3 1

Sold on Learning

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” Say, that’s not a bad way to start a book! Too bad Dickens beat us to it. The celebrated opening line from A Tale of Two Cities aptly describes the bittersweet world of training today.

This certainly could be the best of times for T&D. Executives see a widening gap between the skills and knowledge that businesses require versus those that the workforce can offer. “The need for skilled employees has never been keener,” declared a recent article in Fortune. “One-in-ten information technology jobs sits unfilled, and companies are almost as hungry for workers adept at so-called soft skills.”1

As a result, there is now virtual consensus among executives that learning must be a major factor in their ongoing strategies for business success. Even Wall Street, never a noted fan of T&D, has caught scent of this trend. “A tsunami of cash is poised over the [training] industry,” trumpets an article in Training & Development magazine. “Within two years, it will have reshaped everything.”2 Training Magazine reports, “The prevailing thesis on Wall Street is that knowledge workers will require more education and more training than ever before. As a result, corporate training budgets will increase substantially, which will mean more money flowing into the coffers of companies that sell training.”3

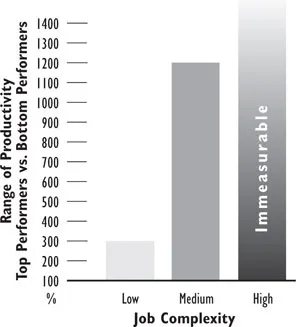

Investors who sense a link between growing demand for knowledge workers and increased demand for corporate education are definitely on to something. Research reported in the Journal of Applied Psychology showed that the productivity differential between top performers and low performers in a given job grows exponentially as job complexity increases (Figure 1-1).

The best worker flipping burgers in a McDonald’s, for example, might be as little as three times more productive than the worst, whereas the best performers doing skilled work on an auto assembly line (a job of medium complexity) might be 12 times more productive than certain others doing the same job. At the high end of the complexity scale, where knowledge workers such as investment bankers and engineers operate, the productivity differences between top performers and bottom performers reportedly grow so vast, they are virtually immeasurable.4

Figure 1-1: Productivity Range by Job Complexity

4 This means that in a knowledge-based economy, improving worker performance could yield unprecedented improvement in the overall productivity, competitiveness, and long-term performance of a business. That’s why so many of today’s business leaders are sold on learning.

Jack Welch is a prime example. “In the end,” says the Chief Executive Officer of General Electric, “the desire and ability of an organization to continuously learn from any source anywhere and rapidly convert this learning into action, is its ultimate competitive advantage.”5 More than a few executives now share this point of view—a circumstance that should make this “the best of times” for T&D. 5

Ends and Means

With such powerful trends combining to thrust learning into the spotlight, what could instead make these “the worst of times” for training?

Executives are keenly aware that training is but a means to learning. And while most business leaders are now sold on the idea that learning is crucial, some harbor serious doubts about whether the training in which they invest consistently yields learning that truly helps the business.

An attitude survey conducted in 1997 by U.K.-based Oxford Training, for example, asked line managers and their T&D counterparts in 65 major companies to react to 76 statements covering Training and Development services. A key finding of the study was summarized this way: “Line managers are significantly more reticent about the actual strategic impact of training than are training managers and professionals.”6

We’ve encountered plenty of anecdotal evidence to corroborate that finding. “Our CEO says, ‘When it’s all said and done, the one competitive advantage is the employee.’ And I can tell you, when he says that learning is vital, he means it,” says Denny McGurer, Vice President for T&D at Moore Corporation. “But for a lot of years, T&D had just about no credibility here. Management resented paying for it. They didn’t question the relevance of learning. They questioned the relevance of T&D.”

That distinction seems to be lost on some in T&D. Why else would the profession spend so much time touting the business value of learning, when it is the business value of training that executives have been known to question? Indeed, executives’ growing appetite for learning—combined with their doubts about the business value of training—is leading more than a few business leaders to look hard at their T&D investments.

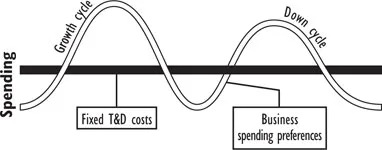

“Fixed” training costs—those that are embedded in the business—are likely to come under especially intense executive scrutiny because, these days, fixed costs might as well walk around wearing a “kick me” sign. Salaries and permanent training facilities are two examples of “fixed” T&D costs. They can’t be quickly dialed up and down by executives to fuel growth in times of opportunity or to protect profits when sales dip, as can the cost of vendors and other “variable” costs.

6 Figure 1-2: Fixed Costs vs. Spending Preferences

Executives are under relentless pressure to show strong earnings. So even when a business falters just slightly, fixed costs can look like a knife poised inches from the CEO’s heart. Many executives will then look to slash budgets for any and all items not directly linked to short-term revenue and profit generation. When they come to the line item for T&D, they may simply chop 20 percent or more off the top. That is often not a great decision, mind you, but what choice do they really have? No one has offered them data or analysis to demonstrate the business value training delivers. And there’s that earnings number to hit at the end of the quarter.…

Recessions have always been among “the worst of times” for training. But as the emerging knowledge economy raises expectations of T&D, executives’ patience with training of uncertain business value may be just as strained during periods of business growth. T&D should not expect to receive the benefit of the doubt. Rather, it should assume that executives will demand more unmistakable value in return for their training investments.

Comparisons to Information Technology

The recent past of Information Technology (IT) may offer some sound lessons for making the future “the best of times” for T&D. Consider these similarities between where IT was a decade or two ago and where T&D is today: 7

- Both are traditionally “backwater” functions thrust suddenly by the changing demands of business toward the top of executives’ strategic agendas.

- Neither function is very well understood by executives.

- Both are “big budget” items, made up largely of fixed costs.

- The economic impact of both is difficult to measure.

- Both functions are staffed (and often led) by people perceived to have plenty of “technical know-how” but a questionable grasp of business in general.

- Both operate as distinct subcultures within the larger business culture.

- Both are known to frustrate executives, who see practical business application lagging behind breakthroughs in available technology.

That last comparison may be the most significant. In the 1970s and 1980s, executives were excited about the potential of emerging computer and telecommunications technologies to serve their businesses. They were sold on the idea that IT, effectively applied, could drive business success. We can say with confidence, though, that many executives were impatient for IT to deliver clear efficiencies, new opportunities, and decisive competitive advantages to the business.

Successful IT organizations saw this. They didn’t waste much time trying to sell business executives on the potential of technology. Rather, they focused on making information technology more relevant, accessible, and practical for business application. Today, businesses use computers for everything from prospecting for customers to designing new products to keeping their books. Information Technology has automated repetitive tasks, dramatically speeded business operations, linked businesses electronically to their customers, opened vast new electronic marketing and distribution channels (like the Internet), and created lucrative new categories of products. 8

Such tangible contributions earned IT a place at the table where important business decisions are made. Most sizable companies now have a Chief Information Officer among their top executives. In sum, IT professionals made this “the best of times” for their field. And they did it by turning their technology’s potential into unmistakable value.

Top business leaders appear to be every bit as sold on learning today as they were sold on information technology two decades ago. And more than a few seem determined to make learning an equally explicit component of their business strategy. General Electric, Coca-Cola, Prudential, and other major corporations have appointed Chief Learning Officers. General Motors tapped the respected former president of its Saturn division, Richard “Skip” LeFauve, to lead its new General Motors University. And at PepsiCo, Vice Chairman Roger Enrico co-designed and now personally leads a leadership development program for up-and-coming PepsiCo executives.

Yet, as noted in Fortune not long ago, the Chief Learning Officer remains...