eBook - ePub

Benefit Corporation Law and Governance

Pursuing Profit with Purpose

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Corporations with a Conscience

Corporations today are embedded in a system of shareholder primacy. Nonfinancial concerns'Äîlike worker well-being, environmental impact, and community health'Äîare secondary to the imperative to maximize share price. Benefit corporation governance reorients corporations so that they work for the interests of all stakeholders, not just shareholders.

This is the first authoritative guide to this new form of governance. It is an invaluable guide for legal and financial professionals, as well as interested entrepreneurs and investors who want to understand how purposeful corporate governance can be put into practice.

Corporations today are embedded in a system of shareholder primacy. Nonfinancial concerns'Äîlike worker well-being, environmental impact, and community health'Äîare secondary to the imperative to maximize share price. Benefit corporation governance reorients corporations so that they work for the interests of all stakeholders, not just shareholders.

This is the first authoritative guide to this new form of governance. It is an invaluable guide for legal and financial professionals, as well as interested entrepreneurs and investors who want to understand how purposeful corporate governance can be put into practice.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Benefit Corporation Law and Governance by Frederick H. Alexander in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Commerce & Droit des affaires. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Shareholder Primacy and Its Discontents

I suspect most Union Carbide shareholders would have been happy to accept a somewhat lower dividend if this allowed Union Carbide to adopt safety measures that would have prevented the deadly explosion in Bhopal, India, that killed 2,000 and severely injured thousands more.

Lynn Stout

We need to rethink exactly what we consider our wealth to be, what it is that we value, and whether it can or should be expressed only in terms of numbers and money.

Jane Gleeson-White

CHAPTER ONE

Corporations and Investors

SETTING THE STAGE

Chapter 1 provides context for the rest of the book. It includes a discussion of just what makes business entities like corporations so important to the global economy. It also explores the special privileges such entities enjoy, and the historical path that led to these privileges. Next is a brief exploration of the system through which savers channel their capital to the productive economy and of how that system interacts with corporations, which are often the final stop for capital flowing through the investment chain. Finally, the chapter raises the question whether the participants in the investment chain should have obligations to safeguard the vital systems they impact, in light of their powerful role in the economy. This question foreshadows the issue raised by benefit corporation law: Should the purpose of corporations encompass obligations to protect the systems that serve all of their stakeholders?

The Corporation

ROLE OF THE CORPORATION

This entire book is dedicated to the study of one form of corporation. The form is relatively new and still rare. As of the date of this publication, there are only five thousand benefit entities out of a total of 8 million business entities in the United States.1 Why then is the subject worthy of a book? More fundamentally, what is the significance of the distinction between benefit corporations and other entities?

Answering these questions requires an understanding of the importance of business corporations and the role they play in our economy.2 In particular, it is important to understand the relationship between corporations and shareholders, who own the equity of such entities. These shareholders provide risk capital that drives the world economy. One source estimates that publicly traded equity has a value of $70 trillion, constituting 20 percent of the “value of everything.”3

By way of comparison, the same source estimates $100 trillion in fixed income securities and another $95 trillion in real estate value.

The ability of the corporation to organize capital and apply it to areas of need has long been recognized. A leading treatise from last century described the importance of the modern corporation to industrial society:

Much of the industrial and commercial development of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries has been made possible by the corporate mechanism. By its use investors may combine their capital and participate in the profits of large- or small-scale business enterprises under a centralized management, with a risk limited to the capital contributed and without peril to their other resources and business. The amount of capital needed for modern business could hardly have been assembled and combined in any other way [emphasis added].4

The treatise goes on to say that the important elements of the corporate form are the right to hold property and otherwise deal with third parties as a separate person, limited liability for shareholders, continued existence when a shareholder dies or transfers shares, and centralized management and organization.

While this may all seem quite intuitive to a reader who has spent her entire existence in a society where transactions with artificial persons is routine, these corporate characteristics were quite disruptive. Without them, every enterprise that required the equity capital of more than one person would be subject to complex contracting issues, legal uncertainties, and financial risks that would make it extremely difficult to aggregate large amounts of financial capital. One leading English academic has noted the remarkable historical importance of the corporation:

That the corporation can explain the growth of nations around the world and the failure of others to progress is indicative of its macroeconomic significance. That the different nature of the corporation is associated with social benefits and ills and its changes over time with their emergence and eradication suggests that it is to the corporation that we should turn for the source of both our prosperity and our impoverishment.5

THE HISTORY OF THE CORPORATION

A very brief history of the corporation will help to explain why the development of the benefit corporation may be the leading edge of a critical turning point in economic history. Initially, when individuals wanted to engage in business enterprises, they could do so as individuals or, perhaps, as partners, but as such, they were subject to liability for everything that the enterprise did, and, whenever a partner left or a new partner was brought in, new contracts had to be established. This system did not work well for encouraging private enterprise that required large amounts of capital, but in the preindustrial age there was limited need for such capital formation.

Nevertheless, certain business enterprises did require significant financial capital. For example, trading companies required large amounts of risk capital to finance expensive operations abroad. Early English corporations were formed by royal act, creating charters for particular corporations to trade, such as the East India Company.6 In Anglo-American history, these were followed by legislatively created charters that enabled corporations to collect sufficient capital to fuel the investments that brought about the industrial revolution.7 Essentially, legislatures were choosing enterprises that they believed needed capital to deliver needed improvements—canals, bridges, railways, banks, and utilities. The enterprises were granted the advantages that came with incorporation. In exchange for these privileges, shareholders committed capital to enterprises that created social good.

Eventually, legislatures came to see the power of corporations to steer capital to productive use as an important public good, without regard to any particular industry. As a result, general incorporation laws were created, allowing any business to be structured as a corporation, without obtaining a charter from the legislature. This also had the salutary effect of depoliticizing incorporation, as access to the legislature was not a prerequisite to forming a corporation.

In 1811, New York became the first state in the United States to establish a general corporation law, but even that statute limited its use to corporations that manufactured textiles, glass, metals, or paint. Not until 1837 did a state adopt a general incorporation statute that could be used for any “lawful, specified purposes.” Within these statutes, states initially imposed limits on corporate power, requiring strict statements of purpose, and limiting the right to own other corporations, but eventually these restrictions were lifted, due in part to competition among the states for charters.8 As corporations grew in size and strength, they became the dominant players in the economy, and incorporation had fully shifted from a privilege to a right.9 At the same time, the corporation shifted from being a public institution to a private one.10 As a result, incorporation ceased to be viewed as a “concession” from the state.11

Corporations thus evolved as an institution created by government in order to benefit the societies they governed. They allowed investors to aggregate resources into an artificial person, without fear of personal liability. This, in turn, allowed for massive, efficient investment vehicles that create the goods and services that benefit society. As the economy became more complex, there were more instances in which these vehicles were advantageous. The end point of this evolution was general incorporation laws, which allowed any business to use the corporate form, without regard to social benefit.

The Investment Chain

THE STRUCTURE OF THE INVESTMENT CHAIN

The previous section discussed the history of the corporate form and touched on the rationale for granting it special rights. Corporate forms now dominate global business, with $70 trillion in equity capital invested in public companies, and more in private entities with corporate characteristics.12 This section examines the context in which that equity is purchased and managed.

The history of the equity investor parallels the history of the corporation itself in many ways. As the economy grew beyond one based on land and agriculture, individuals who accumulated wealth needed ways to invest that wealth in new businesses beyond land ownership—first trade, then industry, and eventually all forms of business activity. Corporate shares provided a method to do this. Investors were able to save, but also to access their wealth by selling their shares. Moreover, they could invest in many different enterprises, without having to take on any of the burdens of managing the enterprises. Shares in corporations provided limited liability, liquidity, and diversification. Investors could fund an enterprise without concern that they could lose more than they invested. Shares of stock in business became a way to save, accumulate, and transfer wealth.

But although savings through stock ownership originated as direct ownership by individuals, the global capital system has become a vast and complex network. For example, in the United States, the value of publicly traded stocks in early 2017 was more than $25.6 trillion, much of which is held by “institutional owners.”13 These institutions include banks, mutual funds, pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, insurance companies, endowments, and foundations.14 All of these institutions are holding that money on behalf of beneficiaries—insureds, pension beneficiaries, citizens, students, and others. Anne Tucker has pointed out that citizens’ participation in the stock market through this system is not voluntary; in the United States, in particular, workers saving for retirement are forced to become “citizen shareholders.”15 Those institutions employ asset managers, who in turn employ consultants and additional managers.

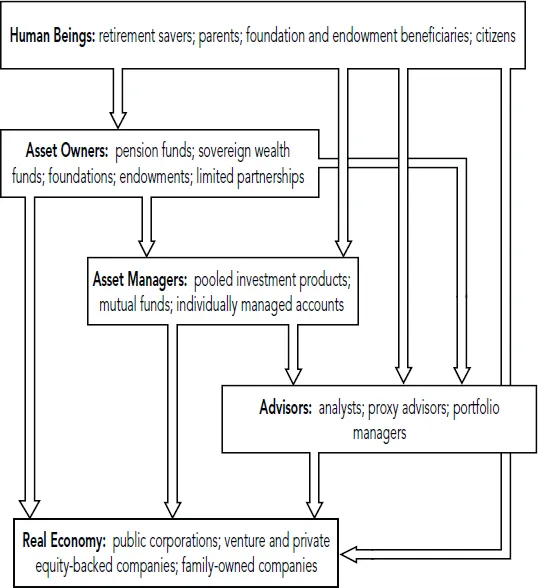

In this system, the directors and officers of corporations are essentially the last line of fiduciaries in a long chain. For example, an individual may buy a mutual fund in a 401(k) plan.16 That fund may employ asset managers, who in turn rely on outside consultants. Those consultants may recommend the purchase of shares in particular corporations, whose directors and officers finally deploy the assets that underlie the individual’s retirement savings into the real economy. As table 1 (on page 14) shows, assets may go through every link in the chain, or skip one or more links, as when a human being invests directly in a public corporation, skipping the layers of asset owners and managers. In contrast, a human being’s capital may flow through multiple links, encountering advisers at each level, and perhaps flowing through multiple layers of subadvisers.

TABLE 1: THE INVESTING CHAIN

One author described this as a long chain of delegation in the investment management industry:

At the top of the investment management industry are the individual investors, those who invest in pension funds and mutual funds or invest through bank savings accounts or insurance contracts. Individual investors are delegating most of their investment decisions to these asset owners. Asset owners then delegate asset management to in-house managers or external funds. These asset managers then delegate the decision on how to allocate capital across productive projects to corporate executives. Corporate executives can thus be viewed as the bottom of the investment management industry.17

This chain of investment performs many important functions. It allows members of society to protect their savings throughout their own life cycle and to save for housing, for education, and for retirement. It allows society to channel savings into productive investments. Finally, and most importantly for the purposes of this book, this investment channel creates a mechanism whereby asset owners— or their representatives—can oversee and provide stewardship for those assets.18

THE ABSENCE OF SOCIETAL RESPONSIBILITIES IN THE INVESTMENT CHAIN

The allocation and use of these assets has tremendous effects on civic life and the environment—the corporate executives at the bottom of the investing chain m...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Introduction: A Corporate Lawyer’s Journey

- Part I: Shareholder Primacy and Its Discontents

- Part II: Governing for Stakeholders

- Part III: Other Paths

- Epilogue

- Appendix A: Model Benefit Corporation Legislation (with Explanatory Comments)

- Appendix B: Delaware General Corporation Law Subchapter XV

- Appendix C: Quick Guide to Becoming a Delaware PBC

- Appendix D: Public Benefit Corporation Charter Provisions

- Appendix E: Quick Guide to Appraisal for Public Benefit Corporations

- Appendix F: Rubric for Board Decision Making of a Delaware Public Benefit Corporation

- Appendix G: Stakeholder Governance Provisions for a Delaware LLC

- Notes

- Further Reading

- Index

- About the Author