![]()

1

THE AMBIGUOUS HERO

Ronald Reagan as Conservatism’s Model and Problem

“You can choose your Reagan.”

“I was 13 years old. . . . There was one afternoon my father called me into the room and he said, ‘Listen, you’ve got to watch this. You’ve got to see what this man is saying.’ And there in the TV was this former actor from California. And he looks right at me. He looked right at my father. But he was really speaking to an entire nation. And he said things to us that intuitively made sense. He talked about liberty and freedom. He talked about balanced budgets. He talked about traditional values and personal responsibility. And my father looked at me and said, ‘Well, son, we must be Republicans.’ And, indeed, we were, and are. That’s the party I joined.”

On a late June night in Mississippi in 2014, Chris McDaniel offered this warm invocation of the Gipper to open what most thought would be a concession speech. McDaniel had just lost a bitterly contested Republican runoff to incumbent senator Thad Cochran. The result came as a shock to McDaniel and his supporters. Just three weeks earlier, he had run first in the primary, only narrowly missing the majority he needed to avoid a second round. Incumbents forced into runoffs usually lose in Mississippi. Cochran won anyway.

As it happened, it was not a concession speech at all. McDaniel pledged to fight on and contest the outcome—in Reagan’s name, of course—though his efforts ultimately failed. The decisive votes against McDaniel in the second round came from African-American Democrats who had crossed into the Republican contest (as they were allowed to under state law) to defend their state’s seventy-six-year-old incumbent. “There is something a bit strange, there is something a bit unusual about a Republican primary that’s decided by liberal Democrats,” McDaniel insisted. “This is not the party of Reagan.”

McDaniel had a point. The coalition Cochran put together and the way he did it was anything but orthodox by most conservative standards. McDaniel, a Tea Partier who embodied a kind of libertarian marriage with neo-Confederates, had a fair claim to being the new model of the old Reagan alliance. McDaniel’s antigovernment fervor extended to refusing to say whether he would have voted for emergency assistance for his own state after Hurricane Katrina. “That’s not an easy vote to cast,” he had explained in an interview that came back to haunt him. The summer before, he had delivered the keynote address at an event sponsored by a chapter of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, a group that continues to think the wrong side won the Civil War. “The preservation of liberty and freedom was the motivating factor in the South’s decision to fight the Second American Revolution,” the group declares on its website. “The tenacity with which Confederate soldiers fought underscored their belief in the rights guaranteed by the Constitution.” McDaniel added a strong dose of evangelical Christianity to his appeal. “There is nothing strange at all about standing as people of faith for a country that we built, that we believe in,” he had declared in his nonconcession.

By virtually all reasonable standards, Cochran was a staunch Mississippi conservative. But he was also a proud appropriator who worked amicably with Democrats to pass budgets that included plenty of money for projects of local interest that knew no party affiliation. This was his sin, not only in McDaniel’s eyes but also in the view of Washington-based antispending groups such as the Club for Growth and FreedomWorks. Both backed McDaniel.

Cochran’s campaign, of necessity, turned into a textbook lesson in the contradictions of antispending conservatism. If the ideologues and some of the Washington-based groups disliked Cochran for his relaxed attitude toward the flow of Beltway dollars, many Mississippi Republicans, especially business groups and the politicians who ran local governments, were grateful for his genial approach to federal largesse, particularly in securing the billions that helped rebuild the Gulf Coast communities after Katrina.

“By God’s grace, he was chairman of appropriations for two years during Katrina, and it made all the difference in the world,” former governor Haley Barbour told me a couple of weeks before the primary. With Cochran slated to head up the Senate Appropriations Committee again if the Republicans took back the Senate, the state’s establishment desperately did not want him to retire. “A whole lot of different people said, ‘Thad, don’t put yourself first. Put Mississippi first. You owe it to us to run again,’ ” Barbour recounted. When Cochran finally assented, the Barbour organization went to work.

Pause for a moment to consider that a state known for its deep antipathy to Washington—for having, as the Confederate veterans group would insist, a very particular view of “the rights guaranteed by the Constitution” to the states—just happens to get $3.07 back from the federal government for every dollar it sends in. It ranks number one among the states in federal aid as a percentage of state revenue. Big government in Washington might still have been the enemy in Mississippi, but its dollars were as welcome there as in any of the country’s most liberal precincts.

The 2014 Republican Senate primary in Mississippi provided a particularly pointed lesson in the tensions and contradictions within contemporary conservatism. Federal spending is an evil, except when the money comes into your own state. African-Americans will be left to the other side, except when a conservative politician needs them. Since the GOP primary electorates are often too conservative to nominate a candidate with wide appeal beyond the Republican base, temporarily borrowing the other side’s base is permissible in emergencies. And if you are a Republican, you can declare that whatever you are doing would have been blessed by Ronald Reagan.

Cochran’s victory was an ironic tribute to the fiftieth anniversary of Freedom Summer and its drive to secure black voting rights. A Republican establishment initially built on white backlash against civil rights won an internal party contest only with the help of voters whose access to the ballot had been secured by the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, a law that so many whites in Mississippi and in other states of the Deep South had so militantly resisted. Between the primary and the runoff, the New York Times concluded, “the increase in turnout was largest in heavily black counties, particularly in the Mississippi Delta.” In Jefferson County, where African-Americans represent 85 percent of the population, turnout jumped by 92 percent—the largest increase in the state.

This is what infuriated McDaniel. “Today the conservative movement took a backseat to liberal Democrats in the state of Mississippi,” he told his supporters. “In the most conservative state in the Republic this happened. If it can happen here, it can happen anywhere. And that’s why we will never stop fighting.”

But in truth, all sides in the Mississippi showdown saw themselves as fighting for Reagan’s legacy. That is how protean it had become. When he had spoken to me before the primary, Barbour had proudly recounted his work as a political aide in Ronald Reagan’s White House and insisted on the great philosophical continuity from Reagan to present-day conservatism. Now, as then, conservatives were still committed to “limited government, lower taxes, less spending, balanced budgets, rational regulation, peace through strength, open markets and free trade, tough on crime, strengthen families, welfare reform—that kind of stuff.”

“That’s the same stuff Reagan was for,” Barbour said.

But McDaniel would have stoutly disagreed with something else Barbour told me that day. “In the two-party system,” he observed, “purity is the enemy of victory.” And there is the rub. Reagan can be seen as the champion of purity, and also as its enemy.

That both Chris McDaniel and Haley Barbour could reasonably claim to be following in Reagan’s footsteps speaks to the ambiguous character of the Reagan legacy. There is the Reagan who excited the conservative movement before he became president and the chief executive who could govern in a pragmatic way and accept the limits imposed on him throughout his presidency by a House of Representatives led by Democrats. He campaigned thematically and governed realistically. The Reagan who made his name as Barry Goldwater’s most effective advocate in 1964 was different from the Reagan who was governor of California or president of the United States.

When I explored this dilemma one day with Charles Krauthammer, the conservative columnist and Fox News commentator, he cut to the chase. “You can choose your Reagan,” he said. Conservatives do it all the time.

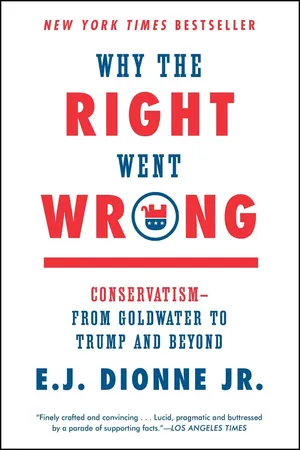

Unraveling the riddles of the American right involves dissecting the twin and overlapping legacies of Reagan and Goldwater. I begin with the Reagan Condundrum because he remains the dominant figure of the conservative imagination and was a touchstone for Republican candidates during the 2016 campaign. Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker said he celebrated Reagan’s birthday every year with “patriotic songs” and “his favorite foods—macaroni and cheese casserole and red, white and blue jelly beans.” Senator Ted Cruz commissioned an oil painting of Reagan at the Brandenberg Gate in Berlin, and it hangs in his Senate office. There was no higher compliment to a candidate than to compare him to Reagan. Thus did conservative writer Paul Kegnor offer an extended essay in the American Spectator praising a May 2015 foreign policy speech by Senator Marco Rubio by arguing that he was “starting to sound like Reagan’s heir.”

Yet it has also become a habit of liberals, especially since the rise of the Tea Party, to say that the Reagan who served as president of the United States would have no chance of winning a Republican nomination and to cite his many apostasies. Jon Perr, a writer for the left-of-center Daily Kos blog, offered an impressive list. Reagan, he pointed out, raised taxes on a number of occasions (after first cutting them). He expanded the size of government. He strongly supported the redistributionist Earned Income Tax Credit. He offered amnesty to undocumented immigrants. He sought to eliminate nuclear weapons. And he approved some protectionist measures on trade.

This line of argument understandably irritates Reagan conservatives. “Those who write that Reagan would not now fit in the party he largely created make the mistake so many do in discussing Reagan,” wrote his biographer and admirer Craig Shirley. “They confuse tactics with principles.” And, yes, Reagan was also responsible for a steep cut in the top income tax rate—from 70 percent when he took office to 28 percent when he left. He broke the air traffic controllers union, helping set off a long decline in the private sector labor movement. He presided over a major military buildup.

Particularly in his first year in office, he aroused rage among liberals for steep cuts in domestic programs. One episode might serve as a reminder of how progressives felt about Reagan when he was in office: a 1981 Department of Agriculture regulation that declared ketchup a vegetable under the school lunch program. Liberals denounced this absurdity as representative of Reagan’s overall approach to programs for the poor. The Gipper, ever the Haley Barbour–style pragmatist, eventually responded to the mockery by withdrawing the rule.

National security conservatives might concede merit to the pragmatic reading of Reagan’s domestic record but insist that he was a rock when it came to standing up to the Soviet Union (“Tear down this wall!”). He went to great lengths to restore American military strength. His anticommunist credentials are certainly unassailable and the military spending he supported—totaling $2.8 trillion—is a simple fact. He did, indeed, initiate the Strategic Defense Initiative, popularly known as “Star Wars.” And his success in persuading Western European nations to accept Pershing missiles in the early 1980s sent an important signal to the Soviet Union that its efforts to divide the Western alliance would fail. It may well have been the key step in the ultimate unraveling of the Soviet Union.

But viewing Reagan as a military interventionist misreads his record. In a deeply misguided decision, he sent American marines to Beirut, but then promptly withdrew them after 241 in their ranks were killed in a terrorist attack. The record suggests that he learned from this tragedy. He may have armed the Contras, who were fighting to undermine the leftist Sandinista regime in Nicaragua, but he resisted calls from Norman Podhoretz, William F. Buckley Jr., and other Cold Warriors to send troops to Central America. “Those sons of bitches won’t be happy until we have 25,000 troops in Managua,” Reagan complained to his chief of staff, Ken Duberstein. His more hawkish supporters were disappointed. Podhoretz, a founding neoconservative, grumbled that “in the use of military power, Mr. Reagan was much more restrained” than his loyalists had hoped. Reagan’s intervention in Grenada was, to put it gently, a minor engagement—the American military against an army of six hundred. Still, as the writer Peter Beinart noted, Grenada gave him a military victory to brag about, at a very low cost. “Reagan’s political genius,” Beinart said, “lay in recognizing that what Americans wanted was a president who exorcised the ghost of Vietnam without fighting another Vietnam.”

And when Reagan proved to be eager to achieve arms reduction with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, many conservatives were enraged. George F. Will, the conservative columnist and one of Reagan’s most loyal defenders, grumbled that Reagan was “elevating wishful thinking to the status of political philosophy.” In the negotiations, Will mourned, the administration had crumpled “like a punctured balloon.”

Conservatives will almost always say it was Reagan’s arms buildup that effectively bankrupted the Soviet Union and sped its collapse. But a strong case can be made that by dealing so openly and hopefully with Gorbachev, Reagan undercut Kremlin hard-liners and strengthened the forces of glasnost and perestroika. It can be argued, in other words, that the Soviet Union was brought down as much by Reagan the Peacemaker as by Reagan the Warrior.

The ambiguities in Reagan’s record are not merely a matter of historical interest. They are vital to today’s debates on the right. These “What Would Reagan Do?” moments occur again and again, but they are especially revealing when it comes to foreign policy, where his legacy is most secure. Consider the all-out brawl in the summer of 2014 between Governor Rick Perry and Senator Rand Paul about the Iraq War and the broader issue of when American troops should be deployed. Their whole exchange revolved around the Gipper.

Writing in the Wall Street Journal, Paul argued that Reagan was widely misunderstood and his legacy had been promiscuously misused. “Though many claim the mantle of Ronald Reagan on foreign policy, too few look at how he really conducted it,” Paul wrote. “The Iraq war is one of the best examples of where we went wrong because we ignored that.”

In defending his own caution about sending American forces abroad, Paul cited the doctrine offered by Reagan’s defense secretary Caspar Weinberger laying down a very stringent set of tests for military intervention: that “vital national interests” of the United States had to be at stake; that the country would go to battle only “with the clear intention of winning”; that our troops would have to have “clearly defined political and military objectives” and the capacity to accomplish them; and that there must be a “reasonable assurance” of the support of U.S. public opinion and Congress. At the core of the Weinberger Doctrine, Paul said, was the principle that war should be fought only “as a last resort.”

The Iraq War, Paul insisted, flunked the Weinberger test. And then he added what turned out to be fighting words: “Like Reagan,” he wrote, “I thought we should never be eager to go to war.”

Perry, then a contender for the party’s 2016 presidential nomination, hit back the next month, charging that Paul had “conveniently omitted Reagan’s long internationalist record of leading the world with moral and strategic clarity.”

“Unlike the noninterventionists of today,” Perry argued on the Washington Post’s op-ed page, “Reagan believed that our security and economic prosperity require persistent engagement and leadership abroad.” Perry told the more familiar story: “Reagan identified Soviet communism as an existential threat to our national security and Western values, and he confronted this threat in every theater,” he wrote. “Today, we count his many actions as critical to the ultimate defeat of the Soviet Union and the freeing of hundreds of millions from tyranny.” And then came the swipe: Reagan had resisted those who “promoted accommodation and timidity in the face of Soviet advancement,” Perry said, adding, “This, sadly, is the same policy of inaction that Paul advocates today.”

Paul did not turn the other cheek. His lengthy counterattack in Politico carried the rather unambiguous headline: “Rick Perry Is Dead Wrong.” Paul accused Perry (who ended his candidacy in September 2015) of offering “a fictionalized account of my foreign policy so mischaracterizing my views that I wonder if he’s even really read any of my policy papers.” And on the crucial Reagan point, Paul’s Gipper was very different from Perry’s Gipper:

Rea...