![]()

1

The Effigy

THE effigy twisted on a thin steel wire.

When Bob Brewer brought his Jeep to a full stop, he could see that the headless figure hung precisely over the spot where he had walked the day before. It was dressed in blue jeans and a sweatshirt. And it was riddled with bullet holes. The dummy’s torso was stuffed with rocks, and it slumped forward in a deadweight slouch—nearly snapping the sapling from which it dangled. There were other ominous changes to the landscape, as well. Tree trunks surrounding the spot had been spray-painted with inverted crosses. A stack of spent rifle shell cases, piled on the boxes that had held them, lay nearby. A trail of yarn, tied to the back of the effigy, led to the pile of used ammunition … in case anyone missed the connection.

Twenty-four hours earlier, on a crisp October morning in 1993, Bob and a friend had arrived at the remote site along a dirt trail in Arkansas’s Ouachita Mountains. They had brought along an old topographical map of the region, a metal detector and a camera for the purpose at hand: to find and record clues leading to what Bob suspected were buried caches of treasure. It was not a farfetched suspicion. The experienced treasure sleuth had previously unearthed caches of Civil War–era gold and silver coins not far from the site, and he had reason to believe that this area was linked to those sites. Over the course of that first day, the two men had discovered and photographed numerous buried clues: rusted plow points and other pieces of metal that served as geographic pointers. The location of the buried directional markers had been carefully recorded on a grid to ensure the correct orientation of each piece, which was then reburied. It was a system that had yielded results in the past and which Bob was steadily improving. As Bob and his friend had headed back to camp that night, he felt sure that he was close to finding something big.

When the men returned the next day with a third treasure-hunting friend, they quickly realized that their plans would have to change.1 They agreed to notify the police about the overnight transformation of their site. When a deputy sheriff and a U.S. deputy marshal for the Forest Service arrived, the officers asked a few questions, took photos of the effigy and removed it—carrying it off as if it were a cadaver.2 As Bob looked on, he wondered about the decision he’d made to pursue a decades-old mystery deep in the Arkansas timberlands.

![]()

2

The Education of a Confederate Code-Breaker

THE backwoods that surround Hatfield, Arkansas, are thick, nearly opaque in places, and vast. Towering pines and hardwoods crowd steep mountain slopes, their canopies eclipsing much of the sun’s rays. On the north-facing ridges, where the giant hardwoods cluster, only the rare splash of sunlight reaches the damp forest soil. This shadowed environment, spiked with its treacherous crags, can seem uninviting—even menacing—for those who come from beyond the rugged hill country of west-central Arkansas. But for those native to the hills, the natural shroud helps keep things private, elemental, protected.

That is why, despite their sometimes unforgiving topography, the Ouachita Mountains have attracted frontier-minded people for millennia. Abundant elk and bison herds lured primitive hunter-gatherers some ten thousand years ago. Prospects of finding gold and silver deposits in Paleozoic-aged veins of quartz charmed Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto into the region in the 1500s, while ample beavers and minks attracted French trappers in the following centuries. The French gave the mountains their name, from the local Quapaw Indian phrase, “Wash-a-taw,” which means “good hunting grounds.” Settlers from Kentucky, Tennessee and surrounding areas began arriving in substantial numbers in the 1830s. Homesteading in a land with limited agrarian potential, these robust Scots-Irish mountaineers carved out a hardscrabble existence.

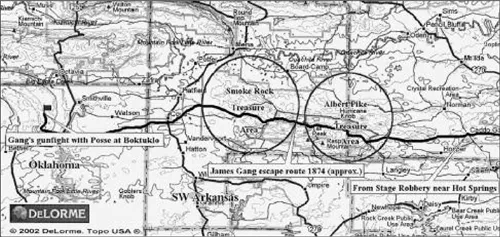

With settlement came the stagecoach. This, in turn, pulled in the out-law gangs, which used this great Southern range—stretching east to west from Little Rock to Atoka, Oklahoma—as a springboard for some of their dramatic raids. Jesse James was reported to have ridden through the Ouachita hills following a stagecoach robbery near Hot Springs, Arkansas, in 1874. Then, the ill-defined border area between frontier Arkansas and the Indian Nations territory to the west was a haven for every fugitive from justice, giving rise to the maxim, “There is no law west of Little Rock, and no God west of Fort Smith.”

It was these images of the untamed woods that captured the imagination of nine-year-old Bob Brewer, back in 1949. Tiny Hatfield—population 300—had been home to generations of Brewers before him. Many of his forebears had figured in the growing wave of westward migration from Kentucky in the mid- to late-1800s. Most, like his paternal grandfather, William Brewer, a Kentucky-born teacher turned cotton farmer who would become mayor of the town, decided to stay in Hatfield for most of their adult lives. Bob’s father, Landon, sought adventure for a time beyond the timbered hills, but, in the end, succumbed to the pull of the Ouachitas.

In 1949, after a long career as a naval officer, capped by several years at war in the Pacific, forty-one-year-old Landon Brewer moved his family to the bluffs of Arkansas’s Polk County from his latest posting on the outskirts of San Diego, California. It was time, he sensed, to return to the interior, to the soil, after a two-decade hiatus. For Bob, who loved reading Jack London, Mark Twain and tales of outlaws and treasure, the Arkansas hill country held out enormous possibilities. And none too soon. Life as a Navy brat on the fringes of the city had long lost its luster.

Young Bob swiftly embraced the surrounding Ouachitas. The pristine two-million-acre forest of red oaks, white oaks, beeches, hickories, maples, hollies, shortleaf pines and Eastern red cedars seemed a boundless playground. Life was suddenly distilled to its simple pleasures and truths. Whatever light penetrated the thick foliage was good enough for him; whatever steep trail let him navigate two-thousand-foot elevations was just added sport. The same could be said for dodging rattlesnakes, copperheads and the occasional feral hog. Ticks, chiggers and poison oak abounded, but Bob regarded them as minor nuisances.

To Bob, the mountains and the dense deciduous forest were not the least bit threatening. They were inviting, nourishing—clear streams teeming with fish; seasonal yields of hickory nuts, black walnuts, wild huckleberries, blackberries, cherries and muscadine. The Ouachitas, he sensed, were materially and spiritually tied to his parents’ backwoods past. A child who had known his father only as an infrequent visitor during the war years and his mother as a dutiful career Navy wife, Bob began to grasp what his parents had meant by settling down and “going home.” It was a phrase that he had heard many times.

1. Escape route taken by James Gang after an alleged September, 1874, Hot Springs, Arkansas, robbery.

When Landon and Zetta Brewer finally bought an old two-story farmhouse in the rolling hills around Six Mile Creek near Hatfield, they made a pact to leave the transient lifestyle of a twenty-year military career behind. They knew there would be a period of adjustment for their three sons and their daughter in downshifting to a thumbnail town with little more than a school, a few churches, a couple of stores and a post office. Still, the rustic Arkansas backcountry near the headwaters of the Ouachita River would offer a simple, unencumbered existence that would set their kids on the right path.

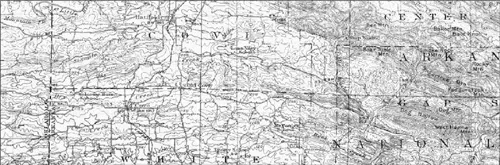

2. Close-up topographic map of Polk County, west-central Arkansas, showing Ouachita range and the towns of Hatfield and Cove, along with Smoke Rock Mountain, Six Mile Creek and other landmarks central to Bob Brewer’s upbringing in the wooded hill country.

But the woods that blanket the Ouachitas have their own special temptations and distractions. It was only a matter of months before Bob’s simple life would become very complex.

In the rugged mountains along the Oklahoma border, which include the better-known Ozarks to the north and the Ouachitas to the south, kin can run as thick as the trees. Extended families, with a bewildering number of relatives residing within a few miles of each other, are common. After the Brewers’ arrival in Hatfield nearly a hundred cousins, aunts, uncles and friends showed up for a reunion. Afterward, Bob barely could put faces to names, except for two imposing figures, forty-year-old Odis Ashcraft and Odis’s spry, seventy-four-year-old father, William Daniel Ashcraft, whom everybody, including the Brewers, called “Grandpa.” Both “Uncle Ode” (the husband of Landon’s sister, Bessie) and “Grandpa” Will Ashcraft had taken a special liking to Bob and his brothers the few times that the Brewers had visited Hatfield during Landon’s military service. The feeling was reciprocated by the Brewer boys, who saw in these tough, lean, laconic woodsmen the personification of the mountaineer.

Grandpa Ashcraft was a powerful and revered figure, both in the family and within the tight-knit Hatfield community.1 Having arrived in the valley in 1907, Kentucky-born W. D. Ashcraft spent his early years raising livestock and helping transform Hatfield into the cattle- and hog-trading center for Polk County. He also trapped and hunted, selling some of the furs. During the Depression, he was known to have distributed freshly killed game to families struggling to put food on the table. And there were rumors of moonshine being made in the hills.

Later in life, Grandpa’s occupation was not so easily defined or understood. W. D. Ashcraft took to the woods nearly every day on horseback, from sunup to sundown and sometimes through the night, with his well-oiled rifle tucked neatly into his saddle scabbard. On one occasion, he went off knowing full well that his pregnant wife, Delia, had gone into labor at home, delivering one of the couple’s thirteen children. “You little, short-legged sonofabitch! You just get on your horse and leave me with all of your kids!” she had screamed, but to absolutely no effect, family members recall.

The ostensible mission behind such outings was “hunting cows,” as Grandpa would explain to family and as he would often note in his diary.2 Bob, for one, thought this odd because he had seldom seen significant numbers of cattle on his great-uncle’s property. He would discover as an adult what Grandpa Ashcraft meant.

Grandpa’s diary, Bob would later learn, contained two unusual entries: “Found cow in cave” followed by the next day’s “Stayed home.” As a boy, Bob had no way of knowing that “cow” might have been shorthand for “cowan,” an old Masonic term for “intruder.”3 And while there had been rumors around the region for decades that Will Ashcraft may have killed a man or two, Bob would not become aware of them until he was well into his adult years.

Grandpa’s family lived an austere, subsistence existence—through mid-century—in a pre–Civil War log cabin lit by kerosene lamps and devoid of plumbing, some ten miles from the Brewer farm. But no one within the Ashcraft clan ever seemed to complain, even though the small cabin—with its more than a dozen inhabitants—had but one or two windows and only a few beds. The Ashcrafts were self-sufficient and always seemed to have whatever basic food supplies—garden-grown vegetables and fruit, salted pork, wild hog, deer, squirrel and raccoon—and clothing they needed. Drinking water came from a spring next to the cabin. Heat was provided by a mud-and-stone fireplace and a wood-burning stove. The real mystery for the family at large was the grizzled mountaineer’s orthodox devotion to the woods: he was hardly ever at home.

For Bob and his brothers, visits to the rustic cabin along Brushy Creek and to Uncle Ode’s house nearby were limited to weekends during the school year. But after school let out in May, and the crops were planted, the Brewer boys’ visits extended into weeks at a time. Now that the family had reestablished roots in the Brushy Valley, there would be plenty of time to learn the ways of the mountains: logging, prospecting, hunting, trapping, fishing and horsemanship.

Within days of school’s shuttering for summer in 1950, Bob, his older brother Jack and his younger brother Dave climbed onto Uncle Ode’s wagon for a logging haul far into Brushy Creek’s interior. Grandpa, in the front seat, handed Bob the reins, and the youngster quickly took command while Odis looked on from the rear.

The idea of steering a mule-drawn wagon across mountain trails was so exciting that Bob almost missed Grandpa’s casually spoken words. “Bobby, see that ol’ beech, there along the creek?” the old man said, pointing to a sturdy tree with soft, dapple-gray bark and dark green almond-shaped leaves. “That’s a treasure tree. It’s got carvings on it that tell where money is buried.” Bob, his eyebrows arched, stared intently at his great-uncle, seeking elaboration. All he got was a stern gaze from the old man. As the wagon rolled on, Will Ashcraft pointed toward a narrow hollow abutting Brushy Creek. “That’s where a Mexican is buried. Somebody found him messing where he shouldn’t have been messing and shot him.” This time, Bob pressed him with questions, but the mountaineer would say no more. He simply told the Brewer boys to jump out of the wagon and get busy with the log-splitting job ahead. W. D. Ashcraft had a reputation for being more than demanding—he was outright tough.

In the silent moments that followed—and they were silent, for the Ouachitas are a place where youth show respect for elders and do not ask many questions—something began to stir within Bob’s head. What had Grandpa been talking about? The woodsman’s words were deliberate, premeditated, meant to sink in. And they did just that. The education of a Confederate code-breaker had begun.

During the next few months, the theme of buried treasure filtered through Bob’s new life in the Arkansas forests. References to hidden gold were sporadic, always oblique and never satisfying. He sometimes overheard talk of “mining claims” among the Ashcrafts and two of their neighbors, brothers Isom and Ed Avants, descendants of John Avants, who had moved into the Brushy Creek valley right after the Civil War.4 And he sometimes observed mysterious visitors talking with Grandpa or Uncle Odis—rugged men who would unravel tattered topographic maps on the hood of a truck and ask the Ashcrafts for help in finding certain spots.

Then there was Grandpa’s padlocked chest in the cabin’s kitchen. Bob would sit atop the chest and read the old man’s complete collection of National Geographic magazines. Once, he asked Delia Ashcraft what was inside. “That’s Grandpa’s. I don’t ask and you shouldn’t either,” she scolded. (It would take another fifty years before Bob would learn of the contents.)

In his forest ramblings—whether helping Ode on logging excursions, collecting firewood, hunting game, or exploring old mine shafts—Bob occasionally stumbled across what by then he recognized as treasure signs. Over time, a menagerie of inscribed animal figures—horses, snakes, turtles, birds, turkey tracks—and a collection of cryptic lettering, dates and other abstract engravings revealed themselves on beech bark or rock faces along faint forest trails. Between bites of homemade biscuits with eggs and ham—his usual lunchtime meal when working the hills—he would ask Ode about the obscure, coded guideposts. But Ode would just offhandedly confirm that what Bob had observed were in fact encrypted treasure markers and not idle graffiti.

It was as if a scavenger hunt had been laid out but no one had explained its rules or purpose. Yet Bob knew that it was not a joke, a tease, a gimmick. It had to do with family: Grandpa and Ode were aware of some dark mystery, while Landon Brewer, who had a warm relationship with his sister Bessie and his brother-in-law, seemed detached from, if not completely ignorant of, the intrigue.

Bob, who conversed little with his taciturn father, decided that it was best to keep his knowledge of the woods and its secrets to himself. The challenge was to absorb more, however, and whenever, he could. If the opportunity presented itself to take a break from schoolwork and the demanding chores around the farm, he would head off on foot or horseback to Aunt Bessie and Uncle Ode’s place on Brushy Creek. His aunt would have her biscuits, jams and fresh goat’s milk at the ready, and Ode invariably would offer up some entertaining enterprise outdoors. Odis Ashcraft had no children of his own, but he loved kids. Over time he made the Brewer boys, particularly the irrepressibly curious Bob, feel like his own sons. There was one other thing, Bob sensed: Ode was testing him.

The test was not whether he would become a true mountaineer. That was all but assured. Ode, a logger by profession, quickly discovered that Bob had a keen and growing knowledge of the trees and plants in the forest, their value to the logging industry, their medicinal properties and their place...