![]()

1 To Fill the Earth: The Invention of Urbanización

Ildefonso Cerdá occupies a peculiar position in the canon of European architectural and urban history. Once a figure known to many, scholarship on this Spanish engineer certainly does not afford him the centrality that others hold. His is a position that, we are told, confirms the topographies of the ‘modern city’, more than it defines them. Nor is Cerdá a figure obscured by the canon – one whose bringing-to-light in the present may help to either confirm the dominant narratives of the past or to disrupt their contours. What Cerdá’s work offers may instead be a base on which a discourse on the relationships between urban space, infrastructure, architecture and power can be built – a nexus of processes, spaces and technologies that Cerdá compacted into the term urbanización.

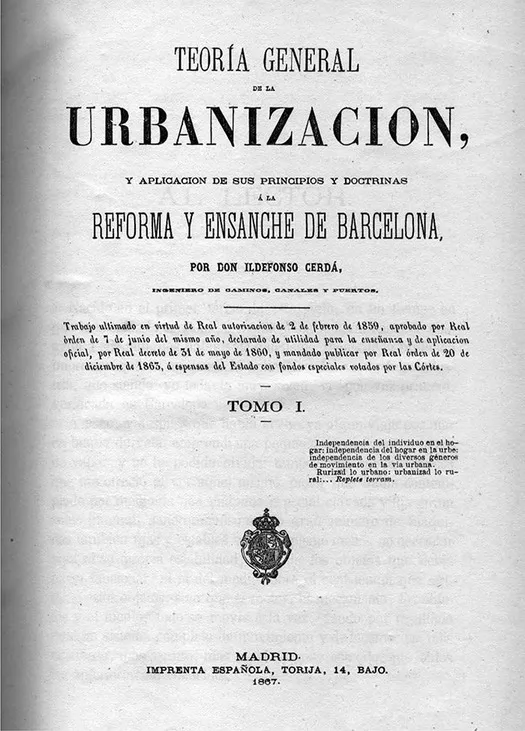

Originally designated around 1861 as a neologism by Cerdá as the basis for his monumental Teoría general de la urbanización of 1867, the term ‘urbanization’ circulated throughout Europe alongside the great urban reconstruction projects, eventually adopting its younger French derivative, urbanisme, as a more generic term for the same. By 1884, the terms appeared in English, at which point distinct meanings emerged (Cerdá, 1999: 90–2). ‘Urbanism’ came to refer to the ‘scientific’ knowledge of the city, its growth, demographic make-up, resources, and so on, whereas ‘urbanization’ generally denoted the concrete fact of the processes of the city’s growth over time. Despite their increasing centrality in popular and intellectual discourses today, urbanism and urbanization have become background terms. They are terms whose definition, meaning and history are simultaneously vague and unquestioned. Together, the terms seem to inscribe a receptacle of thought for all processes relating to the city that somehow remain beyond the realm of question. Yet they are not inactive; urbanism and urbanization have come to function as a set of universal constants – homogeneous containers inside which human action is expected to gain effective purchase on the effects of the human condition; a background of nature against which the artifice of human inventiveness can reciprocally take shape: urbanization suggests a natural, human process, and urbanism suggests the techniques by which humans can intervene in it.

Figure 1.1 Ildefonso Cerdá, Frontispiece of Teoría general de la urbanización (General Theory of Urbanization), 1867

Yet, for the author of the Teoría general de la urbanización, the notion was anything but vague. Spanning two volumes totalling more than 1,500 pages, Cerdá’s Teoría remains a vast body of theoretical speculation, which would supplement the project he is better known for, The Project for the Reform and Extension of Barcelona of 1859. Drawing together for the first time rigorous statistical and demographic assessments, historical study and, most importantly, theoretical conjecture, his Teoría would bring to bear all the scientific diligence the nineteenth-century world could muster to reconstitute the form and conception of contemporary modes of co-habitation completely. Unlike his contemporaries who were busy with the reconstruction of specific cities, Cerdá sought to create a general, universal ‘science’ of urbanization, one for which his project for Barcelona would serve as a mere prototype. The relationship between these two sides of his oeuvre remains one of the clearest and most profound in the history of modern urban thought – certainly throughout the nineteenth century – stretching from the design of sewerage fixtures to the ways in which the entire planet could be urbanized.

Despite all this, in most canonical accounts of the modern city – histories in which the terms urbanism and urbanization gain any kind of clarity – the figure of Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann and his mid nineteenth-century reconstruction of Paris form the ideological and factual centre, passing over the immense work of his contemporary, Cerdá, as only a minor figure and reducing his work to his design of Barcelona’s reform and extension. In his epic work, Space, Time and Architecture, Sigfried Giedion overlooks Cerdá altogether, while dedicating half of an entire part of the book, ‘City Planning in the Nineteenth Century’, to an examination of Haussmann’s work, stating that ‘[n]o one arose with Haussmann’s power to attempt a general attack upon the new problem of the city’ (Giedion, 1982: 775). His omission of Cerdá’s work provokes embarrassment, as many of Giedion’s more speculative remarks about the future of the city mirror those written by Cerdá a century before. Unaware of even the fundamental achievements of the Teoría, Giedion clumsily praises the foresight of Le Corbusier for suggesting, in 1953, replacing the ‘inadequate’ terms village, city, metropolis, and so on, in favour of the more modern, universal ‘agglomération humaine’ (ibid.: 858) – again, a call Cerdá made clearly in 1867. Leonardo Benevolo’s comprehensive work on the history of the city, from his 1963 Origins of Modern Town Planning (Le origini dell-urbanistica moderna; see Benevolo, 1975) to The History of the City of 1975 (Storia della Città; see Benevolo, 1980) and his European City of 1993, gives a broad and insightful historiographical account of the city. Yet he also tends to give Haussmann the privileged role in the creation of the modern paradigm, despite his awareness of Cerdá’s work. Although his intentions were to expose a link between the political and the urban, his lack of detailed knowledge of Cerdá allows him to generalize the conditions of urbanization that arose from Haussmann, concluding that ‘town-planning fell largely within the influence of the new European conservatism’ (Benevolo, 1975: 110). If broadly true, this sentiment, however, enables a traditional leftist position that pits liberal reformism against royalist conservatism – a position that, at this point, offers little help in articulating a more profound relationship between the political and the urban. For both of the aforementioned authors, Haussmann’s reconstruction of Paris is contrasted with many of the early nineteenth-century developments in London. Indeed, much of the works inaugurated by Haussmann were influenced by the various innovations already in place in London’s sewerage systems and street design, and the insinuation that the model for modern urbanization was forged out of an amalgam of the two is hard to miss. Françoise Choay’s compact volume, The Modern City: Planning in the 19th Century, reiterates this point, characterizing urbanization of the industrial era as strictly following one of two models: ‘the open city, like London, which was free for unlimited expansion, and the closed city, like Paris, bounded by ancient walls’ (Choay, 1969: 15). Despite her acute knowledge of Cerdá (Choay, 1997), and even opening with an account of his invention of the term urbanización, Choay too falls in line with the traditional narrative treating the specifics of Haussmann’s work as a generalizable template of modernity.

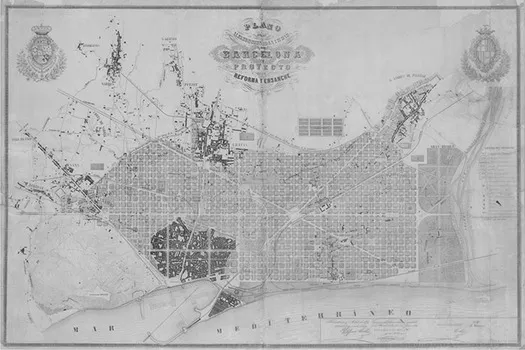

Figure 1.2 Ildefonso Cerdá, Plan of the surroundings of the city of Barcelona. Project of its Reform and Extension, 1859

Source: Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat de Barcelona. Reproduced with permission from l’Arxiu Municipal de Barcelona

Indeed, the canonical history of the modern city is a history of objects, rather than one of thought; outcomes and influences, rather than systems and power structures. That it oscillates between nineteenth-century Paris and London, suggesting concurrent forms of urbanization at work in Vienna, Barcelona, Brussels, Florence and others, should not surprise us. At times implicitly, at others, explicitly, historians and urbanists have largely accepted and continue to repeat the narrative that the history of modern urbanism began with the reconstruction of Paris at the hands of Haussmann, whether painted as villain or hero. Paris was perhaps Europe’s most important city of the time, and, because Haussmann’s work was so radical and indeed influential, other developments of urbanism tend to fall under his shadow; we are compelled to remember what influenced him and what was influenced by him. As a result, for the historians, urbanists and architects taking either term as an object of study, the history they describe tends to stress the spectacular, the oppressive and the romantic, reflecting the scandals and escapades of Haussmann and Napoleon III and drawing on the vast literature that emanated from Paris’s painful transformation. In this way, such a generalized extrapolation of the project carried out by Haussmann into a modern, universal urbanism must therefore also account for its many contradictions, its innumerable peculiarities: Haussmann’s project emerged, it must be remembered, out of an idiosyncratic political configuration1 and benefitted from an erratic and complex economic model – contingencies that shaped his project through and through and that could hardly be made universal. This may either provoke urban historians to retreat from any attempt to theorize urbanization as a singular paradigm, emphasizing instead its contingent nature, or it permits them to generalize the atypical. Furthermore, such an ingrained history also produces claims about its present. As David Harvey noted, ‘[today’s] global scale [of urbanization] makes it hard to grasp that what is happening is in principle similar to the transformations that Haussmann oversaw in Paris’ (Harvey, 2008: 30). Although this may not be entirely untrue, and the work of Haussmann is indeed influential in the history of the modern city, this convenient simplification permits a gap to propagate unnoticed within it. It is in the recesses of this gap that the foundational, theoretical work of Ildefonso Cerdá lies in obscurity.

Part of the reason for this is that Cerdá’s project, unlike Haussmann’s, remained incomplete, and he eventually left Barcelona frustrated and was consigned to poverty. The reason for this can only be understood if we recognize that the enormity of his oeuvre is not composed of several individual projects, but rather consists of multiple facets and stages of a singular, unified work, the aim of which was to thoroughly transform the very idea of the city itself. This project began not with a theoretical sketch, but rather with a political plea. In 1851, as a prominent young civil engineer, Cerdá made what would be his first impassioned speech to Parliament, lambasting the state of Spanish cities and the infrastructural backwardness that had persisted in Spain as a result of political neglect. It was a speech that set the scene for Cerdá’s lifelong critique of state politics that would underpin his subsequent work. Between 1855 and 1859, he drafted the plan for the Reform and Extension of Barcelona, on which he based his first theoretical work, Teoría de la construcción de las ciudades (The Theory of the Construction of Cities; Cerdá, 1991 (1859)). In 1861, after being commissioned to work on a plan for the reform of Madrid, he accompanied this project with a further theoretical treatise, Teoría de la viabilidad urbana (Theory of Urban Viability; 1991 (1861)).2 By 1867, Cerdá dedicated himself to what would become his magnum opus: the four-volume Teoría general de la urbanización. Only the first two volumes were published, Volume I providing an extensive ‘historical’ foundation for the concept of urbanization, and Volume II, a painstakingly meticulous statistical analysis of the actual ‘facts’ of the urbanization of Barcelona – an effort Cerdá saw as mandatory to justify the theoretical with the empirical. Alongside his efforts to plan Barcelona, which he was commissioned to do, he saw that what was increasingly necessary was to provide a unitary theoretical and, thus, universal basis on which modern society as a whole could flourish. This progress would be accomplished by employing the virtues of technology and science to construct a new conception of the city in which democracy and urbanization would proceed, hand in hand, to emerge from the ruins of political absolutism into the interconnected space of liberal universalism. As we will see, this body of texts reveals the great foresight Cerdá had in thinking about urban space, bearing concepts far more profound than the aestheticized boulevards of Haussmann and predating theories from Howard’s garden city, to experimentation in the development of linear cities, to various strategies of decentralization championed by Le Corbusier (1987 (1929)), to Ludwig Hilberseimer’s ‘Groszstadt-architecture’ (2013) and his notion of the ‘open city’ (1960), to a type of thinking that would be later described as ‘regional planning’. Even more recent tendencies such as landscape urbanism and urban agriculture can find their template in Cerdá’s theoretical proposition of ‘ruralized urbanization’, which we will discuss in the pages that follow. As Françoise Choay argued, some of the most renowned theorists of urbanization, even in the case of progressive urbanists such as Tony Garnier (1989 (1918)), Le Corbusier or Constantinos Doxiadis, endorse projects that merely replicate some basic moves and patterns of problem-solving within a framework predefined by a clearly Cerdian conception of urbanization (Choay, 1997: chap. 6).

Only recently has Cerdá’s work begun to gain recognition internationally. By the mid 1970s, after the fall of Franco’s regime, Cerdá emerged from historical oblivion through the efforts of various Spanish and Catalan architectural journals to publish and expose his work. In 1976, the Colegio de Ingenieros de Caminos (College of Roadway Engineers) launched an exhibition of his work and life. Following this, an illuminating review of his work was carried out by the architectural journal 2C Construccion de la Ciudad, which published a special issue in January 1977 dedicated to the work of Cerdá. In its most daring article, ‘Perspectiva y Prospectiva desde Cerdá: Una Linea de Tendencia’ (‘Perspective and Prospective since Cerdá: A Trend Line’), Augusto Ortíz roots Cerdá at the beginning of a history that extends through Arturo Soria y Mata, Le Corbusier and Hilberseimer (Ortíz, 1977). Directly after this publication, the Architectural Association Quarterly published an issue featuring a review of Cerdá’s work and life, exposing it to an anglophone audience for the first time. Urbanist Joan Busquets has dedicated much of his historical assessment of Barcelona to writing about Cerdá, placing his Teoría as the basis for modern urban planning (Busquets, 2006). Choay’s seminal work of 1980, La règle et le modèle (see Choay, 1997), made an extensive examination of Cerdá’s written work, placing it firmly and critically in a genealogy of Western thought on the city. Since then, the literature on Cerdá has expanded, in particular in Spain. Between 1993 and 1994, a major exposition entitled ‘Cerdá: Urbs i Territori’ was organized in Barcelona, following which Electa published an extensive anthology of Cerdá’s writing edited by Arturo Soria y Puig, an expert on the figure. In 1999, this book was translated into English and remains the single most comprehensive collection of Cerdá’s work in English to date. Most recently, Italian philosopher Andrea Cavalletti published his thesis entitled La citta biopolitica, which offered a critical account of Cerdá’s plan for Barcelona following Foucault’s work on security – a study revealing the strikingly contemporary relevance of Cerdá’s conception of the urban to modern politics (Cavalletti, 2005).

Despite these developments, Cerdá’s work continues to remain a marginal and rather reduced contribution to the established histories of the city. The recent unearthing of his vast work has produced largely uncritical, and at times completely positive, responses (with the exception of Choay and Cavalletti), in which Cerdá is cast as a socially conscious reformer concerned with equality and the working class, or as an advocate of architectural minimalism set in a geometrically rational urban grid. This is accentuated when he is compared with the conservative, imperial figure of Haussmann, seen as fighting for the interests of the bourgeoisie and bound up with the political excesses of an illegitimate empire. In such light, the uncritical embrace of Cerdá the reformer helps to perpetuate the perspective that urbanization is a ‘natural’ phenomenon that can only be tamed by enlightened, rational, socially conscious reform. Paradoxically, what is missed in the praise of Cerdá’s ‘humanitarian’ efforts to distribute political justice and economic opportunity to all classes of society is the political nature of the space he proposed itself – the radical constitution of a new, universal space of economic production and biological reproduction that would replace both the city and territory altogether. As we shall see, Cerdá’s project, unlike those of any of his contemporaries, aimed to be universally reproducible – a spatial machine embodying and specifying economic, legal, administrative and political frameworks through which to restructure the basis on which humanity is to organize itself: ‘Rurizad lo urbano: urbanizad lo rural: . . . Replete terram’.3

Cerdá’s texts are the central objects with which this chapter and the following are concerned. Although the physical extension and reform of Barcelona may be a model for urban design to this day, the actual outcome is a co-opted, reduce...