![]()

Part I

THE FOUR QUADRANTS MODEL: INTRODUCTION

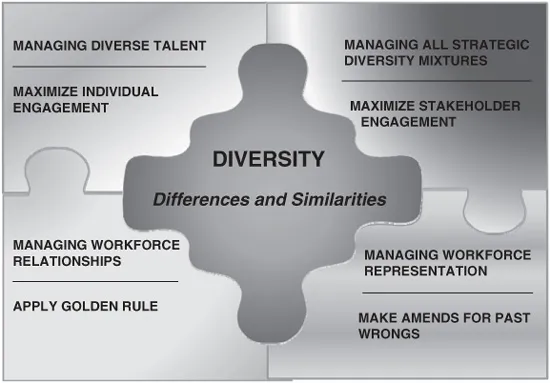

My consulting colleagues and I have been using the Four Quadrants Model for at least ten years. At first, we spoke of it as a way to capture and differentiate the various approaches to diversity. More recently, we have come to see the four quadrants as representing the four core fundamental diversity management strategies for addressing collective mixtures characterized by differences and similarities, and their related tensions and complexities. I believe that all approaches to diversity fall into one of these core strategies: Managing Workforce Representation, Managing Workforce Relationships, Managing Diverse Talent, and Managing All Strategic Diversity Mixtures.

We have dug more deeply into these core strategies to determine the paradigm or mindset that gave rise to each. This came about as we puzzled over why practitioners did not move easily between the strategies. We found the beginnings of a possible answer in the 1987 work of Judith Palmer, in which she argued that loyalty to different diversity paradigms was the basic reason for tensions between practitioners.

FIGURE PI-1. The Four Quadrants Model

Extrapolating from her work, we argued that a different paradigm undergirded each strategy and inhibited movement among them. Further, the different paradigms predisposed individuals to a particular strategy. We, thus far, have set forth four pairings and frequently have presented them as a four-piece puzzle representing the totality of the practice of diversity management. (See figure PI-1.)

In the four chapters in this part of the book, I discuss each core strategy and its undergirding paradigm. For me, these four strategy-paradigm combinations represent the areas of the diversity forest within which one can practice diversity management. I also think of these four core diversity management strategies as paths to World-Class Diversity Management capability. Part II looks at how these strategies may be actualized.

![]()

1

MANAGING WORKFORCE REPRESENTATION

Quadrant 1

CEOs and other senior executives initiated the Managing Workforce Representation strategy (quadrant) in the 1960s to address the “diversity problem” of mainstreaming African Americans into their organizations. It is one of the two original organizational diversity management efforts—and the one that most people think of when they speak of diversity. The other strategy was Managing Workforce Relationships.

In the spirit of the civil rights laws and the civil rights movement, those senior managers sought to remove barriers to having descendants of slaves involved (represented) in their organizations. They sought this representation not for the sake of diversity or for the benefit of their organizations, but rather to make amends for past injustices.

On the surface, recruiting and hiring African Americans should have been rather straightforward. Yet it wasn’t. These leaders encountered an unexpected complication. Though willing, they were unprepared and lacked experience to recruit and select African Americans for professional, managerial, and skilled positions.

Initially, it had been hoped that outlawing employment discrimination would be sufficient to trigger a rush of African American applicants. When that did not happen, all kinds of questions surfaced: Where can we find qualified African Americans? How do we attract them? How do we assess their qualifications? Are there any qualified African Americans? How do we gain a competitive edge in attracting and hiring them?

The disappointing results of desegregation made clear that additional ways were needed to make the mainstreaming of African Americans happen.

This chapter discusses Quadrant 1’s attributes and those of its underlying paradigm—Make Amends for Past Wrongs. It also explores the ways a combination of societal, legal, and moral motives and actions interacted with the motives and actions of organizational leaders to give this quadrant its characteristic qualities.

QUADRANT PARAMETERS

Definition of Diversity

A review of the literature of the 1960s and 1970s reveals clearly that mainstreaming African Americans—not achieving diversity—was the initial goal. Over the years, various equal opportunity and antidiscrimination laws and policies for achieving that goal have expanded the population to be mainstreamed to include all “protected groups,” and any others who have been missing from the workforce. When talk of diversity and managing diversity emerged in the 1980s, for many, diversity and representation became synonymous. As a result, today, most laypeople speak of diversity as if it means representation. Code for this quadrant is “the numbers,” reflecting a concern with the numerical composition of the workforce.

Goal

The original goal of mainstreaming African Americans to increase their presence (representation) in the workforce remains. However, the goal has been expanded to create a workforce that is representative of the broader society by minimizing or eliminating the underrepresentation of multiple groups that have been insufficiently present.

Motives

There are several motives for pursuing representation. One is to comply with antidiscrimination and equal opportunity laws and policies. Another is to pursue social justice and human rights in the spirit of the civil rights movement. Some collapse legal compliance and social justice–human rights–civil rights motives into corporate social responsibility. The premise here is that society expects organizations to have a workforce whose composition reflects the broader community, and that socially responsible companies will pursue this end.

In recent years, others have sought to identify a business motive for advancing representation. For me, corporate social responsibility is the strongest motive for pursuing numerical representation in the work-force. Readers familiar with my early work in Beyond Race and Gender: Unleashing the Power of Your Workforce by Managing Diversity1 may be surprised that I say this, since I then stressed the importance of the business rationale. When doing that, however, I was referring to a motive for managing workforce diversity, not for pursuing representation. I continue to believe that for managing workforce diversity, the business rationale is the stronger motive.

Focus

Historically, the greatest attention has been placed on special efforts to make amends by creating a representative workforce. This focus has translated into a lot of attention on “the numbers,” as a key measurement of mainstreaming.

Approaches

Since the 1960s, several approaches have been used to create a representative workforce. Each reflects an ongoing effort to secure sustainable progress with the numbers.

One of the first tools was the Civil Rights Law of 1964. This landmark legislation outlawed racial segregation in schools, public places, and employment. In sum, the law broadly eliminated legal sanctions for segregation. Many advocates for desegregation had hoped that the law would promote racial and gender pluralism. When that did not happen, they turned once more to proactive options—the most prominent manifestation of which has been Affirmative Action.

Affirmative Action in the United States refers to policies that take gender, race, and ethnicity into account to promote equal opportunity. The practice began in 1961 with respect to projects funded with federal funds via President John F. Kennedy’s Executive Order 10925. Subsequently, in 1965, President Lyndon Johnson—via Executive Orders 11246 and 11375—expanded Affirmative Action to require that federal contractors and subcontractors “take affirmative action to ensure that ‘protected class, underutilized applicants’ are employed when available, and that employees are treated without negative discriminatory regard to their protected class status.”2 President Johnson’s orders went beyond those of President Kennedy in that they required not just freedom from racial bias in hiring and employment practices, but also steps to ensure the actual employment of the “underutilized protected” class.

Even organizations not covered by those Executive Orders moved to adopt Affirmative Action–type policies, reflecting the relatively widespread acceptance of Affirmative Action that existed until recent years.

As Affirmative Action both gained in acceptance and attracted opponents, advocates used the benefits of the diversity that would come from effective Affirmative Action to justify its continuance. The landmark use of this justification occurred in the 1978 case of Regents of the University of California vs. Bakke. Writing for the majority of the Supreme Court, Justice Lewis Powell upheld diversity in higher education as a “compelling interest” that justified the use of Affirmative Action on the basis of race.3

My view is that by “diversity,” Justice Powell meant racial pluralism and behavioral variations; further, he assumed that representation (pluralism) would give rise to behavior variations (such as that of thought and problem solving) that would benefit the educational process. For example, he wrote that “the atmosphere of speculation, experiment and creation—so essential to the quality of higher education—is to be promoted by a diverse student body.”4

In spite of this, Affirmative Action’s focus continues to be primarily on achieving numerical profiles and not on behavioral variations. Justice Powell’s assumption—despite the arguments of the defendants—was a big leap of faith. Implicit within the assumption was that pluralism and behavioral variations are related.

Experience has demonstrated otherwise. It is quite possible to have racial pluralism without behavioral variations and vice versa. This happens when managers work to screen out possible behavioral variations, or when the representation attributes do not define the individuals in question. For example, five engineers from an engineering program—say Georgia Institute of Technology—may be racially pluralistic but behave similarly because of their engineering training.

Nonetheless, the 1978 decision linked Affirmative Action and diversity and shifted or expanded the rationale for Affirmative Action from that of solely promoting equal opportunity to also fostering diversity (pluralism and behavioral variations). This link strengthened the tendency to equate Affirmative Action and diversity, even though fostering diversity was not part of the original concept. It also led to everything in this quadrant being labeled as diversity.

The benefits argument has advanced from the educational sector to other arenas. Corporations, for instance, often subscribe to the “benefits of diversity” school of thought. In a 2003 amicus curiae brief filed with the Supreme Court, sixty-five corporations maintained that diversity provided four basic benefits in the area of employment:

1. A diverse group of individuals educated in a cross-cultural environment has the ability to facilitate unique and creative approaches to problem solving arising from the integration of different perspectives.

2. Such individuals are better able to develop products and services that appeal to a variety of consumers and to market offerings in ways that appeal to those consumers.

3. A racially diverse group of managers with cross-cultural experience is better able to work with business partners, employees, and clientele in the United States and around the world.

4. Individuals who have been educated in a diverse setting are likely to contribute to a positive work environment by decreasing incidents of discrimination and stereotyping.5

Once again, these “benefits” presume representation and behavioral variations. In practice, this may not hold true, as previous examples suggest.

Another approach or tool has been the antidiscrimination laws that came about after the Civil Rights Law and the Affirmative Action executive orders. Illustrative of these laws are the Equal Pay Act, the Age Discrimination in Employment Act (ADEA), the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the American Disability Amendments Act of 2008.6 These laws suggest why compliance is often a motive for this quadrant. Early on, they often motivated corporations and other organizations to use strategic alliances to facilitate the recruitment of minorities and women. Corporate executives established these alliances with community groups to receive assistance in identifying possible candidates for employment.

Another tool has been to establish clear lines of accountability. Until recently, many diversity programs and strategies did not address this aspect. Some very elaborate and impressive plans lacked accountability—for example, about what happens if the plan is not implemented. As this weakness was recognized, change agents called for tying diversity objectives to managerial incentives. The prevailing sentiment was “If you don’t hit them in the pocketbook, you will not get their attention or results.”

An approach closely related to the benefits tool is to connect representation to an organization’s bottom line. These efforts, however, have not been persuasive. This is in part because it is difficult to trace an enterprise’s success to one factor—diversity or what ever. In addition, social justice advocates resist the bottom-line approach, fearing that it will distract from the attention required for “injustices” that remain.

Still another approach has been to secure CEO sponsorships. Proponents of this tool argue that CEO support is critical—without it little or nothing can be done. In organizations where this thinking prevails, the first question asked is “Does the CEO support this?”

Inclusion, a recently formulated approach, means different things to different people in theory. In practice, it often means representation; so here an “inclusive organization” becomes one that has signifi-cant race, ethnic, and gender representation.

Quadrant Accomplishments

Use of the strategy of Managing Workforce Representation has enhanced awareness and acceptance of the notion that representation should exist in all sectors of society, especially with respect to race, gender, and ethnicity. This signifies an important change from the mid-1960s, when law and custom reflected a view that not everyone should be in the mainstream.

Our country and its organizations are much more representative than ever before. So much so, that in April, 2009, deliberations regarding the continuation of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Supreme Court Chief Justice Anthony M. Kennedy acknowledged “that the provision has been successful in rooting out discrimination in voting over the past 44 years. But times have changed.”7 Despite that view, the Supreme Court declined to eliminate critical parts of the act. The discussion of the quadrant’s challenges that ...