![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Leading Change to a Project-Based Organization

When all the conditions of an event are present, it comes to pass.

HEGEL, PHILOSOPHY OF HISTORY

Most future growth in organizations will result from successful development projects that generate new products, services, or procedures. Such projects are also a principal way of creating organizational change; implementing change and growth strategies is usually entrusted to project managers. However, project success is often as much a result of the organizational environment as of the skills of the project manager. As the size and importance of projects increase, the project manager becomes the head of a complex development operation with an organizational dimension that can make important contributions to project success or failure. That this organizational dimension may help explain project performance has been strangely neglected in the literature, a problem we address here by examining the role of upper management in creating an environment that promotes project success.

All too commonly, people become project managers by accident. One way to become a project manager is to ask a question at a meeting and then be told, “That’s a good question. Why don’t you take on the project of dealing with that problem?” Or somebody comes up with an idea and is tapped to make it happen, or the generator of the idea looks around for the first person in sight to whom it can be assigned for implementation. Experience indicates that in the process of developing projects, upper managers often appoint inexperienced or accidental project managers (APMs), give them a project to manage, and then systematically undermine their ability to achieve success. Upper managers do not usually undermine APMs on purpose, but too often they apply assumptions and methods to project management that are more appropriate to regular departmental management. Projects are a totally different beast in many ways. Everyday management generally is a matter of repeating various standard processes; projects, in contrast, create something new.

In addition, upper managers are often unaware of how their behavior influences project success or failure. Because previous examinations of project success focus almost exclusively on the functions of the project manager, there is an understandable lack of awareness of the importance of the project environment and the behavior of middle and higher managers in organizations—those managers of project managers whom we refer to as upper managers. It is important to understand the impact of their behavior on the future survival of organizations. Roles and responsibilities are changing as organizations become organic and project based—that is, driven by internal markets and team accountability for specific results. Any lapses by upper managers in the authenticity and integrity of their dealings with project managers and with managers in other departments are likely to have a severe impact on the achievement of project goals.

Upper managers can emulate successful gardeners: best results occur when creating an environment for systems to perform the way they innately know how to.

A Scenario

Many upper managers voice increasing frustration with the results of projects undertaken in their areas of responsibility. They lament that despite sending people out for training and buying project management software, projects seem to take too long, cost too much, and produce less than the desired results. Why is that? To help understand the problem, consider the following scenario.

An upper manager gets an idea, perhaps from reading a book or attending a conference, and has a vision of a product or service that the organization can offer. This vision may differ from what the company normally provides, so creating the product becomes a special project. Talking it over with associates, the manager is delighted when one of the best engineers becomes interested. To get the concept rolling, the manager asks this engineer to manage the project. They both figure the project can be done quickly because the engineer has achieved good results on past work. The new project manager talks to a few colleagues, and soon a team of engineers begins working on the design. After a while, the team comes back to the upper manager with good news and bad news. The good news is that a certain technology needed for the project is available inside the organization; it was developed in another division, however, so the team needs to borrow a few people from there to get it. The bad news is that another needed technology is not available in the organization, so new people will have to be hired. The upper manager arranges to borrow people from the other division and authorizes hiring the needed employees from the outside.

Delay begins about here. The new employees must be approved by the executive committee and then must have job descriptions defined and developed by the personnel department. Because these new people know the latest technology, they are expensive; even so, it takes them longer than expected to become productive once they are on board because they are not used to the ways of their new employer. Eventually, however, the whole group gets working—until a manager from the other division, for which this special project is not a priority, takes back the borrowed engineers. Work slows again as the upper manager tries to negotiate their return. Some engineers are finally freed for the project, but they are not the original engineers and thus they lack the requisite skills, which results in more delays until they are brought up to speed.

When work finally resumes, questions arise about marketing the new product and about using patented technology to create it. The upper manager must therefore add people from the marketing and legal departments to the project. Sure enough, the lawyers ascertain that the new employees inadvertently used a technology patented by another company; the upper manager must determine whether it is cheaper to pay for its use or develop an alternative technology. Communication with the new project team members from marketing is difficult because marketing uses a different email system from that of the engineering and legal departments. Decision making is further delayed as upper managers argue over a number of manufacturing issues that came up on previous projects but were never resolved.

The team grows disgruntled as it becomes clear that the great engineer is not skilled in planning and conflict management; the situation is not improved when the engineer disappears for several weeks to fix problems that arose from a previous project. Elsewhere in the organization, people begin to grumble that the project is costing lots and accomplishing little. Some do not believe the project is a good idea. The upper manager spends time justifying the project to other department managers but cannot avoid finally being called before the executive committee to explain why it is taking so long and costing so much.

If this scenario seems at all far-fetched, consider this letter that one of us received:

I work in a planning and distribution organization. My duties include leading efforts that are called projects and generally I’m fixing a problem with a process or system. Rarely do I get due dates or objectives … and when I press my sponsor[s] on this point they tell me essentially that they just want it done. Coupled with this the department has difficulty achieving the full intent of the objectives, and we are pretty unproductive (we don’t get many projects completed in a year). We are putting together a proposal including development of dedicated project managers in the organization whose entire job is to lead the projects of the organization (as opposed to the current method of choosing people whose work is closely aligned to the project).

Unfortunately, some managers feel strongly that they do not want their resources utilized by the project managers (and subject to the project manager’s discretion). Plus, they want to have access to their people to pursue their own objectives (this includes assigning one of their people as project lead[er] regardless of skill). At this point we need help in convincing these managers to support the process of project management …

You can almost hear the voice trailing off in a sigh of frustration.

Another problem is the assumption that project work should take about as long as traditional work. This sets expectations that can never be met, so projects always seem slower and more costly than other activities. Actually, they should take longer; project work represents something new and different, so the inevitable unknowns, such as those in the scenario, need to be factored into the expected length. It is also a false assumption that project work can be handled in the same way as other work, using the same organization and the same people. In reality, because project work is different, it requires a project-based organization. The project in the scenario failed because upper management had not created an environment for project success.

Creating an Environment for Successful Projects

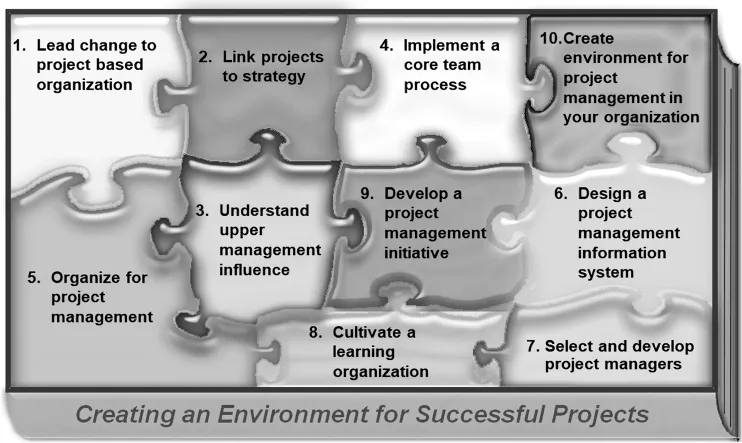

What environmental components foster successful projects? Many misconceptions develop into folklore over time, such as the Humpty Dumpty nursery rhyme (see Box 1.1). The king’s men may not have been able to put Humpty’s pieces together, but the key pieces needed to create a picture of a supportive project environment (see Figure 1.1) can be readily assembled with this book as a guide.

A word of caution: the pieces we are assembling will not stay together without glue, and the glue has two vital ingredients: authenticity and integrity. Authenticity means that people really mean what they say. Integrity means that they really do what they say they will do, and for the reasons they stated initially. It is a recurring theme in this book that authenticity and integrity link the head and the heart, the words and actions; they separate belief from disbelief and often make the difference between success and failure.

BOX 1.1 A Challenge

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall

Humpty Dumpty had a great fall

All the King’s Horses

And all the King’s Men

Couldn’t put Humpty together again.

The character in this nursery rhyme is usually represented as an egg that falls and breaks. In reality, a humpty dumpty was a type of military cannon. During a battle, it was put up on a wall. When the cannon was fired, the recoil sent it off the wall to the ground, where it came apart. The king’s horses were the cavalry, and the king’s men were the army. They were there to win the battle, but they couldn’t put Humpty the cannon together again: they were not able to put together all the pieces required for success.

FIGURE 1.1 The Components of an Environment for Successful Projects

Each of the ten pieces in the figure is the subject of a chapter in this book.

1. Lead Change to a Project-Based Organization. The balance of this chapter examines a process for changing organizations and discusses the requirements of change agents. Changing to a project-based organization requires changes in the behavior of upper managers and project managers. For example, a project-based organization must also be team based; to create such an organization, upper managers and project managers themselves need to work together as a team.

2. Link Projects to Strategy. It is important to link projects to strategy. Upper managers need to work together to develop a strategic emphasis for projects. One factor in motivating project team members is to show them that the project they are working on has been selected as a result of a strategic plan. If they instead feel that the project was selected on a whim, that nobody wants it or supports it, and that it will most likely be canceled, they will probably (and understandably) not do their best work. Upper managers can help avoid this problem by linking the project to the strategic plan and developing a portfolio of projects that implements the plan. Many organizations use upper management teams to manage the project portfolio; this approach would certainly have reduced the problems and delays depicted in the previous scenario.

Chevron, for example, developed the Chevron Project Development and Execution Process (CPDEP), which provides a formalized discipline for managing projects (Cohen and Kuehn, 1996). A key element of CPDEP is the involvement of all stakeholders at the appropriate time. In the initial process phase to identify and assess opportunities, a multifunctional team of upper managers meets to test the opportunity for strategic fit and to develop a preliminary overall plan. The project does not proceed from this phase unless there is a good fit with the overall strategy. Developing a process for selecting and managing a portfolio of projects is the subject of Chapter Two.

3. Understand Upper Management Influence. Many of the best practices of project management often fail to get upper management support. Many upper managers are unaware of how their behavior influences project success. To help ensure success, they are advised to develop a project support system that incorporates such practices as negotiating the project deadline, supporting the creative process, allowing time for and supporting the concept of project planning, choosing not to interfere in project execution, demanding no useless scope changes, and changing the reward system to motivate project work. These topics are considered in Chapter Three.

4. Implement a Core Team Process. A core team consists of people who represent the various departments necessary to complete a project. This team needs to be developed at the beginning of the project, and its members perform most effectively when they stay with the project from beginning to end. Developing a core team process and making it work are essential to minimizing project cycle time and avoiding unnecessary delays. Important as they are, however, core teams are rarely implemented well without the implicit and explicit support of upper management. Firms that have used core teams often report dramatic results. Cadillac (1991), for example, found that core teams can accomplish styling changes that previously took 175 weeks in 90–150 weeks. Developing a core team is the subject of Chapter Four.

5. Organize for Project Management. The revitalization process described in Chapter One provides the impetus in Chapter Five for determining how an organization may be changed to support proper project management. In the scenario earlier in this chapter, much of the delay can be attributed to the lack of an organizational design that supports project management. In contrast, the decentralized corporate culture of Hewlett-Packard (HP), as one example, gives business managers a great deal of freedom in tackling new challenges. Upper managers have a responsibility to set up organizational structures that support successful projects. Because structure influences behavior, Chapter Five reviews the characteristics of alternative organizational structures and examines what can be done to alleviate some of the problems caused by certain structures.

6. Design a Project Management Information System. In the past, organizational policies, procedures, and authority relationships held things together. The project-based organization lacks much of that structural framework; instead, the project organization is kept intact by an information system. For example, former HP executive vice president Rick Belluzzo (1996b) envisioned a “people-centric information environment that provides access to information anytime, anywhere … and that spurs the development of a wide range of specialized devices and services that people can use to enrich their personal and professional lives.” Upper managers need to work in concert to design information systems that support successful projects and provide information across the organization. In this regard, online technological capabilities are increasingly attractive and important but do not replace the need for upper management to determine what information is necessary and develop systems to provide it. Chapter Six covers this in depth.

7. Select and Develop Project Managers. Developed organizations will see the end of the APM. Project management needs to be seen as a viable position, not just a temporary annoyance, and project management skill needs to become a core organizational competence. This requires a conscious, planned program for project manager selection and training. HP, Computer Science Corporation, Keane, and 3M are among the companies that have spent large amounts on project manager training and development, as discussed in Chapter Seven. The development emphasis of these organizations seems just...