eBook - ePub

Understanding Government Contract Source Selection

The 9 Behaviors of Great Problem Solvers

- 538 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Understanding Government Contract Source Selection

The 9 Behaviors of Great Problem Solvers

About this book

Your Go-to Resource for Government Contract Source Selection!

From planning to protest and all the steps in between, Understanding Government Contract Source Selection is the one reference all government acquisition professionals and contractors should keep close at hand. This valuable resource provides straightforward guidance to ensure you develop a firm foundation in government contract source selection.

Government acquisition professionals can reference this book for guidance on:

• Preparing the acquisition and source selection plans

• Drafting evaluation criteria and proposal preparation instructions

• Creating a scoring plan and rating method

• Drafting the RFP and SOW

• Conducting a pre-proposal conference

• Preparing to receive proposals and training evaluators

• Evaluating technical, management, and cost proposals

• Avoiding protest

Contractors can reference this book for guidance on:

• Selling to the federal government

• Reviewing a draft RFP and providing comments

• Participating in a pre-proposal conference

• Preparing a proposal that complies with RFP requirements

• Developing a strategy for teaming agreements, subcontracts, and key personnel

• Negotiating a contract

• Getting the most out of post-award debriefings

• Filing a protest

PLUS! Understanding Government Contract Source Selection provides a source selection glossary, an extensive case study, and sample proposal preparation instructions in the appendices to help you navigate the federal competitive source selection process. This complete guide is an indispensable resource for anyone striving to build their knowledge of government contract source selection!

From planning to protest and all the steps in between, Understanding Government Contract Source Selection is the one reference all government acquisition professionals and contractors should keep close at hand. This valuable resource provides straightforward guidance to ensure you develop a firm foundation in government contract source selection.

Government acquisition professionals can reference this book for guidance on:

• Preparing the acquisition and source selection plans

• Drafting evaluation criteria and proposal preparation instructions

• Creating a scoring plan and rating method

• Drafting the RFP and SOW

• Conducting a pre-proposal conference

• Preparing to receive proposals and training evaluators

• Evaluating technical, management, and cost proposals

• Avoiding protest

Contractors can reference this book for guidance on:

• Selling to the federal government

• Reviewing a draft RFP and providing comments

• Participating in a pre-proposal conference

• Preparing a proposal that complies with RFP requirements

• Developing a strategy for teaming agreements, subcontracts, and key personnel

• Negotiating a contract

• Getting the most out of post-award debriefings

• Filing a protest

PLUS! Understanding Government Contract Source Selection provides a source selection glossary, an extensive case study, and sample proposal preparation instructions in the appendices to help you navigate the federal competitive source selection process. This complete guide is an indispensable resource for anyone striving to build their knowledge of government contract source selection!

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

The Legislative History of Source Selection

Many people ask “Why do we have to do this?” during their first competitive source selection. Often, certain procedures are required by law. This chapter explains significant pieces of legislation, and the resulting regulatory framework, that affect competitive negotiated source selections. Occasionally, requirements appear not to make sense or seem overly burdensome, but each step of the acquisition process is backed by some law or regulatory interpretation. Laws and regulations drive this very formal, highly regulated method of spending public money.

Congress lays out the overall structure of and mandates for acquisitions in two primary statutes. The Armed Services Procurement Act of 1947 (10 USC 137) prescribes the general requirements for the Department of Defense (DoD), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and U.S. Coast Guard, while the Federal Property and Administrative Services Act (41 USC 251-260) covers almost all of the rest of the executive branch of the federal government.

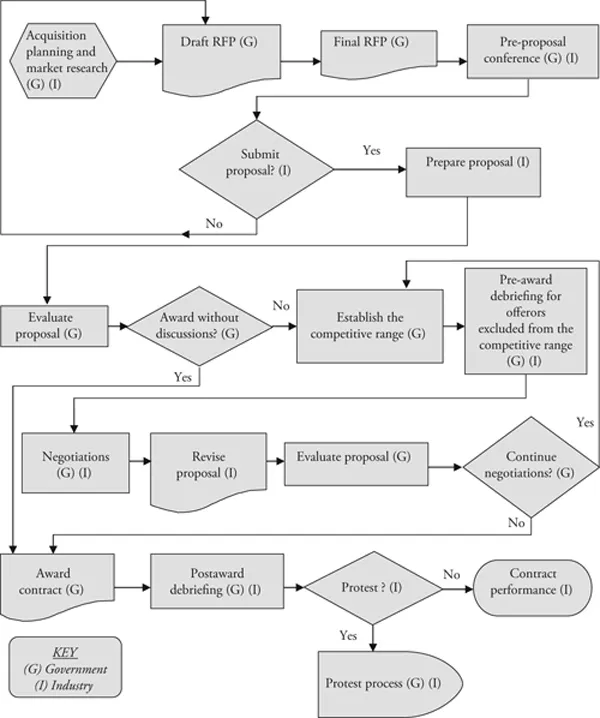

The process shown in Figure 1-1 illustrates the competitive source selection process. On this flow chart, Gs indicate the government’s responsibilities; the Is, actions taken by industry.

We will discuss the entire acquisition process, from strategy development through contract award. We will not discuss contract performance or closeout, which are important parts of the overall acquisition process but are beyond the scope of this text.

Every aspect of this process has been prescribed by Congress. When Congress perceives that there is a problem related to federal acquisitions, it is often very quick to impose a solution. This is one reason why the process seems extraordinarily complex—and in many respects it is. What must be remembered, however, is that the public is entitled to great visibility into how its tax dollars are spent, and further, it is entitled to a level of assurance that its money is spent in a fair, equitable, and unbiased manner. Hence the close scrutiny, disclosure, and formalization.

Figure 1-1 The Competitive Source Selection Process

Congress has passed many laws, called acts, that affect the way the federal government does business. Some of these acts resulted from studies that were intended to improve the acquisition process, such as the Federal Acquisition Streamlining Act (FASA) and the Federal Acquisition Reform Act. Others were passed in response to heavily publicized horror stories; the Competition in Contracting Act and the Procurement Integrity Act are two examples. In either case, congressional influence on the procurement process is significant.

Even if existing legislation already addresses a situation, Congress sometimes responds to federal acquisition problems by creating additional requirements for the process. The Truth in Negotiations Act and the Procurement Integrity Act are the result of Congress’ desire to fix a problem, even though it was already addressed by law or regulation. Let’s look at both of these acts and their impact on competitive source selection. We begin with the Truth in Negotiations Act (TINA), which became law in 1962.

THE TRUTH IN NEGOTIATIONS ACT

Many acquisition professionals think that TINA established the requirement for certified cost or pricing data, but this requirement was part of the old Armed Services Procurement Regulation (ASPR) clause number 3-807.3, Certificate of Current Cost or Pricing Data, from 1959. The clause required contractors to certify that the cost or pricing data they were submitting was current.

Regardless, the General Accounting Office (GAO) was concerned that contractors were continuing to overcharge the government, and in 1961 a clause (7-104.29) was added to the ASPR that permitted the government to reduce a contract price if a contractor provided defective cost or pricing data.

Congress passed TINA (Public Law 87-653) in September 1962 because it believed that the government was not receiving factual data from contractors and so was hindered in negotiations. This law is codified at 10 USC 2306 and was initially only applicable to the Department of Defense (DoD), the Coast Guard, and NASA, but Public Law 89-369 made TINA applicable to all executive branch departments and agencies.

Cost or Pricing Data

Cost or pricing data are information that prudent buyers and sellers would reasonably expect to have a significant effect on price negotiations and that are true as of the date of price agreement. The contracting officer (CO) and contractor may agree that the data can be accurate as of an earlier date that is as close as practicable to the date of price agreement.

It is important to note that cost or pricing data are factual, not judgmental, and as such, they must be verifiable. While they do not indicate the accuracy of the offeror’s judgment about estimated future costs or projections, they do include the data forming the basis for that judgment. Cost or pricing data are more than historical accounting data; they are all the facts that can be reasonably expected to contribute to the soundness of estimates of future costs and to the validity of determinations of costs already incurred. They also include such factors as:

- Vendor quotations

- Nonrecurring costs

- Information on changes in production methods and in production or purchasing volume

- Data supporting projections of business prospects and objectives and related operations costs

- Unit-cost trends, such as those associated with labor efficiency

- Make-or-buy decisions

- Estimated resources to attain business goals

- Information on management decisions that could have a significant bearing on costs.1

Submitting cost or pricing data can be a burdensome requirement, especially for large or complex acquisitions. For example, companies must certify that the data is accurate, in accordance with Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) 15.406-2. Contrary to what some government personnel assert, this information is not typically collected by all companies in the conduct of ordinary business. This is a unique federal government requirement. This is why companies look for exceptions to submitting cost or pricing data.

What exceptions to submitting certified cost or pricing data are available to contractors? Specifically, t he government may not ask for cost or pricing data for acquisitions at or below the simplified acquisition threshold. In addition, t he contracting officer shall not require a company to submit cost or pricing data to support any action (contracts, subcontracts, or modifications) when any of the following conditions apply:

- The contracting officer determines that prices agreed upon are based on adequate price competition. (Adequate price competition is discussed later in this chapter.)

- The contracting officer determines that prices agreed upon are based on prices set by law or regulation.

- The government is purchasing a commercial item , as defined in FAR 2.101, or any modification to the item, as defined in paragraph (3)(i) of that definition, that does not change the item from a commercial item to a noncommercial item.

- The head of the agency has granted a waiver.

- The action is a contract or subcontract modification for commercial items.

Even if one ofthese conditions does exist, however, certified data may still be required. For example, the U.S. Air Force KC-X aerial refueling tanker aircraft request for proposals required certified cost or pricing data even though it was a competitive acquisition.2 Sometimes, high-visibility or high-dollar-value acquisitions require certified cost or pricing data, although more recent changes have restricted contracting officers from automatically requesting certified data.

Adequate Price Competition

Adequate price competition exists when two or more responsible offerors, competing independently, submit priced offers that satisfy the government’s expressed requirements. The government will award a contract to the offeror whose proposal represents the best value when price is a substantial factor in source selection. To receive a contract award, the price of an otherwise successful offeror must be reasonable. If the price is found to be unreasonable, the determination of unreasonableness must be factually supported and approved at a level above the contracting officer.3

For example, the CO may be faced with an unusual situation where an urgent requirement must be awarded quickly and all of the offerors submitted price proposals that far exceed the government’s estimate. The CO could select the “lowest” price proposal but it still would exceed the government’s estimate. In this situation the CO must get approval to make the contract award in a timely manner to meet the urgent requirement.

Can there still be adequate price competition if only one offeror submits a proposal? In order for that to occur, the contracting officer must have a reasonable expectation, based on market research or other assessment, that two or more responsible offerors, competing independently, would submit priced offers in response to the solicitation’s requirements. In addition, the contracting officer must be able to reasonably conclude that the offer was submitted with the expectation of competition. Indications of expected competition include the following:

- The offeror believed that at least one other offeror was capable of submitting a meaningful offer, and had no reason to believe that other potential offerors did not intend to submit an offer.

- The contracting officer dete rmines that the proposed price is based on adequate price competition.

- The contracting officer’s price analysis clearly demonstrates that the proposed price is reasonable in comparison with current or recent prices for the same or similar items, adjusted to reflect changes in market conditions, economic conditions, quantities, or terms and conditions under contracts that resulted from adequate price competition.4

For example, the CO may determine after conducting market research that three companies are capable of meeting the requirements and send a request for proposals (RFP) to all three companies. One company is too busy to submit a proposal, and another company doesn’t want to enter the federal marketplace. So only one company submits a proposal, but it doesn’t know it submitted the only proposal. Thus, the CO may reasonably conclude that the company that submitted a proposal did so anticipating a competitive acquisition. If the proposed price is reasonable, the CO must get approval to award because only one company submitted a proposal.

The CO may, however, need information other than cost or pricing data to support a determination of price reasonableness or cost realism. A contracting officer should only requir...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- About the Author

- Dedications

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1: The Legislative History of Source Selection

- Part I: Getting Ready for Competition

- Chapter 2: Planning the Acquisition

- Chapter 3: Writing Evaluation Factors

- Chapter 4: Scoring Plans and Rating Systems

- Chapter 5: Writing the Rest of the Solicitation

- Part II: Preparing Proposals and Preparing for Evaluations

- Chapter 6: Conducting a Pre-Proposal Conference

- Chapter 7: Preparing the Proposal

- Chapter 8: Preparing for Proposal Evaluations

- Part III: Evaluating Proposals and Making the Award Decision

- Chapter 9: Evaluating Proposals

- Chapter 10: Awarding without Discussions

- Chapter 11: Establishing the Competitive Range

- Chapter 12: Discussions, Negotiations, and Proposal Revisions

- Chapter 13: Making Trade-Off Decisions

- Part IV: Completing the Source Selection Process

- Chapter 14: Conducting Debriefings

- Chapter 15: Filing and Responding to Protests

- Appendix I: Sample Proposal Preparation Instructions (Section L)

- Appendix II: Case Study: Boeing Tanker Protest

- Acronyms

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Understanding Government Contract Source Selection by Margaret G Rumbaugh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Commerce & Comptabilité & budgets. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.