![]()

1

Nathan Davis at Carthage

Friends at dinner

In the spring of 1858 the Reverend Nathan Davis hosted a distinguished group to Sunday dinner. Two of his guests were to achieve lasting renown, but Davis himself is almost unknown, although he, too, was a remarkable person. Born in London, Davis was a Jewish convert to Christianity, a former Protestant missionary at Tunis, an expert on Tunisia with complete fluency in Arabic, and the personal friend of the Bey. He had at this moment been funded by the British Foreign Office for more than a year to excavate at Carthage. He had already shipped home the remains of a fine Roman mosaic and had packaged up many other mosaics and finds for transport. Davis’ dinner was held just over ten miles north-east of Tunis at a villa in the isolated and tiny oasis village of Gammarth on the shores of the Mediterranean. Davis had recently moved his family there to be closer to his new excavations north of Carthage, in the ancient necropolis of Gammarth and at Roman villas along the coast.

Among those Davis had invited to dinner was the novelist Gustave Flaubert, who had ridden out from Tunis for the occasion (Fig. 1.1). Flaubert had recently arrived from France to absorb impressions for the novel he was planning on Punic Carthage. This would be a significant day for Flaubert’s novel-to-be. Feeling excluded from the English conversation, he used the occasion to observe Mrs Davis’ young lady companion, Nelly Rosenberg, who would become the physical model for his Punic heroine, Salammbô. The elderly Lady Franklin, the former first lady of Van Diemen’s Land and wife of Sir John Franklin, leader of a lost Arctic expedition, was also present, accompanied by her niece and devoted companion, Sophia Cracroft. The two women had been rescued from an unsuitable hotel in Tunis by the Davises, and invited to stay with them at Gammarth.

The intelligent and outspoken Lady Franklin would have taken a leading role in the conversation. Her listeners included Captain Edwin Porcher (Fig. 1.2), who had instructions to put his ship HMS Harpy at the service of Reverend Davis. Before the recent arrival of Captain Porcher, Davis had been planning to investigate archaeological sites on Cap Bon, and it may have been this day’s conversation that turned Davis’ interest in a completely different direction, to the nearby Roman city of Utica, where much of this group proceeded a few days later. The meeting of Davis and Porcher had a further significance for Mediterranean archaeology, for Porcher was soon involved in his own excavations at Cyrene.

David Porter Heap, a young American medical doctor who was the son of the former long-time U.S. consul at Tunis, was also present with his wife Elizabeth. Heap was positioning himself for a future consular posting, but in the meantime Davis had recruited the young doctor to work with him on his excavations. The Heap family occupied the Davises’ former home and workshed on the ruins of Carthage, about four miles to the south. The Davises and the Heaps had a total of six or seven young children, and some of them were certainly running about the scene.

Davis’ archaeological excavations at Carthage were arousing widespread interest, and he had had European visitors before. Nevertheless the guests at this dinner, with their various roles and preoccupations, formed a microcosm of the colonialist enterprise. Today we see Davis primarily as an archaeologist, and identify him with the intellectual and ‘scientific’ side of his venture. Certainly his status in this group was at least partly determined by what his contemporaries saw as his scientific role, but Davis was also an energetic and enterprising man with heavy financial obligations and a family to support, who had found a field for his many talents in Tunisia. Davis and his European contemporaries led their lives in a context in which exploiting, reforming and eventually governing the colonial world was closely linked to the appropriation of its art and culture. This was as true for Davis’ archaeological forerunners and contemporaries as it was for Davis, and the question of who benefits economically, politically and culturally from archaeology is still relevant today.

A mystery in the British Museum

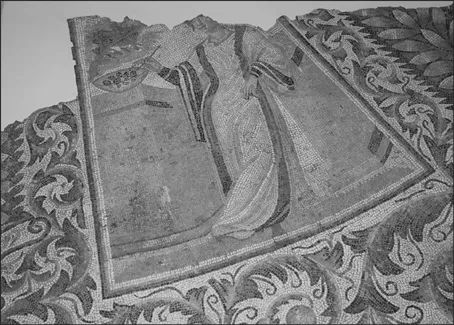

Today visitors to the British Museum can see a spectacular collection of Roman polychrome mosaics in the north-west stairwell, many of which were lifted at Carthage by Davis between 1856 and 1859. In a three-year campaign funded by the British Foreign Office, Davis excavated twenty-eight individual Roman mosaics at Carthage, lifted twenty-six (plus five more from Utica) and sent them to the Museum on British naval vessels. These mosaics date from the late first to the mid-sixth century AD. The most important for the history of Roman art is the first mosaic Davis lifted, the Mosaic of the Months and Seasons (Fig. 1.3), but the group as a whole has great value as a representative sample of Roman mosaics at Carthage.

When I first saw these mosaics, I was taken aback by the disparity between the impressiveness and number of these finds, and the fact that Davis’ excavations at Carthage were almost unknown to the many archaeologists, including myself, who worked at Carthage in the later twentieth century. I had read and enjoyed Davis’ book on his excavations at Carthage, but Davis hardly gave the impression in that account that he had sent the British Museum significant archaeological finds. I found myself asking questions that had no obvious answers. How did it happen that so many once permanently installed and essentially fragile Roman mosaic floors were lifted and shipped to England, despite the fact that they were large, extremely heavy, and generally impractical to manage? What were the motivations behind these exploits? How did this happen at a time when archaeology as a science was as yet unborn? What were the original contexts of these mosaics? Was there contemporary documentation of the excavations and the objects discovered? I realized that if the Museum had these mosaics on display, they must also have records of their acquisition, and I began research on Davis and his finds. As I followed up very disparate clues, I was eventually able to reconstruct an account of Davis’ excavations. This book is the result. It is Davis’ story, but it is also the story of his colleagues and rivals in the earliest archaeological excavations at Carthage.

Carthage in its Mediterranean context

Today Tunisia is a small country with a long Mediterranean coastline. It lies in the middle of the north coast of Africa, opposite Sicily and Italy. Here the Phoenicians founded the trading settlement of Carthage, according to tradition in 814 BC. The port city of Carthage eventually controlled an empire in the western Mediterranean, but the jealousy of Rome led to three Punic Wars and the destruction of Carthage in 146 BC. Because Carthage was an ideal port site, it was re-founded as a Roman colony by 29 BC, if not a little earlier. The city again became rich, with high points of prosperity in the second and fourth centuries AD. In AD 439, Carthage was captured by the Vandals, a Germanic tribe that controlled large areas of North Africa until the Byzantine reconquest of North Africa under Justinian in 534. Carthage then had another century as a Byzantine city before it was taken by the Arabs and finally sacked in 698. Gradually Tunis, which lay fifteen kilometers to the west, inland from the Mediterranean on the west side of the Lake of Tunis, became an important population centre. Particularly after Tunis became the Arab capital in 894, the site of Carthage was used as a quarry for Arab and European building projects, and these depredations continued for a thousand years.

In the nineteenth century, Carthage was part of the territory of Tunis. The Bey of Tunis, theoretically the regent of the Ottoman Sultan, ruled the area that today forms the country of Tunisia. The earliest attempts at archaeology in Carthage lie between two crucial dates: the first was the British Lord Exmouth’s bombardment of Algiers in 1816 and the second the French occupation of Tunisia in 1881. In this period European interference with the ‘Barbary States’ of North Africa rapidly progressed to conquest. The Regency of Tunis was tiny when compared to the territory of Algiers to the west and Tripoli to the east. It was also a poor and poorly-governed land, with a drastically falling population and a declining economy, but the brief reign of Mohammed Bey, Davis’ personal friend, would seem bright in contrast to the series of economic and political disasters that overtook Tunisia from the 1860s.

The Crimean war had ended in March of 1856. Britain and France had supported the Ottoman Empire against Russia and in return wanted liberalization and guarantees of human rights, to facilitate European commercial ventures. The French, who had controlled neighbouring Algeria since 1830, saw Tunisia as a potential colony, while the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Clarendon, aimed to stabilize the regime of Mohammed Bey, who was not a strong personality, by urging him to honour his ties to the Ottoman Sultan. Clarendon also hoped to strengthen British prestige in Tunis in relation to the French.

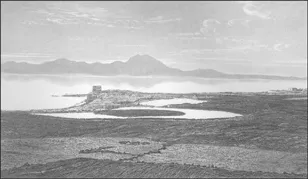

By the time Davis began to dig at Carthage, the site had already suffered the depredations of centuries, and all the great buildings of cut stone had been, one by one, dismantled and removed. Yet the desolation apparent on the surface (Fig. 1.4) was not so different from many untouched ancient sites (compare Fig. 1.5, today). For his part, the Danish consul, Christian Falbe, who drew a plan in the early 1830s that provided more knowledge of the ancient city than many years of archaeological exploration (Fig. 3.2), did not see or map intact structures, but only the core of concrete and rubble walls left behind when the stone facing had been removed.

In the course of his generally frustrating first months of excavation, Davis discovered that the poor raped site of Carthage still had one intact treasure to offer: its mosaics. Roman mosaics were almost certainly not what the British Museum was looking for. Nevertheless, Davis’ agreement with the Foreign Office required him to bring home artefacts, and therefore he devised a method to lift mosaics, and sent them to the Museum on ships of the British navy.

Archaeology at Carthage in its wider historical perspective

Archaeologists working at Carthage have only rarely had a strong historical understanding of previous work. There is no unified overview of what is now nearly two centuries of excavation. Furthermore, at a number of historical moments the work of earlier archaeologists has been ignored or discounted. The establishment of the French Protectorate in 1881 put an end to the first period of international adventure (the subject of this book) and privileged the work of French scholars, whether missionaries or part of the professional establishment. After the death in 1932 of Father Alfred-Louis Delattre, his fifty years of archaeological work at Carthage were often disregarded, largely because of his perceived lack of professional status. Tunisian independence in 1956 brought a break in the French traditions and staffing of the archaeological service. Finally, the beginning of the UNESCO ‘Save Carthage’ campaign in 1972 introduced a period of comparatively sophisticated methodology, but the European and North American scholars and students who came to Carthage in great numbers in the last quarter of the twentieth century often knew little or nothing of its long archaeological history.

Before the Danish consul, Christian Falbe, created an accurate topographical plan of the peninsula (Fig. 3.2),1 the site of Carthage was essentially incomprehensible. Because ancient Carthage is actually two superimposed cities with a history between them of more than fifteen hundred years, nineteenth-century archaeologists faced a three-dimensional puzzle. The site was enormous, covering a minimum of a square mile (260 ha) and with a typical depth of twenty-five feet (7.60 m) of soil. Furthermore, there was little guidance as to a best starting point. The plan of Falbe was published in 1833 and galvanized the French scholar Dureau de la Malle,2, because it revealed the outline of the circus, the amphitheatre and two enormous cisterns, typical remains of a Roman city. Falbe’s topographical map has the same fundamental importance for archaeology at Carthage as survey has for archaeological sites today.

Dureau de la Malle immediately interpreted the structures of Falbe’s plan in terms of Punic and Roman structures mentioned in the ancient texts. Most obviously, the low-lying ‘lagoons’ which Falbe identified as the ports agreed with the ancient description of the Punic circular naval harbour and the rectangular merchant harbour at Carthage during the Third Punic War. Falbe and Dureau de la Malle agreed that the highest hill in the centre of the city was therefore the Byrsa, the traditional name for the Punic acropolis, and that the Punic forum (generally regarded as a Roman rather than a Punic concept – an open public area including markets and civic buildings) lay between the ports and the Byrsa. Their identification of the location of the ports and the Byrsa has stood the test of time, but their propositions have been tested hard, because later scholars have repeatedly interpreted the site in a very different way.

The earliest period of archaeology at Carthage provided the underpinnings for everything that we know today about the material culture of the Punic and Roman cities. The beginnings of archaeology at Carthage date to the first tentative excavations of the Dutch engineer Jean Emile Humbert in 1817, followed by his excavations for the Museum of Leiden in 1822 and 1824. A limited and abortive personal effort of Danish consul Falbe in 1824 was followed by excavations funded by the Paris-based Society for the Exploration of Carthage, and was carried out by Falbe and his British colleague Sir Grenville Temple in 1838. Falbe and Temple based their work directly on Falbe’s experiences in preparing his plan. In open competition with Falbe and Temple, the British consul Sir Thomas Reade sp...