- 196 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Deborah Houlding is a well known and highly respected teacher and practitioner of horary astrology. Her original version of this book came out in 1998 but has been out of circulation for several years. Its welcome return comes in the form of a newly revised and very much updated version of the 1998 edition. The author has included an excellent Appendix on traditional terms, and a Preliminary Guide to the concept of house systems. In depth information is also given on many traditional techniques, which will prove invaluable to the astrology student. An essential source book and almost required reading for any serious astrologer.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Houses by in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

The Wessex AstrologerYear

2006eBook ISBN

97819105312041

INTRODUCING THE HOUSES:

AN HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

Mark the power of the temples: through them revolves the entire procession of the zodiac, which draws from them their laws and lends to them its own; the planets too, modify the various influences of the temples whenever they occupy realms not their own and sojourn in an alien place.

Manilius, (c. 10 AD) Astronomica, II v.960

Debate continues as to when astrology began to evolve as a formalised study of the sky. No doubt observation of the Sun, Moon and stars has held our attention since the dawn of human comprehension, but the oldest detailed records we possess of astrology being practised with some semblance of organisation are the Venus Tablets of Ammisaduqa, written in Babylon around 1600 BC. Some scholars believe the texts are copies of earlier ones made during the reign of the Babylonian king Sargon of Agade (2371-2230 BC), who is said to have employed astrologers to nominate the most fortuitous times for his projects. This is roughly the period during which the Egyptian pyramids were constructed, and it is worth considering that both of these ancient civilizations demonstrated mathematical and astronomical refinement that was unparalleled in Europe until 3000 years later.

However, contrary to what was once the prevalent view that the ancient Egyptians actively employed and developed the astrology that became the legacy of the Hellenistic world, there is little evidence to demonstrate that some of the techniques used by classical astrologers were also employed by Egyptian astrologers prior to the 4th century BC. Although the ancient Egyptians had an astute awareness of celestial cycles and events, (much of their religion and mythology was sky-based and there is a large body of evidence to demonstrate the encoding of astrological symbolism into the construction of monuments and temples), their emphasis fell more heavily upon the constellations, and they were apparently less concerned with systematic, detailed planetary observations of the standard found in ancient Mesopotamia.

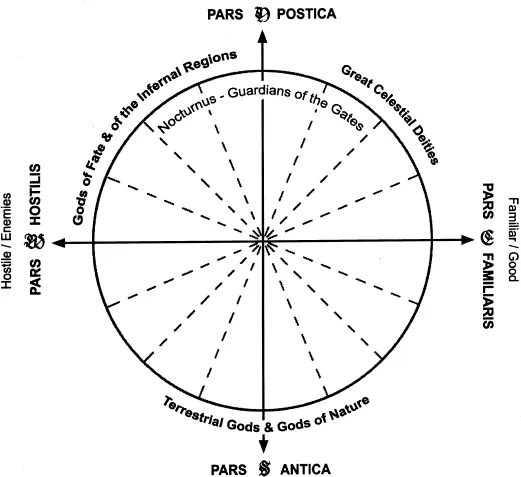

With the ancient Mesopotamians we have a more direct verification of the use of original astrological techniques that have filtered through to modern use. Their astrology was observational in nature and interpreted in a manner similar to the techniques of hepatoscopy: a very ancient divinatory practice that is well attested from the old Babylonian period (1900-1600 BC). Here the liver of a sacrificial animal was studied and meaning drawn from the shape, form, colour, distinction, direction, moisture content, clarity, curvature, location and number of blemishes and marks. A similar perspective applied to the sky was the basis of astrology: the interpretation of a star or planet was derived from its colour, luminosity, speed, location in the heavenly sphere and general physical appearance. Planetary location was related to the four cardinal points and described in terms of lying east, west, north or south; high or low; to the left or right. Each location had its own significance: one Babylonian rule was “what is right is mine, what is left is of the enemy”. Similarly east was considered a good, familiar position, while the direction west was associated with hostility and enemies. The gods of earth and nature were associated with the south, and the infernal gods were associated with the north. The direction north-west was the most inauspicious direction of all.1

Around 1000 BC detailed star catalogues were compiled in Mesopotamia, and from the middle of the 6th century BC we have evidence of the zodiac being introduced as a way of refining the measurement of planetary positions. We lack an indication that houses were in use at this time, and firm evidence of this does not appear until shortly before the dawn of the Christian era.

Most authorities believe that houses were developed at about the same time that the ascendant began to be marked upon charts, our first example of which dates to around 4 AD.2 It should be borne in mind, however, that the common practice of committing charts to perishable papyrus, and the fact that only two similar charts have been discovered from before this date, makes this information of dubious reliability. We know that the eastern horizon had been marked out by a particular star or constellation long before the use of zodiacal degrees, and we also know that the Mesopotamian culture placed great emphasis on the orientation and division of space within all of its divinatory techniques. The fundamental reliance upon the rising and setting of stars over the horizon leaves us with no doubt that the cardinal points have always been the pivotal supports for astrological interpretation, and never more so than in the astrology of the ancients where the events of most significance were witnessed around them. This is especially evident in Egyptian cosmology where the ‘two horizons’ are frequently referenced, as are the four cardinal points – each falling under the protection of its own associated god, and holding great significance in all matters relating to life and death. It would be logical to consider that some kind of structured division of the heavens was being used long before the date to which we can trace remaining evidence, both for astronomical observation and for associated mystical and symbolic purposes.

Within examples of a similar approach to spatial analysis found in liver divination, there are notable variations to what we later see in astrological house division, principally in the number of divisions, and the attributes and gods ascribed to them. However, consistency remains in the basic principles attached to spatial qualities and orientations such as left and right and east and west. The inherent qualities of these are the same as those understood by the Egyptians, the Pythagoreans, and all of the significant ancient world philosophies; where east/right is associated with diurnal, masculine qualities and left/west is regarded as nocturnal and feminine.

The techniques employed in early liver divination demonstrate this universal understanding. The symbolic must at some level relate to the physical, and the consistency exists because the meanings attached to directions are determined by meteorological influences that dictate the nature of our physical environment. Fundamentally they rest upon the shifting cycles of light and dark which creates the extremes of day and night and summer and winter, and draws association with polarities such as activity and receptivity, growth and decay. Hence the symbolic appreciation of light and colour, shape and number, and speed and direction can be witnessed as an unbroken tradition that underpins all ancient divinatory practices and which also supports the astrological philosophy of aspects and planetary meanings. The specific relevance of locations and orientations are considered further in the following chapter, and examined through the perspective of Egyptian mysticism. They undoubtedly represent the most important foundation of qualities attached to cardinal directions, upon which the specific meanings of each house developed.

Whilst the question of how much the ancient Egyptians directly established the roots of the western astrological tradition remains a controversial subject, we can at least be sure that their outlook on directional qualities mirrored that of the Mesopotamians and other early civilisations. We can also be sure that this well established and universal perspective created the primary basis upon which the later developments of Hellenistic astrology arose. By 331 BC Alexander the Great had conquered most of Asia Minor, Syria, Egypt and Mesopotamia, engulfing the entire region and making it all part of the flourishing Greek empire. Many priestly colleges along the Euphrates river valley were dissolved by the invasions, forcing priests to trade their esoteric knowledge westwards. The Greeks set up important centres of learning at Athens, Babylon, and Alexandria, (the city founded at the mouth of the Nile by Alexander the Great), and here the ancient philosophies were to have a direct impact upon each other, creating a cross-cultural intellectual pool from which the future development of science, of which astrology was seen as integral, was nourished.

With the collapse of Mesopotamia, the conquering Greeks salvaged many of her metaphysical and scientific advances, merged them with those of the Egyptians, and added their own insights to create a philosophical package which drew the wisdom of the East into the heritage of the modern western world. Alexandria in particular became an important area for the development of astrology, mainly due to its huge library, which extended to 500,000 manuscript rolls. Scholars were free to study there indefinitely supported by royal funds, a tradition which was upheld when the city later fell to the rule of Rome. Many distinguished astrological scholars, including Ptolemy and Vettius Valens, lived and studied there, and it was at Alexandria in Egypt that most of the existing astrological data was collated, re-evaluated, and re-circulated. This was done with a great desire to retain the sacred mystical principles by which the older civilisation of Egypt had masked its scientific secrets and had risen to such magnificent heights.

Around 150 BC the work bearing the names of the mythical Nechepso and Petosiris was produced in Alexandria, a treatise to which many astrological doctrines claim an origin. A further compilation of ancient texts concerning astrology, magic and alchemy was the Hermetica, written in Alexandria around 100 AD. At this time the Greek god Hermes, who had never previously been associated with learning or philosophy, was favoured with all the attributes of Thoth of the Egyptians and Nabu, the Babylonian god of divination and knowledge who was represented by the planet Mercury. Being worshipped across the three cultures as the god of learning and wisdom, Hermes became revered as ‘Thrice-great Hermes’ – the name also reflecting the belief that a god should be invoked three times. The Hermetica is reputed to have been based upon the teachings of Thoth, but it actually contains much less of ancient Egyptian origin than was once supposed and is clearly influenced by Graeco-Roman ideas. The willingness of the early authors to ascribe it to the Egyptians is assumed to be a mark of the respect afforded to this ancient civilisation and an indication of how keen the Greeks were to incorporate existing Egyptian mysticism into their own philosophical studies.

Regardless of arguments concerning at what stage and to what extent the Egyptians contributed to astrological philosophy, there is a need to recognise that many of the principles of traditional astrology, (such as use of the terms, faces, planetary hours, combustion, via combusta, and so forth), are a legacy of their world-view. In the next chapter we will see that the same may be said about the early origins of house meanings.

Firm evidence for the use of houses in chart judgements has been dated to 22 BC, with the earliest extant book to describe their meaning being the Astronomica of Manilius, written in Latin around 10 AD. Manilius displays enough confidence in his description of house meanings to suggest that he was relaying a current consensus of opinion rather than newly invented technique, whilst his general referral to the mythological beliefs of the older civilisations allows for the credible theory that house meanings were established under the influence of Alexandrian study. If so, an apt place to begin a search for their underlying principles would naturally take us to a consideration of ancient Egyptian symbolism.

2

THE ANGLES: SIGNIFICANCE OF EGYPTIAN

SOLAR PHILOSOPHY

The third cardinal, which on the same level as the Earth holds the shining dawn, where the stars first rise, where day returns and divides times into hours, is for this reason called the Horoscope, and it declines a foreign name, taking pleasure in its own. Within its domain lies the arbitrament of life and the formation of character.

Manilius, (c. 10 AD) Astronomica, II v.830

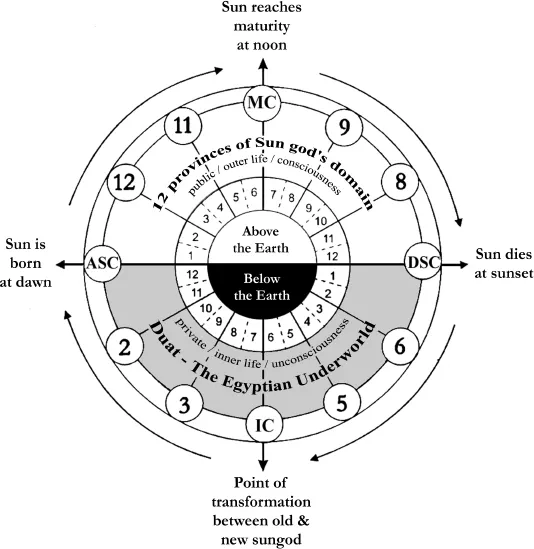

The Egyptians were strong believers in reincarnation and considered physical death to be merely a transformative process within the ongoing cycle of life. They perceived the Sun’s daily passage as a journey by which the Sun-god passed through the cycle of death and rebirth each day: dying in the evening at sunset to be born anew each morning at sunrise.

Just as the visible death of the Sun, Moon and stars occurred as they fell under the horizon in the west, the Egyptians also believed that when the soul left the body upon human death that too was pulled towards the western horizon and followed the course of the stars. Consequently the western horizon assumed a mythological connection with all aspects of death, decline, weakness and retreat. The west was known as Amentat meaning ‘the place of rest’, ‘death’ or ‘the portal of Duat’, and in reflection of this belief nearly all the pyramids and royal tombs are located on the Nile’s western bank. Conversely, the east was associated with beginnings and the renewal of life-force. Ancient Egyptian illustrations of the Sun’s passage across the sky frequently depict the Sun god ageing as the day wears on, or travelling in different boats and taking the form of different gods for each part of the journey: Khepri (whose name means ‘beginnings’) in the morning, Ra (‘radiance’) at noon and Atum (‘completed’) or Amun/Amen (‘hidden’) in the evening.

Duat was the Egyptian name for the underworld. It formed the hidden hemisphere beneath the Earth which reunited west with east. As the Sun-god continued his journey through the underworld, his cycle of transformation was completed in the centre of Duat: the nadir of the heavens, which it reached in the middle of the night. Here the completed Sun-god gave rise to a new manifestation and was transformed into a developing infant, ready to be born again at sunrise.

Associated with this belief, various superstitions and folk customs throughout the world link the cardinal direction of east with life and vitality, south with power and fruition; west with death; and north with underworld mythology. In Medieval Britain for example, places of execution were generally located to the west of the city, with graves oriented eastwards to face the rising Sun. Churchyards were located on the south or east of the church with only such people as criminals or unbaptised children buried on the north side – this lay in the shadow of the church so was considered to be a place of easy access to ‘darker spirits’.

The Lower Midheaven (IC): Fourth House

The underworld of the Egyptians was not the ‘hell’ of Medieval Christianity however. The Egyptians saw death, not as an end to life, but as a transitory stage within it: a period of purgence, rest and renewal. In ancient philosophy the ‘lower depths’ represented the Spiritual Source: the Universal Parent from which we emerge and ultimately return. Correspondingly the 4th house is astrologically connected with ‘the beginning and end of all things’, ‘parents’ and ‘the home’. Manilius wrote that it controls the foundation of all things and symbolises the deepest re...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction Wheels & Signs: Theories on House Meanings

- Preliminary Guide to Divisions of the Celestial Sphere

- 1 Introducing the Houses: An Historical Overview

- 2 The Angles: Significance of Egyptian Solar Philosophy

- 3 Aspects & Gates the 2nd/8th House Axis

- 4 Planetary Joys the 5th/11th House Axis

- 5 The King & Queen the 3rd/9th House Axis

- 6 Cadency & Decline: The 6th/12th House Axis

- 7 House Rulerships in Practice

- 8 The Problem with Houses

- 9 Ptolemy’s ‘Powerful Places’ & The Extension of House Influence

- Appendix A Glossary of Traditional & Technical Terms used in this Book

- Appendix B The Planetary Hours

- Appendix C Al Biruni’s Advice on Finding the Hour of Birth

- Works Cited

- General Index

- House Rulership Index

- Footnotes