This chapter illustrates trends in social media use and explores how social media is used in ways that are relevant to social work practice. Research on both adults’ and children and young people’s use of social media explores its attractions and benefits. Several studies emphasise how social media promotes self-help-seeking behaviours, relationality, advocacy and community building.

Statistics

Prior to social media, our communication experiences of public broadcast media (TV, newspapers, radio) involved our access as an audience, with broadcasters exerting little control over who was in that audience. Other media emerged that facilitated one-to-one (dyadic) communication (i.e. telephone), with group-based interactions being available but less common. Enabled by Web 2.0 and internet technologies, social media use is situated within the wider context of internet use. OFCOM (2017) reports on UK statistics on social media use, drawing on research that looks broadly at media use, attitudes and understanding, and how these change over time, with a particular focus on those groups that tend not to participate digitally. The report covers TV, radio, mobile, games, and particularly the internet and media literacy.

According to OFCOM (2017), in 2016 89% of households in Great Britain (23.7 million) had internet access, an increase from 86% in 2015 and 57% in 2006, and there was continued growth in the use of both internet and smart technologies (mobile phones and TVs) and in online purchasing. OFCOM (2017) reports that the internet was used daily or almost daily by 82% of adults (41.8 million) in 2016, compared with 78% (39.3 million) in 2015 and 35% (16.2 million) in 2006. In 2016, 70% of adults accessed the internet ‘on the go’ using a mobile phone or smartphone, up from 66% in 2015 and nearly double the 2011 estimate of 36%. New analysis on the use of smart TVs shows that 21% of adults used them to connect to the internet in 2016. In 2016, 77% of adults bought goods or services online, up from 53% in 2008, but only up one percentage point from 2015. Clothes or sports goods were purchased by 54% of adults, making them the most popular online purchase in 2016. The report also found that 25% of disabled adults have never used the internet, and that for online purchasing the speed of delivery was a problem encountered by 42% of the 16–24 year-olds who had bought online compared with 15% of those aged 65 and over.

OFCOM’s (2017) report notes an increase in older people’s (over 65 years) use of smart and social technologies. Although this usage remains lower compared to other age groups, it increased for those aged 65–74 (39% versus 28%) and for those over 75 (15% versus 8%). In addition, 20% of users aged 65–74 nominated their mobile phone as the device they would miss the most – an increase compared to 10% in 2015. Internet use is also increasingly mobile, with OFCOM reporting that almost one in four internet users (24%) only use a mobile device to go online, suggesting that there remains a preference for using laptops and standard PCs for some tasks. OFCOM (2017) also reports that while internet use is increasing overall, there are significant numbers of people with disabilities who have never used it.

Social media has revolutionised our communication channels and opportunities to the extent that we are now able to form small networked communication groups where members can post (i.e. WhatsApp), and for young people text-based communication is replacing voice-based use of the telephone (Miller et al., 2016). In terms of children and young people’s use of social media, Schurgin O’Keeffe et al.’s (2011) study found that:

- 44% of 6 year-olds go online in their bedrooms

- 28% of 10 year-olds have a social media profile

- eight out of ten 5–15 year-olds use YouTube to watch clips and programmes.

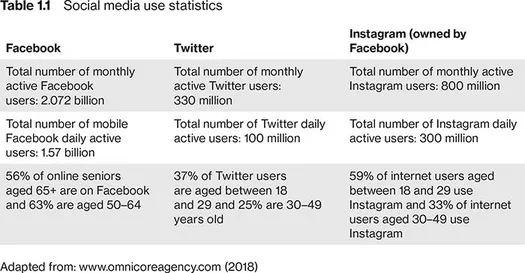

Data on social media use across several social media (and social networking) platforms is illustrated in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1 Adapted from: www.omnicoreagency.com (2018)

These statistics will undoubtedly change as social media use increases – or decreases, for example if there is reputational damage and a platform starts to lose popular appeal. However, they do provide clear evidence of the ubiquity of social media in our everyday lives and across the life span. Kuss and Griffiths’ (2011) review of the literature revealed that approximately one-third of all internet users participate in SNS and 10% of the total time spent online is spent on SNS. Kuss and Griffiths (2011) discuss several studies that specifically explored the use of social media by different age groups. They found some interesting gender differences. Men were more likely to reveal more personal information and engage in social searching (i.e. extracting information from friends’ profiles), finding this more pleasurable than social browsing (i.e. passively reading newsfeeds). Women used SNS to communicate with peers, while men used SNS for ‘social compensation, learning, and social identity gratifications’ (Kuss and Griffiths, 2011: 3534). According to Bernstein et al. (2013), social media users considerably underestimate the reach of their online posts and misunderstand who can see the information they share.

Reflective questions

Your use of social media

- How has your social media/social networking use changed in recent years?

- What accounts for these changes?

- What do you do less/more of, and what do you do differently?

Media literacy

Media literacy is defined as: ‘the skills, knowledge and understanding they need to make full use of the opportunities presented both by traditional and by new communications services. Media literacy also helps people to manage content and communications and to protect themselves and their families from the potential risks associated with using these services’ (OFCOM, 2018). Since 2005, OFCOM has conducted regular research that provides information about media use and media literacy. This includes surveys on attitudes to media and media use by adults, children and their parents as well as smaller-scale qualitative cohort studies that track media habits.

Online media literacy includes:

- Technical literacy – for example, the knowledge and skills required to use a computer, web browser or particular software program or application.

- Critical content literacy – the ability to effectively use search engines and understand how they order information; who or what organisations created or sponsor the information; where the information comes from and its credibility and/or nature.

- Communicative and social networking literacy – an understanding of the many different spaces of communication on the web; the formal and informal rules that govern or guide what is appropriate behaviour; level of privacy (and therefore level of safe self-disclosure for each); and how to deal with unwanted or inappropriate communication through them.

- Creative content and visual literacy – in addition to the skills to create and upload image and video content, this includes understanding how online visual content is edited and constructed, what kind of content is appropriate and how copyright applies to their activities.

- Mobile media literacy – familiarity with the skills and forms of communication specific to mobile phones (e.g. text messaging), mobile web literacy, and an understanding of mobile phone etiquettes. (OFCOM, 2018)

Activity

How media literate are you?

Consider each aspects of media literacy and draw on examples from your personal life or from your practice to reflect on your levels of media literacy skills and knowledge.

Identify your learning needs and think about how you might develop your media literacy skills and knowledge to inform your practice.

The digital divide

The skills and knowledge required to navigate, select and interact with technology with confidence are essential in this new digitally networked landscape, and specifically for social workers (Watling and Rogers, 2012b). Watling and Rogers (2012b) suggest that those who receive social services are more likely to experience the digital divide and so the profession should be sensitive to this when formulating ways of working with people who use social services. Digital literacy includes:

- learning skills

- ITC literacy

- career and identity management

- information literacy

- digital scholarship (academic or professional)

- media literacy. (Joint Information Systems Committee, 2015)

Digital literacy relies on people having a sophisticated and nuanced critical set of skills to create, inhabit and navigate the online world. As well as unequal access and lack of resources, age and levels of skills may also create digital divisions. ‘Digital natives’ and ‘digital immigrants’, terms first coined by Prensky (2001), were used to distinguish between confident and resistant users of digital technologies and this distinction often suggests that there is a digital generational divide: ‘depicting children and young people as technologically equipped … discounts the experiences of young people who don’t have access to technology’ (Megele, 2018: 21). White and Le Cornu (2011) distinguish between those who are confident in their use of digital technology (digital residents) and those who are starting out with technology (digital visitors). There is some debate as to whether the distinction between digital residents and digital visitors is age-related. Certainly, younger generations and those born into the Web 2.0 world have never known anything different, and using social media is commonplace, expected and facilitated through technological developments (broadband, WIFI). There may also be a disconnect between parents’ skills and their children’s skills and knowledge about using social media: ‘personal levels of digital skill are decisive in whether people are able to take full advantage of the opportunities that the Internet offers while avoiding associated harms’ (Livingstone et al., 2017: 84).

Parental mediation of the internet is more commonly practised by parents of younger children and by more educated parents who are equipped with digital skills. In terms of parental mediation strategies, Livingstone et al. (2017) report that less educated and less digitally skilled parents of 9–16 year-olds are restrictive and less active in their mediation. In addition, they are more inconsistent in rule-setting and demonstrate preference for technical restrictions (curfews on broadband use and parental controls). Parental mediation may be associated with parents’ perception of risks, and parents play different roles when supporting their children with their digital skills. Livingstone et al. (2017) report that mothers play a more communicative and supportive role than fathers, and boys are restricted and monitored less in their internet use than girls.

As noted above, it is important to recognise that although internet use is increasing year on year, there is a digital divide. The UK and other governments are ambitious to get everyone online and to address broadband speeds and connectivity issues. However, the digital divide disadvantages many sections of the population, such as those living in rural areas where broadband speeds are slow or non-existent, and excludes those who lack the digital literacy skills needed or who are unable to afford the hardware or technology. Collin et al. (2011), in their review of research on SNS use among young people in Australia, for example, found that certain groups faced persistent barriers to internet access and literacy, such as ‘Indigenous young people, those from low socio-economic backgrounds and those living in remote areas’ (2011: 14). Indeed, problematic access leading to this digital exclusion replicates other inequities and structural inequalities (Fitch, 2012).

Messages from research

‘Locked out: The smartphone deficit’

Citizens Advice Scotland (CAS) (2018), in their report Locked Out: The Smartphone Deficit, surveyed 1,200 people and found that a third of participants had never used the internet and many lacked basic internet skills. Younger people were more likely to only access the internet on their smartphones, with over a quarter (27%) of those aged under 45 only accessing the internet in this way. There were also differences in perception, skills and understanding of the internet, of which the following are examples:

- Young people were very experienced in using some apps but less experienced in the use of emails.

- Compared with only 8% of consumers in the least deprived areas, almost a third of consum...