Chapter I

The Island and the Empire

On the morning of December 13, 1577, Francis Drake, a pirate and former slaver, ordered his small fleet in Plymouth, England, to weigh anchor. The ships stood out against a bleak background. They were colorfully painted, with billowing sails, and boisterous sailors calling to one another.

Plymouth lies 190 miles southwest of London, surrounded by two ancient rivers, the Plym and the Tamar, both running into Plymouth Sound to form a boundary with the neighboring county, Cornwall. It was a tranquil town, mostly farmland gathering into a peninsula jutting into a bay. Drake, from nearby Devon, made Plymouth his base of operations. The port was recognized for its shipping, and it also served as a hub of the English slave trade. It was not an innocent place. In folklore, Devon harbored witches and the Devil himself.

The fleet’s destination was unknown, but they would not be home by Christmas or even the next, not if Drake’s ambitious plan was successful. Many aboard had a financial stake in the voyage, and they might return prosperous. Or, just as likely, they might never see Plymouth again. Weeks earlier, the Great Comet of 1577 had passed overhead, an event taken across Europe as a sign, portent, or warning that a great event would soon unfold. Comets, those mysterious, phosphorescent messengers from the far reaches of space, coincided with the commencement of a new age.

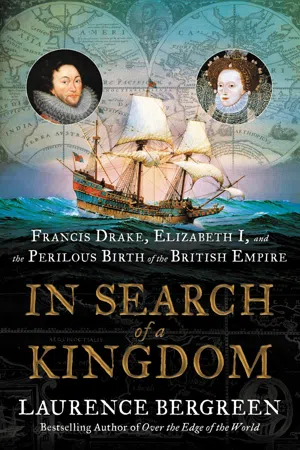

Two of the most consequential figures of this era, Francis Drake and Queen Elizabeth, knew the expedition’s true purpose: to circumnavigate the globe. If successful, Drake would take his place in history as the first captain to command his fleet around the world—and return alive. For Elizabeth, the expedition was a challenge to the global order, which ranked Spain dominant and England a second-rate island kingdom. Both dreamed the voyage would reap riches. But for the moment, Drake and Elizabeth kept their ambitions to themselves, concealing their plans for the expedition in documents.

Drake allowed the crew to think they were going to raid the coast of Panama for gold, or perhaps set a course for Alexandria, Egypt, in search of currants. These were lucrative but not exciting pursuits. Had the crew known Drake’s real intentions, they may well have deserted at the first opportunity. “The Straits were counted so terrible in those days that the very thought of attempting it were accounted dreadful,” said a commentator, referring to the treacherous passage between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, only the most obvious of many obstacles to a circumnavigation attempt. Maintaining secrecy was essential, especially from the men expected to perform the task.

The syndicate backing his voyage had authorized Drake’s fleet to cross the Atlantic, navigate the southern tip of South America, explore the west coast of that continent, and prospect for gold and silver—specifically, gold and silver stolen from the Spanish, along with anything else of value aboard Spanish ships that could be carried away. His unspoken commission was to drive out the Spanish from those mineral-rich regions. Nothing was said about a circumnavigation; it was up to Drake to take the initiative as they embarked on a journey that would transform England.

If Francis Drake ever had a moment of self-doubt, he left no record of it. He respected the violence of storms, but they held no terror for him. Drake was thoroughly at ease aboard whatever ship he happened to be sailing, from a pinnace to a flagship. He was just as authoritative and quick-witted on land as he was at sea. As a loyal Englishman, he naturally respected the queen and her court, most of them wellborn and with little use for him, but he was not awed by them. Deference did not come naturally to Drake.

Ultimately, he respected only one force in this world, and that was the Supreme Being. His father, Edmund, had come to preaching late in life, and from him Drake inherited a reliance on absolutes concerning faith. When a sailor signed on to a voyage with Drake, it was understood that he would sing psalms and recite prayers as often as possible, even several times a day. Drake ordered his crew to sing psalms before battles, to give thanks for victories, and, when necessary, to give the dead a Christian burial—and that meant a Protestant burial. Roman rites infuriated Drake, even though the two were at the time far more similar than they are now. Although rough around the edges compared with the upper echelons of the nobility, he yielded to no one in his belief in queen and country, and his disdain for her enemies, especially Spain. His was a simple moral compass, but it was durable and allowed him to negotiate the perilous straits he encountered, both real and imagined.

Drake was daring and resolute. He was short of stature, at most five foot nine, probably closer to five foot seven, and stocky. He had a typically Cornish fondness for painting and drawing. He sketched throughout his travels, the better to comprehend the Lord’s creation. Where others saw the world in muted tones, Drake saw the full spectrum. Some pirates loved women, others bloodshed and swordplay. Drake lusted for gold, and when he had stolen enough for several lifetimes, he kept on stealing it, because it was deeply ingrained in his nature to plunder. He was something of a scavenger. Everything belonged to him—potentially—at least all that glittered. He thrust himself into the world, wanting to see it all in the span of years allotted to him. He understood how short life could be, as did everyone in Elizabethan England. Plague, war, and infection frequently menaced the population, to say nothing of the hazards of sailing into the unknown. Nevertheless, the populace steadily increased: two million, three million, eventually four million over the course of Elizabeth’s long reign. Her subjects jostled for resources and for space, and so did Drake. The difference was that he had access to ships and, just as important, royal license to create mayhem in the name of the queen, and he happily rose to the occasion. With Drake, fame, fortune, and empire seemed possible, and his bravado made attaining these prizes look inevitable.

The syndicate funding Drake’s 1577 expedition included prominent Elizabethans: Robert Dudley; Christopher Hatton, the Earl of Lincoln (the Lord High Admiral); and John Hawkins. Drake contributed £1,000 from the proceeds of his previous raids on Spanish ships and outposts. Elizabeth contributed £1,000, so Drake later claimed, although no record of the transaction exists, which she would have been keen to conceal. William Winter, the surveyor of the queen’s ships, added £750. His brother George, clerk of the queen’s ships, another £500. (The sole copy of the document listing the other backers was partly destroyed by fire, obscuring their names.) Although she had not given the expedition her official blessing, the queen’s apparent participation in Drake’s syndicate signaled that it enjoyed her consent, which was almost as good. In this way, Drake’s desire for revenge against the Spanish and Queen Elizabeth’s budding need for an empire aligned.

The English fleet was led by Drake’s 121-foot-long flagship, Pelican, a galleon or multidecked ship commissioned two years earlier and built to his specifications at the Plymouth shipyards. Her beam was estimated at nineteen feet, keel between forty-seven and fifty-nine feet, and length of anywhere from sixty-eight to eighty-one feet (reports vary), with a hold of about nine feet. She was sizable, but hardly overwhelming, probably the largest ship that Drake could afford to build with his loot as a pirate. She was originally called Francis as an indulgence, but Elizabeth preferred to name the ship Pelican, after one of her personal symbols. In the allegorical medieval bestiary, a pelican symbolized Christ, wounded by humanity’s sins. The pelican flew with its breast open over the sea and wings outstretched, seeming to mimic Christ’s death on the cross. If Pelican hinted at Elizabeth’s involvement, the name of the “vice admiral,” Elizabeth, revealed the expedition’s pedigree. Elizabeth, though smaller, was a more impressive craft than Pelican: eighty tons, fashioned from wood taken from the queen’s personal stock, with eleven cast-iron cannon.

The rest of the fleet included a barque, Marigold; a flyboat, Swan; and two pinnaces, Benedict and Christopher, the last of which Drake owned. (A pinnace signified a light boat such as a tender, and also happened to be Elizabethan slang for “harlot.”) The crew came to 164, including soldiers, sailors, and apprentices, as well as a dozen “gentlemen.”

Although Drake was the captain, he did not belong to that exalted social rank. But he was unquestionably Protestant and loyal to the queen, and his years of experience in the company of Hawkins, as well as his own daring exploits, testified to his courage, resourcefulness, and skill as a mariner. And the ships arrayed before him would make his ambitions attainable.

Their provisioning was, by the standards of the time, ample: biscuit, powdered and pickled beef, pickled pork, dried codfish, vinegar, oil, honey dried peas, butter, cheese, oatmeal, salt, spices, mustard, and raisins. (Nearly all these items were provided by Drake’s longtime Irish supplier, James Sydae.) Scurvy—the loss of collagen, one of the body’s building blocks—devastated sailors, and not until 1912 would it become widely understood that ascorbic acid, or vitamin C, available in citrus, vegetables, and beer, prevented it, yet even at this early date, English captains including Drake relied on oranges and lemons as a remedy without understanding why they worked.

English sailors were known for drinking quantities of ale and wine, but the record is silent concerning the expedition’s supply of alcohol. More is known about the objects Drake brought along for trading, including knives and daggers, pins, needles, saddles, bridles, bits, paper, colored ribbons, looking glasses, cards and dice, and linens. Carpenters packed staples such as rosin, pitch and tar, twine, needles, hooks, and plates, together with pikes, crossbows, muskets, powder, and shot. Drake himself was fond of luxury items, including perfume (a necessity in an age of negligible hygiene) and dishes made of silver with gilded borders, embossed with his coat of arms.

For navigation, Drake relied on a Portuguese map of the globe as well as a detailed chart of the Strait of Magellan. He carried a copy of the famous account kept by Ferdinand Magellan’s chief chronicler, Antonio Pigafetta, The First Voyage Around the World, and consulted it as a guide for both navigation and the management of mutinous sailors. The young Venetian had traveled with Magellan, been at the right hand of the captain general at that fateful hour in Mactan harbor, and was fortunate to be among the handful of survivors of the voyage. His account made it clear that everything—even survival—came with difficulty for Magellan, who perished in the Philippines. It stood as a reminder that attempting to cross the Atlantic, let alone sail all the way around the world—ever changing, poorly understood, and immense—was more than dangerous, it was fated to end in disaster and oblivion. Those drawn to it were likely to be reckless, fearless, and rapacious. They had little to lose and perhaps fame to gain.

Books about the New World were a new and expanding genre at the moment, and Drake brought several state-of-the-art volumes with him, including L’Art de naviguer, published at intervals between 1554 and 1573. This work was a French translation of Pedro de Medina’s authoritative Arte de navegar, originally published in eight volumes in Valladolid, Spain, in 1545, and dedicated to the future king of Spain, Philip II. Then there was Martín Cortés de Albacar’s Breve compendia, published in Seville and translated into English in 1561. Profusely illustrated, this was the basic text for many captains and covered technical matters such as magnetic declination (the angle between magnetic north and true north) and the celestial poles, hypothetical points in the sky where the Earth’s axis of rotation intersects the celestial sphere, a projection of the sky onto a hemisphere. These measurements were useful for a ship to fix her position when out of sight of land. Cortés also discussed the nocturnal, an instrument that allowed a navigator to determine the relative positions of stars in the night sky and to calculate tides, critical for ships in determining when to enter ports. Drake’s nautical library included two other standard references: A Regiment for the Sea by William Bourne (1574), which was a translation of Cortés’s popular work, and Cosmographical Glasse by William Cunningham, a physician and astrologer (1559).

Drake did not expect to command the expedition. The original leader was Sir Richard Grenville, a wellborn mariner from Devon who had served as a member of Parliament in addition to trying his luck as a privateer. In 1574, he had proposed to rob Spanish ships, establish English colonies in South America, sail through the Strait of Magellan, and proceed across the Pacific to the Spice Islands. At the time, Drake was attempting to put down a bloody rebellion by Irish and Scots in the Rathlin Island massacre off the coast of Ireland. Hundreds died, and Drake, who had not been paid for his efforts, moved on. Grenville received his license from the English crown, but it was later withdrawn because England was reluctant to provoke the powerful, reclusive Spanish monarch, Philip II. Diplomacy, not conflict, was the watchword of the day. Drake inherited the role that had once seemed destined for Sir Richard, who resented the redheaded upstart for the rest of his life.

The Spanish had gotten a decisive jump on England in global commerce and exploration. In July 1525, just three years after Magellan’s battered Victoria returned to Seville, King Charles dispatched García Jofre de Loaísa to explore the Spice Islands with a fleet of seven ships and 450 men, including Juan Sebastián Elcano, the Basque mariner who had sailed with Magellan and was among the few survivors. Loaísa was assigned to rescue lost ships from Magellan’s ill-fated Armada de Moluccas, but this ambitious goal proved impossible to achieve.

After weathering storms and a mutiny, Loaísa’s much reduced fleet entered the Strait in May 1526. The next leg, across the Pacific, proved devastating, as one ship after another ran aground. Santa María del Parral made it all the way to the coast of Sulawesi in Indonesia. There members of the crew were either killed or enslaved, with the exception of four survivors. Just one ship of the original seven made it to the Spice Islands. By that time, both Loaísa and Elcano had succumbed to scurvy. Their corpses were wrapped in linen and deposited in the sea. Only twenty-four men remained by the end of the voyage, and they all returned to Spain. Among them was Hans von Aachen, Magellan’s gunner, who therefore became the first person to circumnavigate the globe twice.

Later, in 1533, Francisco de Ulloa was sent from Valdivia, on the coast of southern Chile, to investigate the Strait. Ulloa thus became the first European to enter the western mouth of the Strait. He made it partway through before determining he would run out of provisions and headed back to Chile. In November 1557, Juan Ladrillero became the first explorer to traverse the Strait in both directions. And he was followed by other Spanish explorers.

Their efforts raised the stakes of Drake’s voyage. It was vital that Elizabeth establish an English—and Protestant—presence in the New World before it was too late. But Drake was not one to feel desperate or agitated. The sheer scale of the Central and South American landmass was too great for any power, even Spain, to control completely. Although it was not yet apparent, the Spanish navy was overextended, undisciplined, and indolent.

Yet Drake’s diverse crew seemed barely equal to the ambitious tasks he set for them. Only one, William Coke, had reached the Pacific, not as an explorer but as a Spanish detainee. Drake did include men skilled in crafts they would need: a blacksmith, coopers to maintain and fashion barrels, and carpenters. Drake adored music, and he included several musicians along with a selection of instruments to perform at the change of watch and to accompany the singing of psalms.

There were about a dozen gentlemen on board, notably Thomas Doughty, a nobleman and investor in the voyage, along with his younger half brother, John, also present. Thomas Doughty probably knew of Drake’s real intentions, and his status led him to think of himself as cocaptain, a dangerous delusion. The resulting insecurity unnerved Drake and affected the entire crew to the point where it would threaten the voyage.

Other crew members included a naturalist named Lawrence Eliot; a botanist; several merchants, among them John Saracold, a member of the Worshipful Company of Drapers, a powerful trade association whose origins went back to 1180.

Then there was Francis Fletcher, a priest in the Church of England, tasked with religious observance. Records indicate that he studied at Pembroke C...