WHY THE NEW TESTAMENT?

Why should anyone spend time studying the contents of the New Testament? Why invest so much time in a relatively small collection of Greek texts? More precisely, exactly what is the New Testament for and what does that tell us about how we should study it?

I (N. T. Wright, henceforth NTW) own many different kinds of books. I have a lot of history books, and I love to find out more and more not only about what happened in the past but what it was like being there and the ways in which people thought and felt. I want to know what motivated them. I have a good many novels and books of short stories, and though they don’t describe things that actually happened they encourage me to think about why people behave the way they do, not least why they get into the messes they do and what might be done about it. I even have quite a few books of plays—Shakespeare of course, but lots of others too: I enjoy the theatre, and if you let your imagination loose you can read the play at home and see it going on in your mind’s eye. It would be quite different, of course, if I knew I was going to be acting in a play: I would be reading it not just to learn my lines but to think into the different characters and get a sense of what it would be like to ‘be’ the person I’d be playing, and how I would relate to the others.

So we could go on, with poetry high on the list as well, and biography too. But there are plenty of quite different books which are really important to me. I have several atlases, partly for when I’m planning travel but also because I’m fascinated by the way different parts of the world relate to one another. Since my work involves different languages, I have several dictionaries which I use quite a lot. I enjoy golf, even though I’m not much good at it; I have quite a few books about the game, and how to play it better. I read these books but don’t usually manage to obey them, or not thoroughly. I have a couple of books on car maintenance, a few books about how to make your garden look better, first-aid books for health emergencies, and so on.

Where do we fit the New Testament into all that? For some people, it seems to function at the level of car maintenance or garden tips, or even first-aid: it’s a book to turn to when you need to know about a particular issue or problem. (‘What does the Bible teach about x, y, or z?’) For some, it’s like a dictionary: a list of all the things you’re supposed to know and believe about the Christian faith, or an atlas, helping you to find your way around the world without getting lost. This is what some people mean when they speak of the Bible being the ultimate ‘authority’, and so they study it as you might study a dictionary or atlas, or even a car manual.

Now that’s not a bad thing. Perhaps it’s better to start there than nowhere at all. But the puzzle is that the New Testament really doesn’t look like that kind of book. If we assume, as I do, that the reason we have the New Testament the way it is is that this is what God wanted us to have—that this is what, by the strange promptings of the holy spirit, God enabled people like Paul and Luke and John and the others to write—then we should pay more attention to what it might mean that this sort of a book—or rather these sorts of books, because of course the New Testament contains many quite different books—is the one we’ve been given. Only when we do that will we really be living under its ‘authority’, discovering what that means in practice.

When we rub our eyes and think about this further, we discover that the New Testament includes all those other kinds of books as well: history, short stories which didn’t happen but which open up new worlds (I’m thinking of the parables of Jesus in particular), biography, poetry, and much besides. And though none of the New Testament is written in the form of a play to be acted on stage, there is a strong sense in which that is precisely what it is.

Or rather, it’s part of a play, the much larger play which consists of the whole Bible. The biblical drama is the heaven-and-earth story, the story of God and the world, of creation and covenant, of creation spoiled and covenant broken and then of covenant renewed and creation restored. The New Testament is the book where all this comes in to land, and it lands in the form of an invitation: this can be and should be your story, my story, the story which makes sense of us, which restores us to sense after the nonsense of our lives, the story which breathes hope into a world of chaos, and love into cold hearts and lives. The New Testament involves history, because it’s the true story of Jesus and his first followers. It includes poetry, because there are some vital things you can only say that way. It contains biography, because the key to God’s purposes has always been the humans who bear his image, and ultimately the One True Human who perfectly reflects his Image, Jesus himself. And yes, there are some bits which you can use like a dictionary or a car manual or a how-to-play-golf kind of book. But these mean what they mean, and function best as a result, within the larger whole. And when we study the New Testament it’s the larger whole that ought to be our primary consideration.

So how do we fit into that larger whole? How do we understand the play, the real-life story of God and the world which reached its ultimate climax in Jesus of Nazareth and which then flows out, in the power of the spirit, to transform the world with his love and justice? How do we find our own parts and learn to play them? How do we let the poetry of the early Christians, whether it’s the short and dense poems we find in Paul or the extended fantasy-literature of the book of Revelation, transform our imaginations so we can start to think in new ways about God and the world, about the powers that still threaten darkness and death, and about our role in implementing the victory of Jesus?

One central answer is that we must learn to study the New Testament for all it’s worth, and that’s what this whole book is designed to help us do. Jesus insisted that we should love God with our minds, as well as our hearts, our souls, and our strength. Devotion matters, but it needs direction; energy matters, but it needs information. That’s why, in the early church, one of the most important tasks was teaching. Indeed, the Christian church has led the way for two thousand years in making education in general, and biblical education in particular, available to people of all sorts. A good many of the early Christians were functionally illiterate, and part of the glory of the gospel then and now is that it was and is for everyone. There shouldn’t be an elite who ‘get it’ while everybody else is simply going along with the flow. So Jesus’ first followers taught people to read so that they could be fully conscious of the part they were to play in the drama. That’s why the New Testament was and is for everyone.

By contrast with most of the ancient world, early Christianity was very much a bookish culture. We sometimes think of the movement as basically a ‘religion’; but a first-century observer, blundering in on a meeting of Christians, would almost certainly have seen them initially as belonging to some kind of educational institution. This is the more remarkable in that education in that world was mostly reserved for the rich, for the elite.

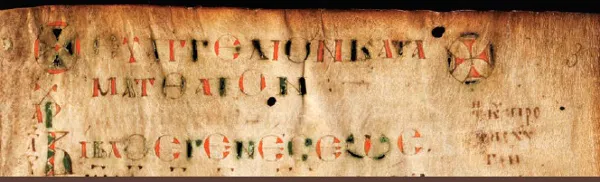

What’s more, Jesus’ first followers were at the forefront of a new kind of textual technology. From quite early on they used the codex, with sheets stuck together to comprise something like a modern book, rather than the scroll, which couldn’t hold nearly so much and which was hard to use if you wanted to look up particular passages. In fact...