- 688 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

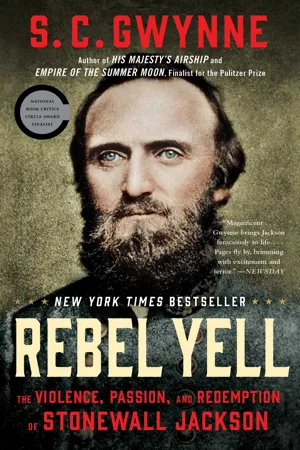

Finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, the epic New York Times bestselling account of how Civil War general Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson became a great and tragic national hero.

Stonewall Jackson has long been a figure of legend and romance. As much as any person in the Confederate pantheon—even Robert E. Lee—he embodies the romantic Southern notion of the virtuous lost cause. Jackson is also considered, without argument, one of our country’s greatest military figures. In April 1862, however, he was merely another Confederate general in an army fighting what seemed to be a losing cause. But by June he had engineered perhaps the greatest military campaign in American history and was one of the most famous men in the Western world. Jackson’s strategic innovations shattered the conventional wisdom of how war was waged; he was so far ahead of his time that his techniques would be studied generations into the future.

In his “magnificent Rebel Yell…S.C. Gwynne brings Jackson ferociously to life” (New York Newsday) in a swiftly vivid narrative that is rich with battle lore, biographical detail, and intense conflict among historical figures. Gwynne delves deep into Jackson’s private life and traces Jackson’s brilliant twenty-four-month career in the Civil War, the period that encompasses his rise from obscurity to fame and legend; his stunning effect on the course of the war itself; and his tragic death, which caused both North and South to grieve the loss of a remarkable American hero.

Stonewall Jackson has long been a figure of legend and romance. As much as any person in the Confederate pantheon—even Robert E. Lee—he embodies the romantic Southern notion of the virtuous lost cause. Jackson is also considered, without argument, one of our country’s greatest military figures. In April 1862, however, he was merely another Confederate general in an army fighting what seemed to be a losing cause. But by June he had engineered perhaps the greatest military campaign in American history and was one of the most famous men in the Western world. Jackson’s strategic innovations shattered the conventional wisdom of how war was waged; he was so far ahead of his time that his techniques would be studied generations into the future.

In his “magnificent Rebel Yell…S.C. Gwynne brings Jackson ferociously to life” (New York Newsday) in a swiftly vivid narrative that is rich with battle lore, biographical detail, and intense conflict among historical figures. Gwynne delves deep into Jackson’s private life and traces Jackson’s brilliant twenty-four-month career in the Civil War, the period that encompasses his rise from obscurity to fame and legend; his stunning effect on the course of the war itself; and his tragic death, which caused both North and South to grieve the loss of a remarkable American hero.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE

THE UNIMAGINED WAR

CHAPTER ONE

AWAY TO RICHMOND

For Thomas J. Jackson the war started precisely at 12:30 p.m. on the afternoon of April 21, 1861, in the small Shenandoah Valley town of Lexington, Virginia. As beginnings go, it was grand, even glorious. Fort Sumter had fallen to the rebels on April 13. Virginia had seceded on the seventeenth, and since then its citizens had been in the grip of a sort of collective delirium that had sent them thronging into the streets. It was that way everywhere in the country, North and South. Though no one could say what was going to happen next, or where it might happen, and very few knew what it might be like to actually shoot another human being, Americans everywhere felt a new and joyous sense of clarity and purpose. War would be the way forward, not the old-fashioned idea of war as horror and heartbreak but a new and heady notion of grand adventure and impending glory. And so Lexington, a quiet, picturesque college town of 2,135 on a hilltop at the southern end of the valley, was being turned into an armed camp, in the happiest possible sense of that term.1 Volunteer companies were organized in the streets; militiamen marched to and fro; students from Washington College drilled under their Greek teacher; ladies sewed regimental flags and mended socks; lunches were packed; old squirrel guns and fowling pieces and muskets from the War of 1812 were dragged out of storage, cleaned, and oiled. There was an atmosphere of picnic and parade. As one Confederate soldier recalled, those days were “the only time we can remember when citizens walked along the lines offering their pocketbooks to men whom they did not know; that fair women bestowed their floral offerings and kisses ungrudgingly and with equal favor among all classes of friends and suitors; when the distinctions of wealth and station were forgotten, and each departing soldier was equally honored as the hero.”2

Meanwhile, across town at the Virginia Military Institute, the South’s oldest military college, the cadets were embarking on a solemn mission. Three days before, their superintendent had received orders from the governor to send them immediately to Richmond to help drill the raw recruits who were arriving in large numbers. Now, in the warm sunshine of the Sabbath morning of April 21, on a promontory high above the North Branch of the James River and with the mountains rising in the distance, they were preparing to do just that. Around noon, 176 of them were in line in front of their castellated barracks, young, fresh-faced, and deliberately serious, with “their cheeks aglow, and their eyes sparkling with the expectation of the military glory awaiting them,” as one observer recalled.3 They wore short-billed kepis and shell jackets with brass buttons. They stood at attention: four small companies in eight immaculate lines. Flanking them was their baggage train, wagons loaded with equipment, and drivers, mounted, whips in hand, waiting for the command to move out.4 It was a grand and inspiring scene—for little Lexington, anyway—and a crowd of people had gathered on Institute Hill to watch it.

In front of the cadets stood their commander, the unimposing Major Thomas J. Jackson. He was thirty-seven years old, trim, bearded, a bit gaunt, and a shade under six feet tall. You would have noticed his pale, blue-gray eyes; his high, wide forehead; and his thin, bloodless lips, which always seemed tightly pressed together. For the occasion he had worn his very best uniform: a faded, dark-blue, double-breasted coat with a major’s epaulets, blue trousers with gold piping, a sword, sash, and forage cap.

It is worth taking inventory of him at the moment he rode off to war. Though he held himself ramrod straight on the parade ground, his bearing seemed odd, even to a casual observer: more awkward than military, more graceless than dignified. He had large hands and feet, and seemed not to know quite what to do with them. And this strangely stiff posture suggested exactly how these cadets saw him: as a perfect martinet, a humorless, puritanical, gimlet-eyed stickler for detail, a strict enforcer of every rule and regulation. He was such a literalist when it came to duty that he had once, while in the army, worn heavy winter underwear into summer because he had received no specific order to change it. Once, when seated on a camp stool with his saber across his knees, he was told by VMI’s superintendent to “remain as you are until further orders.” The next morning the superintendent found him seated on the camp stool in the same position, because, according to Jackson, “you ordered me to remain here.”5 He insisted that his students obey his orders just as unquestioningly. He was as painfully formal in conversation as he was in class.

Worse still, from the students’ point of view, he not only taught the school’s toughest and most loathed course, “Natural and Experimental Philosophy”—essentially what we call physics, though it included math and such other disciplines as optics and astronomy—he was also, by universal acclaim, VMI’s worst teacher. Though he was presumed to understand the dreaded Bartlett’s Optics textbook that he taught, he was unable to impart that wisdom to his students. He insisted on rote recitation; he explained little or nothing. He had survived an attempt led by the school’s alumni six years before to get rid of him, for all of those reasons.6 Jackson also taught artillery drill, at which he seemed only marginally more competent than he was as a science teacher.

He seemed in other ways to be a man who had at least found his place in the world. He had been born in modest circumstances in Clarksburg, in northwestern Virginia (now West Virginia), orphaned at seven, and raised mainly by his uncle, who owned a gristmill and farm. In spite of a poor childhood education, he had somehow made it through West Point. Though he was childless, he was said to be happily married. He was known to everyone as a devout Christian. He was a deacon in the Presbyterian Church, to which he devoted a good deal of his time. He had a very decent brick house in town, and a small farm in the country, and owned six slaves.

Those who knew him well could also have told you that he was a victim of a host of physical ailments, real and imagined, and that he traveled long distances in search of water cures that involved both drinking and soaking in supposedly healing waters. That his diet was odd, too, often consisting of water and stale bread or buttermilk and stale bread and he was so resolute about this that he carried his own stale bread with him when invited out to dinner. As he stood by the barracks inspecting his troops that day, he might have been charitably described as a comfortable mediocrity: a decent enough man, a harmless eccentric, an upstanding Christian and good citizen who, unfortunately, was an inept teacher. It is worth noting that the preceding description is far from complete. There was a good deal more to him even then than most of his students or colleagues ever suspected—more, indeed, of what made him great later on. He held his secrets close. He was never what he seemed to be, not in Lexington, not later in the war.

There was, however, one item that stood out on Major Jackson’s curriculum vitae as of that bright April afternoon. That was his conspicuous and, to many, uncharacteristic record in the Mexican-American War in 1847. Though he seemed to most of his acquaintances in Lexington to have the personality of neither warrior nor leader, it was said that he had exhibited great bravery in battle and that the commanding general Winfield Scott himself had singled out the young Jackson for praise. Students and faculty at VMI had heard the story, though it made no particular sense to them. Jackson seemed the furthest thing from a hero. Whether this brief, anomalous glory held any meaning in the year 1861, no one could yet say.

A little after noon, Jackson removed his cap and called out loudly, “Let us pray.” The pastor of the local Presbyterian church, the Reverend Dr. William S. White, piped up with a short prayer, followed by a collective “Amen.” It was time to go. Or it would have been if someone other than Jackson had been commanding. Though the battalion was ready to move out—in fact, the cadets were dying with joy and anticipation—Jackson insisted that it depart precisely at 12:30, as planned. Jackson was a fanatic about duty, and duty dictated punctuality, and he was not, merely for the sake of this romantic war that everyone seemed to want, going to waive his rules. When his second in command, Raleigh Colston, a teacher of foreign languages, approached him and said, “Everything is ready, sir. Shall I give the command forward?,” Jackson’s answer was a clipped “No.” They would wait. Jackson sat on a camp stool, unmoving, while the minutes ticked by.7

Finally, as the college bells rang 12:30, Jackson mounted his horse, wheeled toward the cadets, then shouted, “Right face! By file left, march!”8 As the young men marched, Jackson remained motionless and expressionless. One cadet later recalled “how stiffly he sat on his horse as the column moved past him.”9 Thus they went off to war, to the sound of fife and drum, Jackson somewhat awkwardly shepherding the small column that contained the sons of some of the South’s most prominent families. A mile away, across the small bridge that spanned the river, lay the carriages, wagons, and stagecoaches that would take them to the town of Staunton, where they would board a train for Richmond. The moment was sweetly sad, as were moments like this that were taking place across the country. It would have been sadder still if the assembled onlookers had known that Jackson and many of his ruddy-cheeked charges would never see Lexington again.

• • •

Behind the pomp and circumstance lay the curious fact that the stern, inelegant man leading the column had done everything in his power to prevent the war that he was now marching off to fight. He hated the very idea of it. His conviction was in part due to his peculiar ability, shared by few people who landed in power on either side—Union generals Winfield Scott and William Tecumseh Sherman come prominently to mind—to grasp early on just how terrible the suffering caused by the war would be, and just how long it was likely to last.10 The detail-obsessed physics professor’s embrace of such a large abstraction is perhaps an appropriate introduction to the man himself: Jackson’s brilliance was that he understood war. He understood it at some primary, visceral level that escaped almost everyone else. He understood it even before it happened.

In the months leading up to the war Jackson had remained a confirmed Unionist. He opposed secession. Though he was a slave owner, he held no strident, proslavery views. Indeed, his wife, Anna, wrote that she was “very confident that he would never have fought for the sole object of perpetuating slavery.”11 He had attended West Point, had been in combat under the flag of the United States of America, and had later served in the country’s peacetime army. He was a patriot, in the larger sense of the word. As a Christian he was shocked by what he saw as the ungodly and inappropriate enthusiasm on both sides to settle their differences by fighting. “People who are anxious to bring on war don’t know what they are bargaining for,” he wrote to his nephew.12

In February 1861, the failure of a Virginia-sponsored peace conference in Washington made Jackson so fearful of war that he called upon his pastor, the Reverend White, to talk about what might happen. “It is painful to discover with what unconcern they speak of war, and threaten it,” Jackson told him. “They do not know its horrors. I have seen enough of it to make me look upon it as the sum of all evils.”13 His wife, Anna, offered a striking summary of his beliefs in those early days. “I have never heard any man express such an utter abhorrence of war,” she wrote. “I shall never forget how he once exclaimed to me, with all the intensity of his nature, ‘Oh, how I deprecate war!’ ”14 But there was more to it than that. According to his sister-in-law, Maggie Preston, who was perhaps his closest friend, Jackson also recoiled physically at war’s violence. “His revulsions at scenes of horror, or even descriptions of them,” she wrote, “was almost inconsistent in one who had lived the life of a soldier. He has told me that his first sight of a mangled and swollen corpse on a Mexican battlefield . . . filled him with as much sickening dismay as if he had been a woman.”15

And now he was prepared to do what he could to stop the imminent horror. His chosen form of activism was characteristic of the man: prayer. He would pray. He would petition God, and God would stop the madness. When he had thought about it some more it occurred to him that he could do even more than that. So he went to the Reverend White with a proposal. “Do you not think that all the Christian people of the land,” he asked White, “could be induced to unite in a concert of prayer to avert so great an evil? It seems to me that if they would thus unite in prayer, war might be prevented and peace preserved.” Jackson believed in the power of prayer; now he was proposing to harness the entire nation to that power, a gigantic, country-sweeping petition sent up to God: a national day of prayer to overturn the political idiocies of the past half century. White encouraged him, and Jackson did what he could to make it happen. Since none of his correspondence on the subject has survived, we don’t know how far he got with the plan. We do know that other Christians in other churches, perhaps sharing his sense of desperation, had proposed the same thing. He pursued it as best he could, writing letters to clergymen in the North and South. His name eventually appeared on several communications from Northern churches supporting the day of prayer.16 The event never came to pass. Jackson prayed ardently over it anyway. When he was called on in church to lead prayers, the wish he invariably expressed was “that God would preserve the whole land from the evils of war.”17

That did not mean he was not fully prepared to do his duty when the orders came down from Richmond. His main regret, it seemed, was that he was losing his precious Sabbath, the day appointed for the march. On the eve of his departure, he had told Anna that he hoped that “the call to Richmond would not come before Monday,” which would allow him to spend the Sabbath quietly and “without any mention of politics, or the impending troubles of the country.”18 When those orders came anyway, Jackson knelt somberly with her in their bedchamber on Sunday morning. In a quavering voice he read from Corinthians and committed them both to the protection of God. “His voice was so choked with emotion that he could scarce utter the words,” wrote Anna. “One of his most earnest petitions was that, ‘if consistent with His will, God would still avert the threatening danger and grant us peace.’ ” Jackson still hadn’t given up. He was ready to die for Virginia and for the South, but he still did not believe God was going to let this happen.

If Jackson could seem at times like a Quaker pacifist in a country that was lunging eagerly toward war, there was also a hint, in a letter written in January 1861 to his nephew Thomas Jackson Arnold, of a darker, more complex view. In it he repeated his desire to avert war, but added a qualifier that Arnold found so disturbing that he later edited it out of his own reverent biography of Jackson. “I am in favor of making a thorough trial for peace,” wrote Jackson, “and if we fail in this and the state is invaded to defend it with terrific resistance—even to taking no prisoners.”19 Taking no prisoners. That idea was well outside the mainstream of American political and military thought at the time; no one in a position of power on either side was seriously considering a “black flag” war in the spring of 1861. Jackson went on to say that if “the free states . . . should endeavor to subjugate us, and thus excite our slaves to servile insurrection in which our Families will be murdered without quarter or mercy, it becomes us to wage a war as will bring hostilities to a speedy close.”20 By that he meant making war so brutally expensive for both sides that they would quickly sue for peace. He meant instant, total war. Amid Jackson’s ardent peace prayers, these harder-edged, less charitable thoughts dwelt also.

CHAPTER TWO

THE IMPERFECT LOGIC OF WAR

Thus the contented, domestic man who d...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Epigraph

- Map of Jackson’s Theater of Operations: April 21, 1861–May 10, 1863

- Prologue: Legends of Spring

- Part One: The Unimagined War

- Part Two: The Man Within the Man

- Part Three: Valley of the Shadow of Death

- Part Four: Stirrings of a Legend

- Part Five: All That Is Ever Given to a Man

- Photographs

- Acknowledgments

- About S. C. Gwynne

- Appendix: Other Lives, Other Destinies

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Photograph Credits

- Index

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Rebel Yell by S. C. Gwynne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.