eBook - ePub

The Washingtons of Wessyngton Plantation

Stories of My Family's Journey to Freedom

- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Washingtons of Wessyngton Plantation

Stories of My Family's Journey to Freedom

About this book

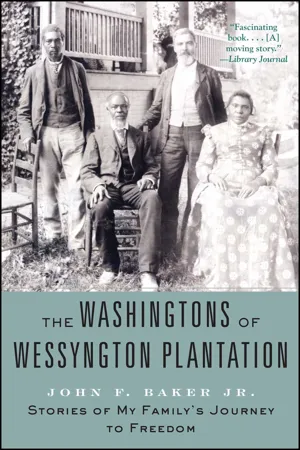

When John F. Baker Jr. was in the seventh grade, he saw a photograph of four former slaves in his social studies textbook—two of them were his grandmother's grandparents. He began the lifelong research project that would become The Washingtons of Wessyngton Plantation, the fruit of more than thirty years of archival and field research and DNA testing spanning 250 years.

A descendant of Wessyngton slaves, Baker has written the most accessible and exciting work of African American history since Roots. He has not only written his own family's story but included the history of hundreds of slaves and their descendants now numbering in the thousands throughout the United States. More than one hundred rare photographs and portraits of African Americans who were slaves on the plantation bring this compelling American history to life.

Founded in 1796 by Joseph Washington, a distant cousin of America's first president, Wessyngton Plantation covered 15,000 acres and held 274 slaves, whose labor made it the largest tobacco plantation in America. Atypically, the Washingtons sold only two slaves, so the slave families remained intact for generations. Many of their descendants still reside in the area surrounding the plantation. The Washington family owned the plantation until 1983; their family papers, housed at the Tennessee State Library and Archives, include birth registers from 1795 to 1860, letters, diaries, and more. Baker also conducted dozens of interviews—three of his subjects were more than one hundred years old—and discovered caches of historic photographs and paintings.

A groundbreaking work of history and a deeply personal journey of discovery, The Washingtons of Wessyngton Plantation is an uplifting story of survival and family that gives fresh insight into the institution of slavery and its ongoing legacy today.

A descendant of Wessyngton slaves, Baker has written the most accessible and exciting work of African American history since Roots. He has not only written his own family's story but included the history of hundreds of slaves and their descendants now numbering in the thousands throughout the United States. More than one hundred rare photographs and portraits of African Americans who were slaves on the plantation bring this compelling American history to life.

Founded in 1796 by Joseph Washington, a distant cousin of America's first president, Wessyngton Plantation covered 15,000 acres and held 274 slaves, whose labor made it the largest tobacco plantation in America. Atypically, the Washingtons sold only two slaves, so the slave families remained intact for generations. Many of their descendants still reside in the area surrounding the plantation. The Washington family owned the plantation until 1983; their family papers, housed at the Tennessee State Library and Archives, include birth registers from 1795 to 1860, letters, diaries, and more. Baker also conducted dozens of interviews—three of his subjects were more than one hundred years old—and discovered caches of historic photographs and paintings.

A groundbreaking work of history and a deeply personal journey of discovery, The Washingtons of Wessyngton Plantation is an uplifting story of survival and family that gives fresh insight into the institution of slavery and its ongoing legacy today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Washingtons of Wessyngton Plantation by John Baker,John F. Baker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

The Photo in My Textbook

As a young child in the 1960s, my maternal grandfather took me for a ride in the country nearly every Sunday afternoon after church. We would drive about ten miles northwest of Springfield, Tennessee, and would pass by an impressive mansion, which sat some distance off the road. My grandfather would say, “That’s Washington, where your people came from on your grandmother’s side.”

I discovered the story of my ancestors by accident while flipping through the pages of my seventh-grade social studies book, Your Tennessee. At the beginning of the chapter “Black Tennesseans,” I spotted a photograph of four African Americans. In the 1970s little was taught in public schools about black history other than the Civil War period, so the picture really intrigued me. I kept being drawn to this photograph and examined it carefully. The people were dressed well and looked dignified. I knew from their clothing that the photo was nearly one hundred years old. Each time I went to class, I would turn to the photo because the couple seated reminded me of some of my family members—the woman and my maternal grandmother especially.

My grandmother Sallie Washington Nicholson moved to Indianapolis in 1941 and from there to Chicago. Each year she would come home to visit. On her visit, in 1976, when I was thirteen years old, she spent the weekend with her brother and sister-in-law Bob and Maggie Washington in Cedar Hill. She called my mother and told her to have me bring a camera when we came to pick her up because she had something she wanted me to photograph. When my mother and I arrived, my grandmother showed us an article from the Robertson County Times, published in Springfield. I immediately realized that this was the same photograph I had seen in my school textbook. The caption under the photograph listed the names of the former slaves, the owner, and the name of the plantation: Wessyngton. The caption read: “Another of the pictures from Wessyngton. Seated left: Emanuel Washington, Uncle Man the cook, seated right: Hettie Washington, Aunt Henny the head laundress (Uncle Man’s wife), standing left: Allen Washington, the head dairyman, standing right: Granville Washington (George A. Washington’s valet or body servant). Taken at Wessyngton [1891].”

I remember to this day what happened next:

“Who are these people, Big Mama?” I asked.

“That’s my grandfather and grandmother,” she said, pointing to the seated couple. “My grandfather was the cook at Washington.” I knew that she was really talking about Wessyngton because most black people in the area refer to the plantation as Washington. “And that is where we got the Washington name.”

Although I had seen the photograph in the textbook many times, it assumed a different meaning once I knew that those people were my ancestors. I was in shock. I could hardly wait to get back to school and tell my classmates that my ancestors were in our history book. I looked at each person in the photograph carefully. I looked at Emanuel, Henny, Allen, and then Granville. Pointing to Granville, I asked, “Who is this white man? Was he the slave owner?” My grandmother and uncle replied at the same time, “He’s not white, he is related to us too! Granville was our cousin. Papa used to talk about him all the time. He said George Washington who owned the Washington farm was his father by a slave girl. Granville’s mother was kin to Papa on his mother’s side of the family.”

Sallie Washington Nicholson, My Grandmother, 1909–1995

I was the youngest child in the family. My mother died having twins when I was three. My parents were Amos and Callie White Washington. My father was born at Washington in 1870, his parents were Emanuel and Henny Washington, who were born slaves on the Washington plantation. My grandfather died before I was born, and our grandmother died when I was too little to remember her, but Papa used to talk about them and our other relatives all the time. His daddy was the cook at Washington [Wessyngton] and when Papa was just a small boy he used to follow his daddy around the Big House and played in the kitchen at Washington while his daddy worked. Papa could make cornbread that was as good as cake. I guess he learned that from his daddy. Papa said he was taught to read and write by some of the Washington children he played with as a child.

Sallie Washington Nicholson (1909–1995).

Did they ever say how the slaves were treated at Washington?

Papa said they always treated his daddy like he was part of the family because he was the cook and used to tell all the children ghost stories. Papa said his daddy was the best cook there was. I don’t know if they treated them all like they did him or not. They say the Washingtons never caused the breakup of families by selling slaves from the plantation. Our grandmother Henny was part Indian and so was our mother’s father, Bob White. After our grandfather got too old to cook and went blind, John Phillips cooked at Washington. He married our cousin Annie Washington who was Cousin Gabe Washington’s daughter. I think Cousin Gabe was the last of the slaves that stayed there after they were freed. I used to talk to him all the time when we went down there. The Washingtons were really fond of him too. When we were children just about all older people were called “uncle” or “auntie” whether they were related or not. This made it that much harder to tell how everybody was kin. We even had to address our older sisters and brothers with a title. You could not just call them by their first names. That is why I say Sister Cora.

I always wondered why you called Aunt Cora “Sister Cora” and she didn’t say “sister” when she was talking to you.

That’s because she was the oldest. I called my brother Baxter and sister Henrietta by their names because they were closer to my age.

A lot of our cousins lived down at Washington when we were growing up. Allen Washington that’s on the picture with our grandparents was Guss Washington’s grandfather. Guss married our cousin Carrie, and both of them worked down at Washington for years and years. You can probably talk to Carrie, because she can remember lots of things and so will Sister Cora.

When we were children Papa used to make sure we went to church. We went to the Antioch Baptist Church in Turnersville. Papa always sent us, but he never went there, he always said he belonged to a white Catholic church [possibly St. Michael’s]. He later joined South Baptist Church in Springfield and was baptized when he was in his eighties. When I was a child Papa always told us to pray at night as if it was our last time to make sure we went to Heaven, and never go to bed angry with anyone without making things right. He said that’s how his parents taught him to pray.

I went to school in Sandy Springs at Scott’s School and some at Antioch School. Our cousin Clarine Darden was my first teacher. My mother died when I was small, so they started me to school early. I can’t even remember what Mama looked like. When I first married your grandfather, I woke up in the middle of the night and looked toward the foot of my bed and there Mama stood. I was afraid and hid my head under the covers. I looked out a second time and she was still there. I could not wake your grandfather, so I was afraid to look out again. After I described her to my brother and sister they said it was our mother.

After Mama died, my father married Jenny Scott, she was the daughter of Mr. Joe Scott and Mrs. Fannie Scott, who lived down by Scott’s Cemetery. Mr. Joe Scott was a Washington slave too.

My mama’s mother lived near us. Her name was Fannie Connell White Long. She was a midwife who delivered black and white babies. We called her Granny Fanny. She died in 1920 during the flu epidemic. A whole lot of people died with the flu back then and tuberculosis. My sister Henrietta died from tuberculosis one month before your mother was born in 1928. Henrietta always looked after me after Mama died, and so did Bob. Some of our family was buried in White’s Cemetery, which was owned by our family. My great-grandfather Henry White bought that property right after he was freed.

On the fourth Sunday in May they hold Antioch Baptist Church’s homecoming. There would be people from everywhere. I used to go often to get to see our relatives and friends who had moved up North.

They used to have a hayride in town in Springfield that used to go down to Washington when I was young. When I was carrying your mother, we went down there and a boy fell off the wagon, Curtis “Six Deuce” Meneese, and had to have his leg amputated. I never went on the ride after that. Several of our cousins still lived at Washington then.

Our family came here with the first Washington that started the plantation. I don’t know what year it was, but I think our family was there the whole time or close to the start of it. Most of our family stayed there after they were set free.

Bob Washington, My Great-uncle, 1897–1977

I remember my granddaddy and grandmamma. Everybody called my granddaddy ‘Uncle Man,’ but his name was Emanuel. Our grandmother was named Henny. Our sister Henrietta was named after her. Our mother died having twins in 1913, and Grandpa Man’s sister, Aunt Sue, stayed with us to help Papa out with the children. I remember her burning the toast when she cooked and wanted us to eat it anyway. She was born a slave down at Washington and was older than our grandfather. She was probably close to one hundred when she died. Grandpa Man had another sister, Clara Washington; she died in 1925 and was nearly one hundred when she died; she was Jenny Hayes’s mother. Most of our people have lived to get pretty old. Papa had a brother named Grundy Washington who lived in Clarksville, Tennessee. He had ten or twelve children too. We have relatives everywhere. Many of them moved up North. Our oldest brother, Willie, moved up North, then our brother Baxter and your grandmother later moved up there. Some of them tried to get me to move, but I never did.

Our father said our family came from Virginia with the Washingtons. They were some kin to the president, and that’s where we got our family name. Some of the family still lives down in the old Washington house. If you call down there and tell them who you are, they may be able to help you find something. They still have some of the old slave houses and everything else down there. [My great-uncle told me the plantation was not far from his house. My great-aunt Maggie confirmed what my grandmother and great-uncle said about the family. Her maternal ancestors also came from the Wessyngton Plantation.]

Bob Washington (1897–1977) and Maggie Polk Washington (1904–2003), on their fiftieth anniversary.

I questioned them all I could about the people in the photograph that night. My mother finally interrupted and told them I would keep asking questions as long as they would answer them and that I should be a lawyer. This ended my first of many interviews. I had heard bits and pieces about our family growing up as I always hung around older relatives. I suppose the old adage that a picture is worth a thousand words is really true. Now I was determined to get every shred of information I could to find out more about our distant past.

CHAPTER 2

That’s Washington, Where Your People Came From

After the discovery of my ancestors in the photograph, I was so excited I could hardly sleep. The next morning I looked in the phone book and called out to Wessyngton. Anne Talbott, a descendant of the plantation’s original owner, answered the phone. I introduced myself and told her that I had seen the article in our local newspaper and that I was the great-great-grandson of Emanuel and Henny Washington who were born at Wessyngton. Anne told me that Emanuel’s family had remained on the plantation after they were freed, and they had many records of the slaves’ births, photographs, and, she said, a portrait of my great-great-grandfather was still hanging in the mansion. She told me that she operated a bookstore in Springfield and she would gladly meet me there and show me some of the records and photographs.

When I arrived at the bookstore, Anne greeted me and showed me an old photo album with several pictures of my great-great-grandparents and a beautiful portrait of my great-great-grandfather painted by a famous artist, [Maria] Howard Weeden. I was amazed. Then she showed me copies of a list of about eight legal-sized pages of names. These were the names of slaves who had been born on the Wessyngton Plantation from 1795 through 1860. On the second page of the document I found “Manuel born April 23rd 1824”—my great-great-grandfather! I continued searching and found “Henny was borne May 26, 1839”—my great-great-grandmother! It was exciting to see my family history unfold before my eyes. Anne asked if I saw any other names I was familiar with. There were more than two hundred names on the document. Since the names of the slaves were recorded by several Washington family members during a sixty-five-year span, their spellings varied. Anne then looked further and found “General born December 25, 1854 Hena’s child,” then “born November 23rd 1856, Grunday, Henna’s child,” then “1859 born January 22nd Henna’s child Cornelia.” She said, “These should be your great-great-grandparents’ children—have you ever heard of them?” I had never heard of General or Cornelia, but I remember many times hearing that my g...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Prologue

- Chapter 1: The Photo in My Textbook

- Chapter 7: Working from Can't to Can't

- Chapter 13: August the 8th

- Epilogue: To Honor Our Ancestors

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography of Primary Sources

- Selected Bibliography

- Illustration Credits

- Copyright