![]()

Part I

The Hispanic Employee and American Demographics

For reasons that are not well understood, fertility rates among non-Hispanic women in countries spread across the northern hemisphere are dropping. From Italy to Russia to the United States, these demographic crises threaten the nature and character of various nation-states. Italy, for instance, has the lowest fertility rate in the world. The United Nations reports that fertility among Italian women dropped from 2.5 children per woman between 1960 and 1970, to 1.2 today. As a result, the population of Italy is expected to decline by 28%, from 57.3 million in 1995 to 41.2 million by 2050.1 The consequences for Italy are sweeping: “Venice is on course to become a city virtually without residents within the next 30 years, turning it into a sort of Disneyland—teeming with holidaymakers but devoid of inhabitants,” John Hooper reported in the London newspaper The Guardian. “The register of residents, tallied every 10 years, shows that the population of Venice proper has almost halved—from 121,000 to 62,000—since the great flood of 1966.”2

In Russia, the situation is not as grave, but it is still alarming. Russia’s population peaked in the early 1990s (at the time of the end of the Soviet Union) with about 148 million people in the country. Today, Russia’s population is approximately 143 million. The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that Russia’s population will decline from the current number to a mere 111 million by 2050, a loss of an additional 30 million people, and a decrease of more than 20%. Russia loses more than 700,000 people annually, roughly the equivalent of losing the population of San Francisco, California, every year. For Russian leaders, this demographic reality is unprecedented in scope. Russian leader Vladimir Putin has characterized this problem as “[t]he most acute problem of contemporary Russia. It is a crisis, insofar as the integrity and future of that nation-state is threatened.”3

This time, come tomorrow, there will be fewer Italians and Russians in the world than there are today.

In the United States there is a similar demographic phenomenon unfolding. “Non-Hispanic White women and Asian women 40 to 44 years old had fertility levels below the replacement level (1.8 and 1.7 births per woman, respectively),” the Census Bureau reported in August 2008. “The fertility of Black women aged 40 to 44 (2.0 births per woman) did not differ statistically from the natural replacement level.”4 The number of non-Hispanic whites in the United States will begin to decline, while the African American population will remain more or less unchanged, within a decade. It is the higher fertility rates among U.S. Latinos and Latin immigrants to the United States, in fact, that account for the population growth in the United States: “Hispanic women aged 40 to 44 had an average of 2.3 births and were the only group that exceeded the fertility level required for natural replacement of the U.S. population (about 2.1 births per woman),” the Census Bureau report continues.5 It is clear that U.S.-born Hispanics are the principal catalyst for internal population growth, and were Hispanics removed from the demographic equation, the United States would, like Italy and Russia at present, be confronting the specter of depopulation, beginning in 2020.6

![]()

Chapter 1

The Changed American Workforce

The demographic role of Hispanics becomes more apparent when one considers that immigrants from Latin America account for almost 60% of all legal immigrants. In addition, there are an estimated 10–12 million people in the United States who have entered, or remained, in the country in violation of existing immigration laws. Most of these illegal aliens are Latin American. That the majority of these individuals—legal and illegal immigrants alike—are actively employed further strengthens the importance of Latins in sustaining economic growth, and the role of Hispanics as members of the American workforce.

These facts represent a demographic sea change affecting the American workplace in unprecedented ways. It is important to recall that as recently at 1990, the Census Bureau believed that Hispanics would not overtake African Americans to become the nation’s largest minority until 2020. It occurred fully two decades sooner than experts estimated. When it happened, earlier this decade, it transformed the United States into the fastest-growing Spanish-speaking nation in the world, and it made front-page headlines around the world. “Hispanics have edged past blacks as the nation’s largest minority group, new figures released today by the Census Bureau showed. The Hispanic population in the United States is now roughly 37 million, while blacks number about 36.2 million,” Lynette Clemetson wrote in the nation’s newspaper of record, the New York Times, in January 2003, documenting the federal government’s official announcement of the seismic demographic shifts that defined the character of the United States in the first decade of the twenty-first century.1

Every year since then the Census Bureau, along with other federal agencies, has continued to document the structural changes in the American workforce, changes that herald the ascendance of Hispanics—and the Hispanic employee—in ways that a mere generation ago were unimaginable.

Consider a few tantalizing facts:

Hispanics are almost a decade younger (9.5 years) than the general population;

More than a third of Hispanics are younger than 18 years old;

Fertility rates of Hispanics are higher than the natural replacement level;

More than 34 million Mexicans have a legal claim of some kind to seek to emigrate to the United States, which will be discussed later in the chapter

2;

Hispanic women who attain graduate degrees earn 15% more than their non-Hispanic counterparts; and

In September 2008 the United States replaced Spain as the second-largest Spanish-speaking nation in the world; only Mexico has more Spanish speakers.

3These changes have not unfolded without comment. “It is a turning point in the nation’s history, a symbolic benchmark of some significance,” Roberto Suro, then-director of the Pew Hispanic Center, said of the emergence of Hispanics as the largest minority, displacing the historic position held by African Americans. “If you consider how much of this nation’s history is wrapped up in the interplay between black and white, this serves as an official announcement that we as Americans cannot think of race in that way any [longer].”4 Other voices have been raised in acknowledgement—and alarm. “The persistent inflow of Hispanic immigrants threatens to divide the United States into two peoples, two cultures, and two languages. Unlike past immigrant groups, Mexicans and other Hispanics have not assimilated into mainstream U.S. culture, forming instead their own political and linguistic enclaves—from Los Angeles to Miami— and rejecting the Anglo-Protestant values that built the American dream,” Samuel Huntington, of Harvard University, wrote in the pages of Foreign Affairs.5

These demographic changes are also of profound socioeconomic consequence, simply because, unlike other immigrant groups, Hispanics have reached a “tipping point,” economically mandating that Spanish be one of the languages of business, and through higher birth rates, fundamentally changing the character of American society in this century. It is not news, for instance, that, during the second half of the twentieth century, certain American metropolitan areas struggled to remain economically viable in the face of sustained population losses. Buffalo, Detroit, and Chicago are three cities that experienced sustained—and debilitating—population declines beginning in the late 1950s. Only one, Chicago, was able to reverse this trend, and is now in the throes of an urban relative revitalization that is the envy of the Midwest.

A closer examination of how Chicago achieved this turnaround is instructive: “After half a century of seeing its population dwindle as people abandoned the core of the city and moved to the suburbs, Chicago has finally rebounded,” Pam Belluck reported in March 2001, after the Census Bureau released data from the 2000 census. “For the first time since 1950, the city’s population grew, and by a larger number than demographers and historians had been expecting. . . . The growth is primarily the result of an influx of immigrants, especially Mexicans and other Hispanics. . . . The biggest change in Chicago’s population mosaic is the increase in Hispanics, up more than 200,000 from 1990. While partly the result of better counting efforts, demographers say there has been a rapid stream of Mexicans coming from Mexico and from other American cities, and a growing influx of immigrants from El Salvador, Guatemala, Colombia and other countries.”6

If only Buffalo were this fortunate, it might reverse its sustained decline.

What this means, however, is that there are more Hispanics than ever before, that they are younger than the general population, and they are entering the ranks of the employed in greater numbers. Non-Hispanic whites, whose numbers are declining, are also older, which means they are leaving the workforce: “Happy Retirement” parties are held, primarily, for non-Hispanic white and African American employees, while the “New Employee Orientation” programs administered by human resources professionals are generally geared for new Hispanic and Asian (Indian, Chinese, and Korean immigrants) employees, with a minority of new workers entering the workforce being non-Hispanic whites or African Americans.

In consequence, there is a continuous change in the character of American society: this time, come tomorrow, there will be fewer non-Hispanic employees in the American workforce than there are today, all other economic considerations notwithstanding.

The fact of this undeniable reality, too, has not unfolded without comment, and controversy. The debate over illegal immigration is as much about the failure of the federal government to control the borders as it is about the apprehension and fear that Americans sense as they witness, in the course of their routine workdays and their personal leisure, how communities across the country are changing. Hispanics are everywhere; Spanish is heard more often on the public stage of civic life.

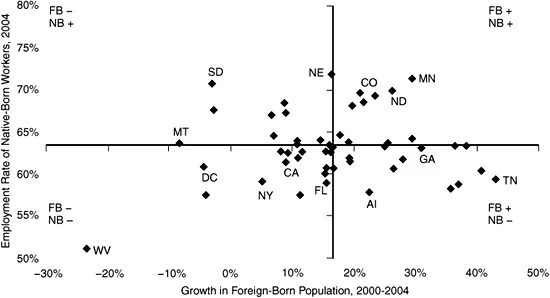

The impact of Latin immigrants on “Native Born”—U.S. Latinos included—cannot be characterized as either negative or positive. Their impact depends on a variety of factors, including the economic circumstances of individual states, specific industries, and the conditions of local labor markets. In the most comprehensive analysis available, the Pew Hispanic Center sought to analyze, state-by-state, the impact of all immigrants (Foreign Born workers) on the economic opportunities of American workers, including U.S.-born Latinos (Native Born workers). The results, when plotted on a matrix, demonstrate that there is no single answer to that complicated question.

To understand the overlapping and interrelated dynamics of these demographic changes, however, consider New Orleans. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, many residents decided not to return to that city, and as a result, the population remains just over half of what it was before the storm struck New Orleans. In the resulting absence of “Native Born” workers, industries—from construction to hospitality, restaurant to health services—have desperately sought to find employees, regardless of national origin, or even immigration status. Latin immigrants have filled that vacuum, swelling the ranks of that city’s workforce.

Growth in the Foreign-Born Population Is Not Related to Employment Rates of Native-Born Workers by State, 2000–2004

Center point is the average of growth in the foreign-born population and the average employment rates + denotes above average – denotes below average

“First came the storm. Then came the workers. Now comes the baby boom,” Eduardo Porter reported in December 2006. “‘Before the storm, only 2 percent [of babies born in New Orleans] were Hispanic; now about 96 percent are Hispanic,’ said Beth Perriloux, the head nurse in the department’s health unit in Metairie.”7 The reality that New Orleans is becoming a Hispanic city is undeniable. “The demographics of the health units used to be 85 percent African American, who had Medicaid, and 15 percent other,” Dr. Kevin Work told the reporter. “When the clinics reopened, I started seeing the faces changing. Now 85 to 90 percent are Hispanic undocumented, and only 10 to 15 percent have Medicaid.”8

How can one assess the “impact” of Latin immigrants on “Native Born” workers, when the former residents of New Orleans remain absent from their community? Can it be denied that New Orleans is fast-becoming a bilingual city, where the majority of “new” residents are native Spanish-speakers, and where Hispanic culture is changing the fundamental nature of that city’s social, cultural, and economic character? Of greater consequence, if eight or nine out of every ten children being born in New Orleans and neighboring communities is a Latino child, what will the city look like in the future? Has city government made plans for the fact that, beginning in 2010 and 2011, children enrolled in preschool and kindergarten are from households where Spanish is spoken at home, and...