![]()

1

Management in Transition

Bridging That Divide Between

the Old and the New

Civilization today is poised at the brink of a great divide between an old way of life that is dying and a new way of life that is still being born. Behind lies an Industrial Age that lavished wealth on a world that was poor—but which also left a polluted planet, quarrelsome societies, and empty lives. Ahead lies the much heralded promise of the Information Age—but its growing contours continue to surprise and shock us. Who would have thought that a global economy would appear almost overnight? That the Soviet Union would just disintegrate? That the United States would slip into decline?1

There are many ways to examine such complex issues, but basically these are problems of managing social institutions. As a knowledge economy spreads around the world, the largest professional group today is the rising managerial class that guides a growing infrastructure of complex organizations.2 Most of the worries that dominate the news emanate from the interaction of corporations, governments, schools and universities, hospitals, news media, armies, and other institutions that support modern life. Peter Drucker described it this way: “Because a knowledge society is one of organizations, its central organ is management. Management alone makes effective all of today’s knowledge.”3

And as events accelerate to produce ever more complex technologies, intense competition, and turbulent, constant change, the aging foundation of this entire institutional system is failing everywhere. Witness antigovernment sentiment in the United States, the crisis in health care, and demands to reform education. IBM, once regarded as the best-managed corporation in the world, recorded the biggest business loss in history recently, which was soon exceeded by General Motors (GM). Confidence in institutions has fallen from 52 percent in 1966 to 22 percent in 1994, and no recovery is in sight.4

Out of all this confusion, a workable new social order must be constructed to manage a radically different world. This book describes the organizing principles that are emerging to master this challenge—The New Management—and it offers guides on how managers can lead their old institutions into this new era.

WHAT REALLY IS THE NEW MANAGEMENT?

Most people have an intuitive grasp of management because we are raised in a world of organizations, so at an early age we absorb the basic concepts of working life. That’s why management education is often dismissed as “common sense.”

But it is exactly this commonly understood sense, or “paradigm,” that is the problem. Prevailing management concepts were conceived for an industrial past, so they are not useful for a vastly different economy based on knowledge. The founding fathers of management would be baffled to hear modern managers talk of “networks,” “telecommuting,” and “virtual organizations.”

The Evolution of Management

The classic theories of Henri Fayol, Max Weber, and Frederick Taylor defined the traditional view of “mechanistic” organizations to manage the simple conditions of the Industrial Age. What could be more reasonable in an “age of machines” than to construct institutions as “social machines”? Today, however, a more complex world described by the “supertrends” in Box 1.1 has made this model obsolete.5

The force driving this transformation is the inexorable increase in computer power by a factor of ten every few years. Forty percent of American homes now have personal computers (PCs), and the number is growing 30 percent per year. The average household uses computers twice as much as it uses TV, and computers are also connecting people together through the Internet and information services like America Online, CompuServe, The Microsoft Network, and Prodigy. In 1994, the first three-dimensional virtual meeting was held across the Pacific between teams of Japanese and Americans whose images “met” in a virtual conference room. One participant described the experience this way: “We’ve been dreaming of cyberspace for a long time. Here it is, the way people really interact.” Bill Gates claims all these capabilities will be in common use by the year 2000.6

By the end of this decade, then, average people should be able to work, vote, learn, shop, play, and conduct almost all other aspects of their lives electronically, using multimedia PCs that combine the intelligence of a supercomputer, the communications of a portable telephone, and the vivid images of high-definition TV. These trends foretell a transformation of the entire social order, and the battle to define a new social order will be waged in the way we design and manage institutions.

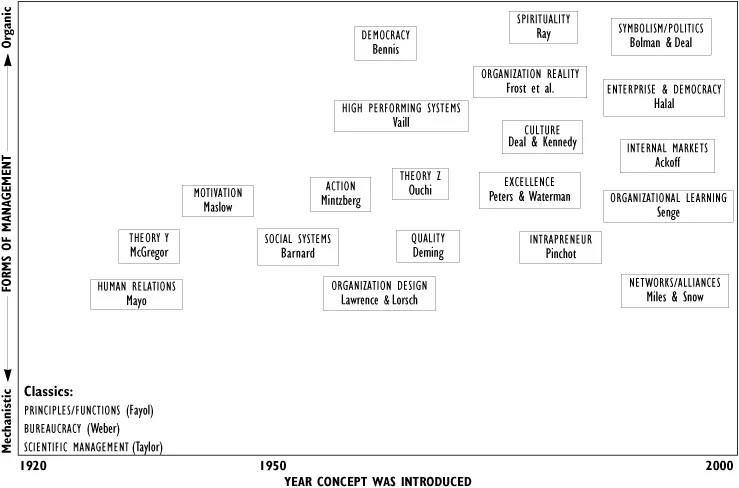

Managers have begun to restructure their organizations in recent years as Total Quality Management (TQM), alliances, reengineering, self-directed teams, empowerment, community, and other innovations suddenly burst on the scene. A recent issue of Fortune even announced “The End of the Job,”7 and Kunhee Lee, chairman of Samsung Corporation, the largest Korean conglomerate, told his managers, “Change everything except your wife and kids.”8 Figure 1.1 outlines this rich body of emerging thought, showing how the introduction of major new concepts has progressively moved the practice of management toward an “organic” focus. The entries are not exhaustive, but they offer a general guide to the rapid evolution of management today.

The neat concepts of classical management were challenged in the 1950s when Abraham Maslow, Elton Mayo, and Douglas McGregor showed that the field was expanding to include human and social factors. Later, in the sixties and seventies, bolder insights burst the boundaries of the old management altogether. Chester Barnard, an executive at American Telephone and Telegraph (AT&T), described management in terms of social systems. Paul Lawrence and Jay Lorsch discovered that effective organizations consist of diverse parts united into a coherent whole. Warren Bennis foresaw the need to replace authoritarian control with democracy. And Henry Mintzberg found that managers are engaged in an action-oriented flow of people and information rather than sterile problem solving.9

FIGURE 1.1. THE ADVANCE OF MANAGEMENT THOUGHT.

Although these were radical ideas at the time, they can now be understood more clearly as the first wave in a flood of organic concepts that swept through the 1980s and 1990s. W. Edwards Demming and J. M. Juran pioneered the quality revolution. William Ouchi, Tom Peters and Robert Waterman, and Peter Vaill helped us see that excellent managers instilled purpose and meaning. Ray Miles and Charles Snow showed that modern organizations consisted of networks. Gifford Pinchot and Russell Ackoff brought free enterprise inside the firm. Peter Senge outlined the principles of organizational learning. Terrence Deal, Allen Kennedy, Peter Frost and his colleagues, Lee Bolman, and Michael Ray revealed how institutions form their own cultures and spiritual beliefs. And my book The New Capitalism showed that all this change flows from traditional Western ideals of enterprise and democracy.10

The Old Versus the New Management

While it is clear that a new stream of management has appeared, there is great confusion over what this New Management will consist of when it matures. A quick scan of the business media shows a bewildering blur of new management ideas extolling everything from “greed is good” to “business ethics,” and an authoritative survey recently concluded that there is little agreement on today’s management paradigm.11

This confusion is particularly severe because it often rages across a great divide separating the past from the future. The economic history of our time will likely be told as a tugging and pulling between the old versus the new: power versus participation, hierarchical control versus market freedom, profit versus society, growth versus the environment, and so on.

On the “new” side of this divide, many proponents of progressive change are caught up in a revolutionary zeal that proclaims the virtues of “empowered people,” working in “fluid structures,” to serve “human needs” and “protect the environment,” all energized by “spirituality.” These are exciting ideas, but they often appear naive to managers who are struggling to survive a hard world. Managers who responded to the CIT survey offered the following reactions: “Just because an idea is old does not mean it is bad,” and “There will never be a substitute for the discipline and accountability of the old system.” One executive put it this way, “The implication that we’ve come to a crossroads in business management is full of hot air.… We need to remember, follow, and reinforce the good old ideas … no one has discovered any new secrets of management.”12

On this “old” half of the divide, it’s true that many executives are stuck in outdated views. Listen to some typical comments from managers in the CIT survey: “It is incredible to witness just how terrified senior managers are of change. They paid their dues in the old system, and now they feel a right to privileges within that system,” and “Some people must exert total control over every aspect of their business.” These are valid criticisms; however, adherents to the Old Management raise crucial objections that test new ideas, and their influence maintains a healthy continuity with the past. Serious change is going to require more than lofty sentiments.

For instance, it is refreshing to see attempts to empower employees sweep across the land, but these innovations often fail because of unrealistic expectations. Weirton Steel excited the nation when it became the largest employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) in America, yet now the company has fallen on hard times and so it has been forced to take drastic measures, including the same type of layoffs often associated with “heartless corporations.” Weirton’s owner-workers are justifiably angry: “How can we be laid off if we own the company?” asked a puzzled shareholder.13

The road to a New Management is littered with the ruins of such noble failures, so it would be wise to acknowledge their cause honestly if we want to avoid them. In the Weirton Steel case, avid proponents failed to recognize the enduring truth that “authority must be commensurate with responsibility.” While workers were enthusiastic about ...