![]()

The Information Infrastructure Era

The more energy, the faster the bits flip. Earth, air, fire, and water in the end are all made of energy, but the different forms they take are determined by information. To do anything requires energy. To specify what is done requires information.

SETH LLOYD, MIT,

Programming the Universe (2006)

Given the resources committed to them, the reverence afforded to those who own them, the adoration of the “masons” who build them, and the awe for what they house, datacenters might be called the digital cathedrals of the twenty-first century. Datacenters do deserve a certain awe. They constitute a key feature of a system that, as Greenpeace accurately observed, is the “largest thing we [will] build as a species.”

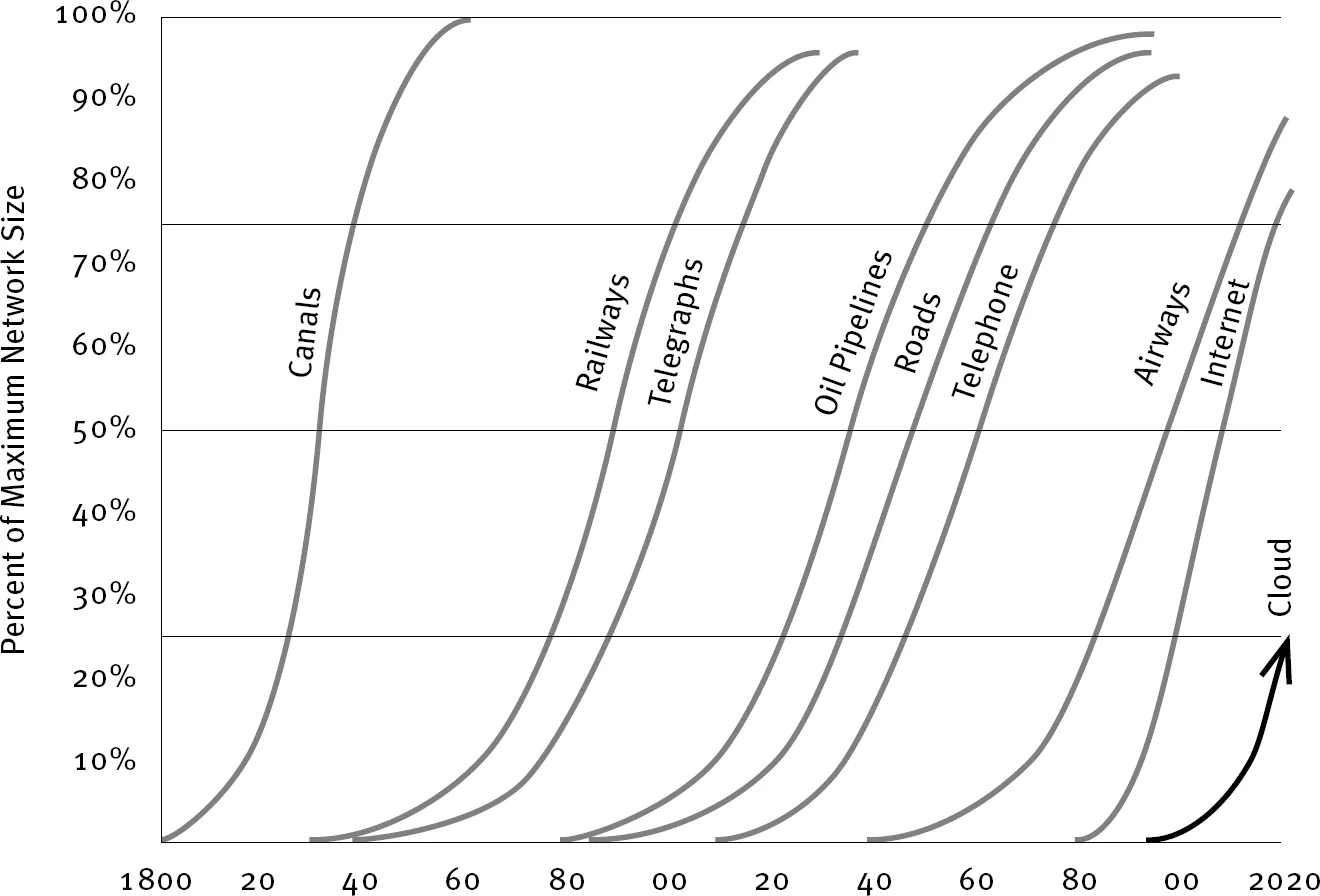

That “thing” is the Cloud, the massive ecosystem of information-digital hardware. It is society’s first new infrastructure in nearly a century.

Civilization is built on foundational infrastructures, the physical networks that provide society not just with core services, but the platforms enabling all the other features and services of a modern economy. All infrastructures entail energy and can be thus neatly divided into two general categories: those that consume energy, and those that produce it.

Only three classes of infrastructures produce energy: those responsible for food, for hydrocarbons, and for electricity. The list is similarly short for energy-consuming infrastructures: clean water, transportation, and communications. Notably, 80 percent of our economy is found in the myriad activities associated with the energy-consuming infrastructures. And now, for the first time in a century, we can add a new name to this latter list: the Cloud.

Data has been called the “new oil” and the Internet the “information superhighway.” Some analogize the rise of the Internet with the emergence of the electric age. But these analogies don’t properly capture what is now underway with the Cloud and especially its most prominent (and ineptly named) feature, artificial intelligence.

The emerging Cloud is as different from the communications infrastructure that preceded it as air travel is different from automobiles. And, using energy as a metric for scale, today’s global Cloud already consumes more energy than global aviation.

Stories about digital “disruptions” we’ve already witnessed only hint at the structural, economic, and social changes yet to come as the Cloud infrastructure expands. Indeed, most of what has happened thus far has been associated with the news, advertising, financial, entertainment, and communications industries—all of those information-centric themselves. But those activities constitute, collectively, less than 20 percent of the GDP. We are still in early days of the “digitalization” of the remaining 80 percent of the economy.

The world’s computer-communications systems now use twice as much electricity as does the country of Japan.

Uber’s disintermediation of automobile ownership and taxi use is just one example of the next phase. Everything in the non-information parts of the economy—from construction and agriculture to manufacturing and healthcare—is still largely undigitalized by the standards of, say, newspapers, advertising, and entertainment. The Silicon Valley legend Andreessen Horowitz famously said that “software is eating everything.” True. But we are only now on the appetizer course.

As we explore in the following pages the new infrastructure through the lens of energy demand, it becomes clear that we live at a time of transformation equivalent to 1919, which was three decades after cars had been invented and only a decade into the era of useful, affordable, personal mobility. The Cloud was “born” only a decade ago, and the first Internet datacenters appeared thirty years ago.

Nonetheless, today’s top five Cloud architects (Amazon, Microsoft, Google, Apple, and Facebook; there will be more) are spending over $400 billion annually—a rate rising rapidly—to build out the Cloud infrastructure. And the associated Cloud services in the United States alone (currently the epicenter of construction and investment) already constitute an $80 billion annual business, exceeding the annual revenues for all U.S. freight railroad services.

On the horizon, one should expect an array of new services that are no more imaginable today than Twitter, Uber, or Airbnb were in 1990. In due course, the Cloud, like all infrastructures before it, will evolve into a “critical infrastructure.” Policymakers and regulators will be increasingly tempted—or enjoined—to engage issues of competition, fairness, and even social disruptions, along with the challenges of abuse of market power, both valid and trumped up.

We already see governments wrestling with the disruptions to news distribution and personal privacy. One can look to history for guidance on the nature, if not the specifics, of what to expect from policymakers and regulators as new technologies continue to plow through society. The invention of radio created an entirely novel means for promulgating news, changing velocity and reach as well as profit models. Policymakers reacted by creating an entirely new regulatory regime, starting with the 1927 Federal Radio Commission that President Roosevelt expanded into the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in 1934. Similarly, safety concerns following the invention of air travel brought us the National Transportation Safety Board, an entirely new infrastructure (epitomized by the airport), and a new metric for personal travel, air-miles.

The metric used to gauge the hyperbolic growth of our digital age? Bits and bytes of data. Every 30 seconds the global Internet transports and processes a greater quantity of data than found in the Library of Congress. And both data generation and the software tools to refine that raw material are still accelerating. But analogies to libraries’ worth of data—or words like petabytes and zettabytes of traffic, or impressive trillion-dollar stock market valuations—fail to properly illuminate the sheer scale of the underlying hardware.

At the beating heart of the World Wide Web’s virtuality we find something more familiar: huge buildings called datacenters where data is stored, processed, and massaged. For real estate firms that track and monetize such buildings, they’re just warehouses filled with logic engines and digital hardware instead of, say, skyscrapers filled with people and furniture. Both add efficiency to commerce and propel prosperity, and both epitomize the dawn of their respective eras. Skyscrapers emerged at the turn of twentieth century, datacenters at the turn of the twenty-first.

Derived from Arnulf Grübler, “Time for a Change: On the Patterns of Diffusion of Innovation,” Daedalus, Vol. 125, No. 3, The Liberation of the Environment (Summer, 1996).

But datacenters utterly eclipse skyscrapers in every other measure. The power of the companies that own and operate them has already—even in these early days of the Cloud’s ascendancy—ignited both awe and opprobrium. And the quantity of capital and energy that datacenters consume is unprecedented. The world’s computer-communications systems now use twice as much electricity as does the country of Japan.

Yet, as far-reaching as the Cloud has already become, we are at the end of the beginning—not the beginning of the end—of what the digital masons are building.

Digital-infrastructure masons caught between profit seeking and virtue shaming

Six years ago Google held a conference at its headquarters’ campus entitled “How Green Is The Internet?” Other tech companies and researchers have explored this same question. It is of course a question directly derivative from the fact of the scale of the Cloud and its remarkable energy appetite. Google now reports that, since that conference, its direct use of electricity has at least tripled—a torrid growth rate typical of Cloud companies—but not typical in the rest of the economy.

Now the issue is more than just how much power datacenters themselves consume. Many Cloud companies are engaged in the debate over how society itself is fueled, and over the future of the grids that all businesses and consumers share.

Early in 2019, Google touted that for the previous two years the company had achieved “100 percent renewable energy.” This is not to single out Google; many other tech firms make similar claims, not least Apple and Facebook. The problem with such a public claim is simple reality: datacenters and the Cloud can no more run on wind and solar than an aircraft can fly by burning wood. While wind and solar energy can produce the electricity that silicon engines need, just as wood produces heat that is the essence of jet propulsion, neither can produce energy in the form that the systems actually require. An aircraft requires a high-density fuel. A datacenter requires always-on power.

Today, wind and solar together supply about 9 percent of all electricity while two-thirds comes from natural gas and coal. The latter two enable an always-on grid. Only by regulatory legerdemain or rhetorical obfuscation could one claim that any part of the Cloud is 100 percent powered by wind and solar.

How, then, do they? The regulatory “fix” is hidden in plain sight. Companies are permitted to purchase Renewable Energy Credits (not the kilowatt-hours themselves) from a wind or solar farm and then “attach” those credits to a facility somewhere else that consumes grid power which is available 24/7—not just when it’s windy or sunny. Similarly, any company can engage in a Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) to fund the construction of wind/solar farms to supply electricity to the grid, and then take credit for that green output as a kind of “offset” to the power actually consumed. (To be fair, Google does state—below the headline, literally—that its 100 percent renewable claim is based on such “offsets” and not in fact on what actually energizes its facilities.)

The “availability” of a power source is not a semantic nicety. It is a specific and critical technical feature. Any company could, whether operating a datacenter or daycare center, opt to disconnect from the grid and build an independent stand-alone green power system. The impediment is cost: building such a system to supply 24/7 power would cost nearly 400 percent more than grid power.

Exploring the claim that the overall energy economy will, or even can, undergo a near-term migration to become 100 percent wind/solar-powered is beyond this book’s scope. But note that Google’s own engineers published an analysis of renewable energy at scale which concluded that the technologies to make it competitive with conventional energy in terms of cost and availability “haven’t been invented yet.”

A single smartphone’s annual pro rata energy use—in the network, not in your hand—amounts to as much electricity as a modern household refrigerator.

As to whether our society’s grids should be radically restructured, Google asserts: “To bridge the gap between intermittent renewable resources and the constant demands of the digital economy, we’ll have to test new business models, deploy new technologies, and advocate for new policies.” Any Cloud company is welcome to try any business model, and all would be welcome to join in funding basic R&D to find new energy technologies. But advocacy for “new policies” properly falls in the public domain and intersects with countless other businesses and citizens with needs and rights pertaining to grid cost and reliability.

Regardless of how electricity is produced, however, the far more interesting story is in how the Cloud has emerged as a major and fast-growing energy-consuming infrastructure. The entire ecosystem associated with the Cloud likely already consumes about 10 percent of global electricity. And many forecasts—not just this one—see that share rising, perhaps by as much as two-fold over the coming two decades.

National debates of this kind emerge only episodically, at times when deep structural changes are underway in the economy. The age of railroads yielded consequences analogous to our time. Railroads did more than revolutionize travel and commerce while triggering the first great rise in global energy consumption; they determined where telegraph lines and oil pipelines were routed, and where and how towns and businesses were built.

The velocity and nature of railroads even spawned modern time zones and the popularity of personal watches. Rail’s reach and radical cost reductions transformed agriculture and demographics, permanently moving westward the epicenter of the nation’s “breadbasket.” Rail changed the nature of commerce itself, inspiring Richard Sears, in 1893, to create a retail giant that would last more than a century. Rail brought manifold economic and social benefits to the public, as well as outsized wealth for its architects.

Because of all that power and wealth, the railroads also generated social and political debate, riots, and massive media preoccupation with the so-called “robber barons,” an invective coined by a journalist at the time. Apropos the current debate over market and monopoly power, the most important single consequence from the rise of the rail age was that Congress, reacting to the combination of perceived and real abuses in 1887, created the first modern regulatory agency (and progenitor of all subsequent ones): the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC).

The excesses of the barons of that era, both real and imagined, were followed by excessive regulatory intrusions. By World War I, regulators had so damaged the economic and structural viability of the rail industry that, in 1917, President Woodrow Wilson nationalized it. Railroads returned, badly damaged, to private hands three years later with a phalanx of new regulations.

Analogies are never perfect, but they’re instructive. And in every era the lessons from history always seem “old fashioned” and “out of date” compared to the magic of technology of that day. We are again at a magic moment in history.

Defining structures of epochs: cathedrals, skyscrapers, and datacenters

The Middle Ages marked civilization’s first epoch of industrialization. The gear, pulley, water wheel, and windmill—and, late in that age, the clock—all propelled an unprecedented rate of economic progress and human wellbeing. This wealth and technological prowess enabled the construction of the great cathedrals—the tallest buildings that humanity had ever built to occupy. The cathedrals’ architects and masons were revered. Six centuries would pass before humanity saw a building exceed the 524-foot tower of England’s Lincoln Cathedral, completed in 1311.

The skyscraper was the icon of the next industrial revolution. In the early...