‘the northern regions’ (in Norwegian: nordområdene) have been the preferred terms for describing practical foreign politics in the European Arctic. In practice, Norway’s northern foreign policy is mainly about relations with other states in the Barents Sea region (see Figure 1.1). Of particular importance are relations with Russia.

This chapter discusses the evolvement of contemporary Norwegian High North policies, with particular emphasis on the first decade of the twenty-first century. In the first part of the chapter, we argue that these policies consist of layers from different time periods, ranging from the Cold War with its East–West tensions, to the immediate post-Cold War years when new institutional partnerships were established between Norway and Russia in the High North, and the years from around 2005, characterized by functional and geographical dispersion of Norwegian High North politics. In the second part of the chapter, we analyze Norwegian public discourse on the High North. We pay special attention to how the prevailing discourses reflected (and possibly spurred) the transition from one phase to another: why did the mounting fatigue that surrounded the institutional collaboration with Russia in the early 2000s transform into a new euphoria?

Norwegian High North Policies

With the end of the Cold War, reference to ‘the north’ in Norwegian foreign policy discourse almost disappeared, since it smacked of Cold War tensions or even of Norway’s earlier reputation as an expansionist polar nation. Norway was now building up a reputation as a ‘peace nation’, heavily involved in mediating peace in various southern corners of the world. This did not mean that Norwegian foreign politics in the European Arctic no longer existed – only that the main focus was now on institutional cooperation with Russia, referred to as ‘strategies towards Russia’, or ‘neighbourhood policies’. In the mid-2000s, ‘the northern regions’ (nordområdene, with ‘the High North’ as the official English translation) were again explicitly defined as the number one priority of Norwegian foreign policy. Although this happened to coincide with the international buzz about a ‘rush for the Arctic’, it can largely be explained, as will be shown later, by internal issues in Norwegian politics, and in the country’s relationship with Russia. Above all, this new northern policy has seen the disappearance of the division between foreign and internal politics. While it encompasses both traditional security politics in the European Arctic and the ‘softer’ institutional collaboration with Russia initiated in the 1990s, many see Norway’s ‘new’ northern policies as mainly an instrument for further developing business and science in the country’s northern regions.

The Cold War legacy: Security, jurisdiction and fisheries management

The Northern Fleet, established on the Kola Peninsula in 1933, remained the smallest of the four Soviet naval fleets until the 1950s, when a period of expansion set in. By then, the Soviet Union had entered the nuclear age: the country’s first nuclear submarine was stationed on the Kola Peninsula in 1958, at Zapadnaya Litsa, close to the border with Norway. Six new naval bases for nuclear submarines were built, as well as several smaller bases for other vessels. By the late 1960s, the Northern Fleet ranked as the largest of the Soviet fleets.

In this situation, Norway chose the combined strategy of deterrence and reassurance. Deterrence was secured through NATO membership and by maintaining the Norwegian armed forces at a level deemed necessary to hold back a possible Soviet attack until assistance could arrive from other NATO countries. So that the Soviets should not misinterpret activities on the Norwegian side as aggressive, Norway placed a number of self-imposed restrictions upon itself. Notably, other NATO countries were not allowed to participate in military exercises east of the 24th parallel, which runs slightly west of the middle of Norway’s northernmost county, Finnmark. The border between Norway and the Soviet Union was peaceful, but strictly guarded; there was no conflict, but there was also little interaction.

Besides regular diplomatic contact, management of the abundant fish resources of the Barents Sea was an area of particular joint interest for Norway and the Soviet Union. From the late 1960s, the two countries had informally discussed the possibilities of bilateral management measures. A window of opportunity came with the drastic changes in the law of the sea that were implemented in the mid-1970s. The principle of 200-mile exclusive economic zones (EEZs) was adopted at the third UN Conference on the Law of the Sea in 1975. The right and responsibility to manage marine resources within 200 nautical miles of shore was thus transferred to the coastal states at this time. When Soviet Minister of Fisheries Aleksandr Ishkov visited Oslo in December 1974, the two countries agreed to establish a joint fisheries management arrangement for the Barents Sea.1 The agreement established the Joint Norwegian–Soviet (now Norwegian–Russian) Fisheries Commission, to meet at least once every year, alternately on each party’s territory. When the first session took place in January 1976, the parties had agreed to jointly manage the two most important fish stocks in the area, cod and haddock, sharing the quotas 50–50. In 1978, they agreed to treat capelin as a shared stock, and split the quota 60–40 in Norway’s favour.

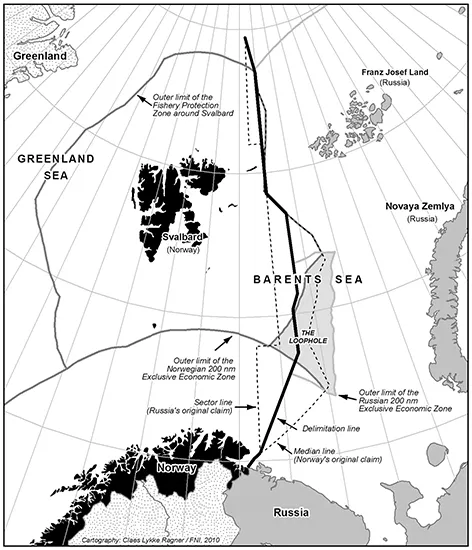

Both Norway and the Soviet Union established their EEZs in 1977 (see Figure 1.1). However, the two states could not agree on the principle for drawing the delimitation line between their respective zones. They had been negotiating the delimitation of the Barents Sea continental shelf since the early 1970s, and the division of the EEZs was brought into these discussions. The two parties had agreed to use the 1958 Convention on the Continental Shelf as a basis. According to this convention, continental shelves may be divided between states if so agreed. If agreement is not reached, the median line from the mainland border shall normally determine the delimitation line, but special circumstances may warrant adjustments. In the Barents Sea, Norway adhered to the median-line principle, whereas the Soviet Union claimed the sector-line principle, according to which the line of delimitation would run along the longitude line from the tip of the mainland border to the North Pole. The Soviets held out for the sector-line principle, having claimed sector-line limits to Soviet Arctic waters as early as 1928. Moreover, they argued that in the Barents Sea special circumstances – notably the size of the Soviet population in the area, and the strategic significance of this region – warranted deviation from the median line.

In 1978, a temporary Grey Zone agreement was reached, to avoid unregulated fishing in the disputed area.2 This agreement required Norway and the Soviet Union to regulate and control their own fishers and third-country fishers licensed by either of them, and to refrain from interfering with the activities of the other party’s vessels, or vessels licensed by them. The arrangement was explicitly temporary and subject to annual renewal. The Grey Zone functioned well for the purposes of fisheries management, but the prospect of underground hydrocarbon resources in the area pressed the parties to a final delimitation agreement, which was reached in spring 2010.3 The agreement is a compromise, with the delimitation line midway between the median line and the sector line.

Figure 1.1 Jurisdiction of the Barents Sea.4

Another area of contention is the Fishery Protection Zone around Svalbard. Norway claims the right to establish an EEZ around the archipelago, but has so far refrained from doing so because the other signatories to the 1920 Svalbard Treaty have signalled that they would not accept such a move.5 The Svalbard Treaty gave Norway sovereignty over the archipelago, which had been a no man’s land in the European Arctic. However, the treaty contains several limitations on Norway’s right to exercise this jurisdiction. Most importantly, all signatory powers enjoy equal rights to let their citizens extract natural resources on Svalbard. Further, the archipelago is not to be used for military purposes, and there are restrictions on Norway’s right to impose taxes on the residents of Svalbard. The original signatories were Denmark, France, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, the UK and the USA. The Soviet Union joined in 1935.

The other signatories (other than Norway) hold that the non-discriminatory code of the Svalbard Treaty must also apply to the ocean area around the archipelago,6 whereas Norway refers to the treaty text, which deals only with the land and territorial waters of Svalbard. The waters around Svalbard are important feeding grounds for juvenile cod, and the Protection Zone, determined in 1977, represents a ‘middle course’ aimed at securing the young fish from unregulated fishing. However, the zone is not recognized by any of the other states that have had quotas in the area since the introduction of the EEZs. To avoid provoking other states, Norway refrained for many years from penalizing violators in the Svalbard Zone. Force was used for the first time in 1993, when Icelandic trawlers and Faroese vessels under flags of convenience – neither with a quota in the Barents Sea – started fishing there. The Norwegian Coast Guard fired warning shots at the ships, which then left the zone. The following year, an Icelandic fishing vessel was the first to be arrested for fishing in the Svalbard Zone without a quota.

Soviet/Russian vessels have been fishing in the Svalbard Zone regularly since its establishment – indeed, they represent the majority of fishing operations in the area. They do not report their catches in the area to Norwegian authorities, and Russian captains consistently refuse to sign inspection forms presented by the Norwegian Coast Guard. But they welcome Norwegian inspectors on board, and the same inspection procedures are pursued in the Svalbard Zone as in the Norwegian EEZ.

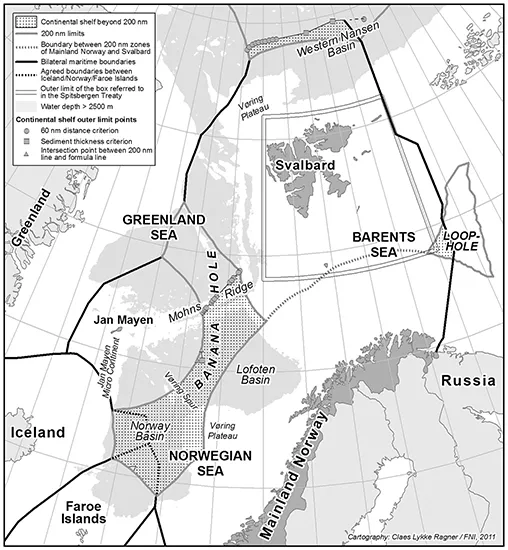

In 2009, the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf approved the Norwegian submission, confirming the existence of a Norwegian shelf beyond 200 nautical miles in three places: the Western Nansen Basin north of Svalbard, in parts of the ‘Loophole’ in the east, and the ‘Banana Hole’ in the south-west (see Figure 1.2).7

Figure 1.2 Barents Sea continental shelf.8

The legacy of the 1990s: Institutional collaboration with Russia

Norway’s foreign policy in the European Arctic during the 1990s was mainly concerned with bringing Russia into collaborative networks. The idea of a ‘Barents region’ was first aired by Norwegian Minister of Foreign Affairs Thorvald Stoltenberg in April 1992. After consulting with Russia and the other Nordic states, the Barents Euro-Arctic Region (BEAR) was established by the Kirkenes Declaration of January 1993, whereby Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia pledged to work together at both regional and national levels.9 At the regional level, the BEAR initially included the three northernmost counties of Norway, together with Norrbotten in Sweden, Lapland in Finland, Murmansk and Arkhangelsk Oblasts and the Republic of Karelia in Russia (see Figure 1.3). They were joined in 1997 by Nenets Autonomous Okrug, located within Arkhangelsk Oblast, which became a member in its own right, and later by Västerbotten (Sweden), Oulu and Kainuu (Finland) and the Republic of Komi (Russia). A...