- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

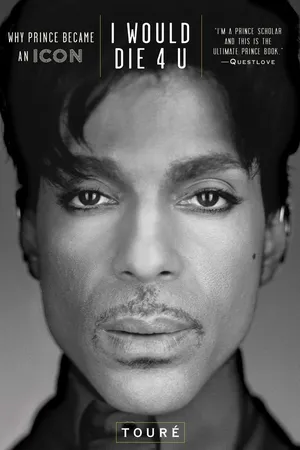

An expansive and insightful exploration of one of the most iconic and electrifying artists ever, this book reveals the stunning, multi-generational influence and appeal of Prince and his revered music—from celebrated journalist, author, and host of the popular podcast The Touré Show.

Infused with Touré’s unique pop-culture fluency, I Would Die 4 U is as passionate and radical as its subject matter. Building on his lifelong admiration for Prince’s oeuvre and interviews with those closest to the late artist, including band members, his tour manager, and music and Bible scholars, Touré deconstructs the life and work of the enigmatic icon who has been both a reflective mirror of and inspirational force for America.

By defying traditional categories of race, gender, and sexuality, but also presenting a very conventional conception of religion and God, Prince was a man of profound contradictions. He spoke in the language of 60s pop and soul to a generation fearing Cold War apocalypse and the crack and AIDS epidemic, while simultaneously being both an MTV megastar and a religious evangelist. He creatively blended his songs with images of sex and profanity to invite us into a musical conversation about the healing power of God and religion. By demystifying Prince as a man, an artist, and a cultural force, I Would Die 4 U shows us how he impacted and defined a generation.

Infused with Touré’s unique pop-culture fluency, I Would Die 4 U is as passionate and radical as its subject matter. Building on his lifelong admiration for Prince’s oeuvre and interviews with those closest to the late artist, including band members, his tour manager, and music and Bible scholars, Touré deconstructs the life and work of the enigmatic icon who has been both a reflective mirror of and inspirational force for America.

By defying traditional categories of race, gender, and sexuality, but also presenting a very conventional conception of religion and God, Prince was a man of profound contradictions. He spoke in the language of 60s pop and soul to a generation fearing Cold War apocalypse and the crack and AIDS epidemic, while simultaneously being both an MTV megastar and a religious evangelist. He creatively blended his songs with images of sex and profanity to invite us into a musical conversation about the healing power of God and religion. By demystifying Prince as a man, an artist, and a cultural force, I Would Die 4 U shows us how he impacted and defined a generation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access I Would Die 4 U by Touré in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Music Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Prince’s Rosebud

PRINCE WAS BORN IN 1958, so he is a baby boomer. However, he did not demand boomers learn a new cultural language in order to understand him, as Run-DMC and Nirvana would. Prince validated their musical taste and knowledge, which they appreciated, just as Adele succeeds, in part, because of an older audience that remembers 1960s soul, or Lady Gaga, partly because of an audience that fondly recalls Madonna. But boomers do not make up the majority of Prince’s audience, simply because they were a bit too old when he hit his stride. Many gen Xers were in their teens and early twenties during the period of Prince’s largest commercial and cultural success—from 1983’s 1999 to 1992’s Symbol. During that time, the vast majority of boomers were over thirty and, after the age of thirty, most people stop being obsessed with pop culture in the way that those between fifteen and twenty-five often are. Music is constructed for and driven by that age range: fifteen-to-twenty-five-year-olds are more likely to buy albums, concert tickets, and merchandise because, for them, musical icons often become part of their way of shaping or expressing who they are or who they want to be. Sociologists say people aged fifteen to twenty-five are in active identity formation mode, as opposed to thirty-somethings, who have a stronger sense of self and look to popular culture far less to help express and shape themselves.

Cultural icons also aid peer bonding among teens and emerging adults (people in their early and mid-twenties). Part of why we like certain artists is that we like the other people who like them, we enjoy being associated with or attached to those people, we want to be in a tribe with them. After thirty, that social transaction is less valuable, largely because the most important tribe for that point becomes the family and/or work community. Of course, that doesn’t mean that all people over thirty shun popular music, they certainly don’t, but the majority of Prince’s audience during his commercial and cultural peak were the gen Xers, for whom he was like a knowing big brother helping them define who they want to be in the world. He was just old enough to know the sixties and just young enough to understand gen X. Even given his prodigious talent, had Prince launched his message in a different time, it would’ve have been received differently, because it would have fallen on ears sculpted by divergent experiences, and shaped by dissimilar worldviews. Prince and gen X clicked on a deep level because they were made for each other.

Steven Van Zandt from Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band once told me, “Nothing is inevitable.” He meant no artist is so talented and no song is so perfectly written or sung that you can just put out that artist or that song and watch people gravitate to it like bees to flowers. It always takes more than talent: Entertainment isn’t a meritocracy. Van Zandt was making an argument about the necessity and importance of managers in music. He said the Beatles would still be in Germany and the Stones would have been playing dinner theaters, if not for great, visionary managers who helped sell them to the world. The same can be said for generations. No icon is so talented that they don’t need the right generation to receive their message. Of course, some icons transcend their time, but that’s nearly impossible without first connecting deeply with the generation that’s consuming culture when you’re at your peak. The difference between being famous and becoming an icon is, in part, having the good fortune to have a generation that’s interested in your message.

We can get a glimpse of how Prince might have been received by many boomers from the response he got when he opened for the Rolling Stones in Los Angeles at the Memorial Coliseum on Friday, October 9, and Sunday, October 11, 1981, during the Dirty Mind era: He got booed off the stage. Twice. Matt Fink played in those shows. “Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were enamored with Prince,” Fink recalled, “and they felt he was someone who should be introduced to a huge audience, so they requested his presence as a warm-up act. It was after Dirty Mind, going into Controversy, and they wanted to give his career a boost and introduce him to mainstream rock-and-roll fans and people in their circle of fans. So, we were brought on board to perform at two shows at the Los Angeles Coliseum. Ninety thousand people, sold out. The lineup was The J. Geils Band, then Prince, then George Thorogood and the Destroyers, and then the Stones.” This must have been a huge compliment to Prince, who thought a lot about Mick in the early days. Dez Dickerson said, “The one thing he talked to me about a number of times in the early going was he wanted he and I to be the Black version of the Glimmer Twins. To have that Keith and Mick thing and have a rock ’n’ roll vibe fronting this new kind of band. That’s what he wanted.”

Fink recalled: “We went on when the sun was still up, I think we hit the stage around six or seven at night, we were supposed to do a half hour or forty-minute set, tops. We get on stage and within two minutes of the first song the audience, which was a hardcore hippie crowd, they took one look at Prince and went what the heck is this? And they started booing, flipping us the bird, I’d say out of the first sixty rows of people, 80 percent of them were flipping us the bird. And they’re throwing whatever they could get their hands on. So, here we are being pummeled with food. I got hit in the side of my head with a crumpled up Coca-Cola can. I saw a fifth of Jack Daniels whiz by Prince’s face; must’ve missed his face by less than a quarter of an inch. That scared the bejeezus out of him and three songs into his set he walked off stage in a bit of a panic, some fear going on there. And he did not signal us to stop playing, he just walked away and left us there, so Dez had to signal the band and get us to leave the stage. After we got off the stage there was some confusion and we said where did Prince go? They said he took off. He got in the car and he left. He flew back to Minneapolis and made the decision not to continue on with any more shows with the Rolling Stones.” Ironically, Prince walked off during “Why You Wanna Treat Me So Bad?” which clearly had a different meaning that night. Jagger called Prince and begged him to come back and do the Sunday show. There was a lot at stake—there were several more shows scheduled in other markets. Jagger told Kurt Loder of Rolling Stone, “I talked to Prince on the phone after he got cans thrown at him in L.A. He said he didn’t want to do any more shows. God, I got thousands of bottles and cans thrown at me. Every kind of debris. I told him, if you get to be a really big headliner, you have to be prepared for people to throw bottles at you in the night. Prepared to die!”1 Dickerson told Prince he’d played in racist biker bars and had been attacked even worse. He told Prince, “You can’t let them run you out of town.” Prince flew back to Los Angeles for the Sunday night show. It did not go better.

Once again, bottles and food were thrown. Dickerson recalls a bag of old, smelly chicken pieces flying at the stage. It was obvious the audience had contempt for the funky little man who dressed androgynously and sated too little of their macho-rock needs. Prince told Robert Hillburn of the Los Angeles Times, “I’m sure wearing underwear and a trench coat didn’t help matters but if you throw trash at anybody, it’s because you weren’t trained right at home.” He was incensed by the scene. “There was this one dude right in front and you could see the hatred all over his face,” Prince told the Los Angeles Times. “The reason I left was because I didn’t want to play anymore. I just wanted to fight. I was really angry.” Fink recalled, “Prince said, ‘This is absurd. Why should we put up with that? Those are people who’ve grown up with the Rolling Stones and just look at my image in a multiracial group and me in my high heels and thigh-high stockings, bikini briefs, no shirt and a trench coat. This is enraging them and I’m not going to put up with it.” Fortunately, for history, he didn’t need to. Perhaps if Prince had arrived ten years earlier, or if we could somehow put him in a time machine and release him in a previous period, maybe he would’ve gotten that same cold response from other audiences. Maybe he would’ve been only as big as Rick James instead of becoming one of the seminal figures of his time. Maybe, as Van Zandt would say, he wouldn’t have made it out of Minneapolis. Maybe.

In Outliers, Malcolm Gladwell talks about how success is always tied to good historical timing. One example he cites is Bill Gates, who grew up at a moment when there were very few computers in society. However, there was one at his high school. He was able to put in over 10,000 hours of practice and learn how to code at a high level, thus putting him in perfect position to capitalize as personal computers became ubiquitous. Being born at that specific transitional moment in the history of computers—when he was one of the few who had access as a kid, and one of the few who had early expertise as an adult—is not something Gates controlled. It was good historical timing. That stroke of luck plus his prodigious talent led to him become a technology supernova. If he’d been born just five years earlier or later the outcome might have been different. Timing matters. Being in the right moment matters.

Gladwell could have given us the example of Michael Jackson, who was also the beneficiary of good historical fortune. As a child, Jackson was signed by Motown, which exposed him to the best imaginable music school with teachers like Diana Ross, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, Suzanne De Passe, and label founder and president Berry Gordy. When Jackson began his solo career in 1979, he did so just before the launch of MTV in 1981 and the introduction of the compact disc in 1982. At first, MTV played white rock artists almost exclusively but, over time, they bent to pressure from many sources to include Black music. Jackson’s second solo album, Thriller, arrived at the end of 1982, and was perfectly timed to become the first album by a Black artist that MTV embraced at a time when the nation was starting to transition to an exciting new sonic format called the CD. There were lots of yuppies (young urban professionals) and buppies (Black urban professionals), that is, twenty-somethings and thirty-somethings with good jobs who were flush with cash and eager to spend it. The middle class was exploding with people who’d grown up watching Jackson, and now found him making hot new music packaged on a hot new format, being lionized by a hot new music-centric TV station on which his incredibly ambitious short films played. No one in history had ever had such an amazing confluence of awesome talent, first-rate teaching, and the good fortune to unleash a great album in a strong economy while a cool, new format was being introduced and an influential new medium was captivating us. That perfect storm led to the biggest-selling album in the history of music, and it happened in large part because of several factors Jackson did not control.

When I speak of Prince’s good historical timing, what does that mean? Well, before we can understand how Prince fit so snugly within the culture of generation X, we have to unpack what that culture was. What was the Zeitgeist of the world that Prince meshed with in order to become an icon? What was the cultural weather for gen X?

When we speak of gen X, we mean people born approximately between 1965 and 1982. As of this writing, gen Xers range in age from early thirties to mid-forties. I sit toward the early middle of the group, born in 1971. People born before us, born between about 1946 and 1964, are called baby boomers. They’re now in their late forties to mid sixties. People born between about 1983 and 2001 are considered millenials or echo boomers or the net gen or gen Y. As of now, they are late preteen to late twenties. People born after 2001 are, so far, called gen Z. I’m sure that will change once they begin to assert their generational personality.

That said, these generational borders are not hard borders; they’re soft ones. Nothing magical happened between 1982 and 1983 that makes people born in those years so radically different that they must be in different camps. Researchers disagree a little on the specific years demarcating each generation, and far less on the spirit of each one. When we move away from the edge years and into the heart of the time periods, we find people whose feelings, expectations, and values are shaped by being inside the time markers of their generation. People who are in similar phases of life tend to find themselves brought together and shaped by the major historical events, social trends, technological leaps, and cultural touchstones of their time.

The size of each generation has had a huge impact on its character. The generation before the boomers, called the silent generation or the lucky few, had about 40 million people. Then, the victorious soldiers of World War II came home and found economic opportunity and widespread optimism about America’s future, which led to an explosion of births and the baby boomer generation swelled to 80 million. The massive size of the boomer generation forced America to change in response to a large influx of people, at a time of boundless American efficacy led the boomers to think they could and should change the world. If it seems that boomer needs and memories continue dominating America and the sixties remains a present part of modern culture, as if it were a kid still sitting there in the high-school cafeteria reliving the golden days when he was young and popular, even though he graduated from college years ago, well, that’s partly because there’s so many boomers in America.

In 1965, the birthrate began to fall and the generation that emerged, gen X, would end up being about 46 million people. Sociologists think the smaller size of generation X is partly because of the pill becoming widely available in the sixties and the legalization of abortion and the sharp rise in the number of working women in the seventies. In the early eighties, the birthrate began rising again, marking the beginning of the millenials, or the echo boomers, who would swell to number about 78 million. The boomers have continued their outsized impact on America by having a truckload of children. Meanwhile, the smaller size of gen X defines us, sometimes making us feel like a squeezed out middle child, overshadowed by the boomers and their romantically turbulent 1960s, and the tech-savvy millenials in a world forever changed by the Internet.

Still, demographics are an imprecise tool for nailing down the intragenerational connections we’re talking about. People do not match their generation simply because they’re born within a given range of years. A more precise way of delineating people is through psychographics, which means classifying people by psychological criteria like attitudes, fears, values, aspirations, and the cultural touchstones that mean the most to them. Looking at things through a psychographic lens allows people to be a bit more self-selective about which generational groups they fit in, and provides a sharper reasoning for why people are considered part of certain generational groups and not others, as well as why some people may share traits of two generations and why the borders between generations are soft. To get at the psychographics of generations we must explore the incidents and institutions that impact each generation. These are the signposts for the generation, or the seeds for the weather of a given generation, the things that happened to shape the shared ethos, feelings, and values of its members.

The incidents and institutions that a generation experiences en masse become the generational touchstones that bring them together and shape how its members feel about the world. For the boomers, some of the most seminal events that reflect and shape their generational character are Woodstock, the Vietnam War, and the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. These were moments that interacted with and challenged that generation’s sense of immense optimism and hope that they could unite and change the world, and they struggled to deal with them. For millenials, 9/11 was a life-changing moment that reshaped their world and taught them that America was no longer a safe place and launched a long period of distrust and fear that we still have not emerged from. The so-called great recession of the late 2000s and early 2010s has also marked millenials, launching the national Occupy movement, saddling millions with college debt and useless degrees, as well as forcing millions to live with their parents into their mid- to late twenties, delaying their ability to start careers and families. Also, everything millenials do, and the way they think, has been molded by the Internet in general and by social media in particular, as well as by texting, interconnectivity, and the pervasive ADD that comes from perpetual multitasking.

What was the seminal event for gen X? When I started writing this graf I wasn’t sure, even though I lived through it. After considerable research, I felt the truly epiphanic event for gen X was not any public event but instead one private event that happened to so many of us, that its impact reverberated onto those who didn’t experience it directly. For gen X, the seminal event that binds the generation and shapes and defines who we are and what we will become is divorce.

When generation X was young, divorce became far more common than it had been for boomers or would be for millenials. In 1960, a few years before gen X was born, there were under ten divorces per 1,000 married women. In the 1970s this number skyrockets and, by 1980, when gen Xers range from young teens to babies, it peaks at over 22 divorces per 1,000 married women. After that, as we move into the birth of millenials, the trend declines to around 16 per 1,000 by 2009. In the 1970s and 1980s, divorce touched one million children per year.

For many young people,...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Epigraph

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Prince’s Rosebud

- Chapter 2: The King of Porn Chic

- Chapter 3: I’m Your Messiah

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Notes

- Index

- Copyright