- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

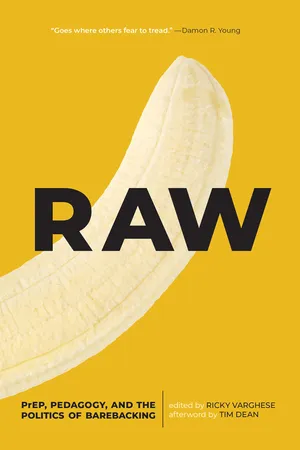

Marking the tenth anniversary of Tim Dean's Unlimited Intimacy, Raw returns to the question of sex without condoms, or barebacking, a timely topic in the age of PrEP, a drug that virtually eliminates the transmission of HIV."Essential reading for anyone interested in the politics of sex, sexuality and sexual representation in the 21st century." —John Mercer, author ofGay Pornography"Finally, queer theory returns to a topic it has had surprisingly little to say about: sex! Underpinning these essays is a thrilling wager: that desire demands discourse but resists rationalization." —Damon R. Young, author ofMaking Sex Public and Other Cinematic Fantasies"A major contribution to research. It opens up the discourse on barebacking to a varity of perspectives and theoretical arguments, and makes clear that the topic remains relevant." —John Paul Ricco, author ofThe Decision Between Us"Rawprovides an account of the state of queer-theoretical scholarship on bareback today, and makes a pluralising and distinctive contribution to that body of work, significantly broadening this field of scholarship." —Oliver Davis, editor ofBareback Sex and Queer Theory across Three National Contexts (France, UK, US)Contributors: Jonathan A. Allan (Brandon University), Tim Dean (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign), Elliot Evans (University of Birmingham), Christien Garcia (University of Cambridge), Octavio R. Gonzales (Wellesley College), Adam J. Greteman (School of the Art Institute of Chicago), Frank G. Karioris (University of Pittsburgh & American University of Central Asia), Gareth Longstaff (Newcastle University), Paul Morris (San Francisco), Susanna Paasonen (University of Turku), Diego Semerene (Oxford Brookes University), Evangelos Tziallas (Concordia University), Ricky Varghese (Toronto), Rinaldo Walcott (University of Toronto)

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Table of contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Bio-political Limits

- Chapter 1

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Bodily Limits

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Porno-graphic Limits

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Psycho-analytic and Peda-gogical Limits

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Afterword

- About the Contributors