![]()

PART ONE

Leading Meetings

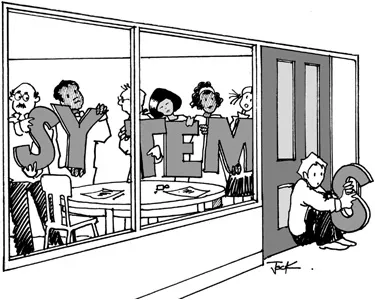

Get the Whole System in the Room

Control What You Can, Let Go What You Can’t

Explore the “Whole Elephant”

Let People Be Responsible

Find Common Ground

Master the Art of Subgrouping

These chapters present our views on how to plan, organize, structure, lead, manage, and facilitate meetings. Whether you assume responsibility for a meeting’s content, its agenda, its processes, and/or its results, you may find some useful tips and traps. We believe that most of our ideas are applicable whether you have formal authority or not.

Please notice that we use the generic term leading to cover all possible roles you might assume. Anytime you convene a group, or stand up in front and direct the proceedings, or take over briefly to make a presentation, or facilitate a conversation, you are leading, regardless of your relationship to the participants, position in the hierarchy, or role in society. You still have choices to make. These include

• whether you think the goal is reachable given the people in the room (Principle 1);

• figuring out what aspects you can influence and which ones you can’t (Principle 2);

• how to bring into the conversation all relevant information so that opinions can be formed, problems solved, or decisions made in a way that will satisfy the situation (Principle 3);

• the extent to which you are willing and able to share responsibility with others who also have a stake in what happens (Principle 4);

• whether or not finding common ground will be a useful precursor to future action (Principle 5); and

• how and when to pay attention to subgroups so as to keep people working on the task (Principle 6).

![]()

PRINCIPLE 1

Get the Whole Systemin the Room

At a meeting a few years back, we presented a case study of IKEA, the global furniture retailer, where 53 people had in 3 days decentralized a global system for product design, manufacture, and distribution (Weisbord & Janoff, 2005). The plan was developed by people from 10 countries and from all affected functions. Customers and suppliers participated, as did the CEO, who signed off on it immediately. The group formed implementation task forces on the spot. Two years later, the business area manager for seating reported that IKEA had transformed its product strategy and now routinely brought product developers, suppliers, and customers together early in the process.

At the end of our talk, one consultant, minimizing this significant achievement, called out, “Well, of course you were able to do all that in 3 days. Look who you had in the room!”

Well, she had a good point, and that is the theme of our first chapter.

Since Marv first proposed “the whole system in the room” as a key step for fast action in 21st-century organizations, this principle has influenced meetings all over the world (Weisbord, 1987, 2004). He derived this idea from studying his own consulting projects over many decades, noting the shortcomings of both expert and participative problem solving as the pace of change accelerated. Many methods that once worked now seemed to lag people’s growing aspirations for both systemic (rather than single-problem) solutions and for greater inclusion of people in using what they knew (in addition to expert input). Marv concluded that “getting everybody improving whole systems” was the great challenge for a new century. We needed to find methods enabling everybody to improve their own systems without having to become systems experts themselves. Experimenting with simple ways to do that, we and many others noticed that including all the relevant people in each meeting produced faster action on problems, decisions, policies, and plans than any other strategy. Moreover, this principle led to greater personal responsibility at all levels. If the participants didn’t act, they had only themselves to blame. Whatever meeting methods they used were secondary.

In this chapter, we give you a simple way to think about a “whole system” for any task and suggest how to match the people to the task. Our goal is to enlarge your thinking about what’s possible. We want you to consider the idea that no task is too complex if the right people can be brought in on it. This will be true for long meetings or short ones. There are literally thousands of meetings held each day in which people, lacking key participants, cannot use their skills, experience, or motivation. Your meetings need not be among them.

While writing this chapter, we asked several colleagues how they had used the whole system principle. The examples described here illustrate the many ways you can define a system and how inviting the right people can lead to extraordinary results.

SIX PRACTICES ESSENTIAL FOR IMPROVING WHOLE SYSTEMS

1. Define the “Whole System”

Define your system in relation to each meeting’s purpose. For any issue there will always be a core group supple mented by relevant others. We put “whole system” in quotes because you are unlikely to get every last person. Fortunately, you don’t have to. What you need are diverse people who among them have what it takes to act responsibly if they choose.

Think of the right mix as the people who “ARE IN” the room. (A friend pointed out this acronym to us years after we first wrote it on a flipchart, exactly in the sequence you see here! Who says there is no order in the universe?)

We define a whole system as a group that has within in it various people with

Authority to act (e.g., decision-making responsibility in an organization or community);

Resources, such as contacts, time, or money;

Expertise in the issues to be considered;

Information about the topic that no others have; and

Need to be involved because they will be affected by the outcome and can speak to the consequences.

When you define a system to make sure the right people “are in,” you enlarge its boundaries. You draw a bigger circle around your community, organization, or topic to include key people who may never have worked together. You offer every person a chance to discover the whole by creating a mosaic from what they already know. You make “systems thinking” experiential rather than conceptual. Indeed, the nature of the whole cannot be understood fully by anyone unless all participate. Nor can people be expected to act responsibly without understanding the impact of what they do. Having a “whole system” in the room opens doors no one has walked through before.

—EXAMPLE—

Influencing a Nation’s Conservation Policies

“When I worked in natural resources management for the Southern African Development Community, I arranged many workshops for senior conservation officials,” said Steve Johnson of Botswana’s Department of Wildlife and National Parks. “Most workshops were week-long and held in a site that represented a natural resources management topic under discussion. After running a number of these, we found that having just conservation officials meant preaching to the converted.

“So I changed course. I invited ministers, permanent secretaries, and directors from other ministries such as finance, commerce and industry, agriculture, tourism, and land affairs, the private sector, tribal chiefs, and other community members. Essentially we got ‘the whole system in the room.’ Suddenly we had action-to such a degree that a minister from Mozambique proposed a formal Community Based Natural Resources Management Policy in his parliament. The policy was developed the following year. He then asked for a similar workshop for his Mozambican Parliamentary Standing Committee—a cross-sectional group of parliamentarians-which led to one of the stronger natural resources processes in all of southern Africa.”

2. Match the People to the Task

No issue is too large or too small so long as the task is within the capability of those who attend.

—EXAMPLE—

Renewing a Day Care Center

A small district on the north shore of Oahu, Hawaii, involved diverse stakeholders in a planning meeting that would have major impact on local health care, highway safety, the high school curriculum, and many other matters. People became aware, for example, that the community had lost its only day care center for lack of funds, causing a crisis for 30 small children and their families. Two participants, a school cafeteria cook and a retired telephone lineman, inspired by their neighbors’ energy, decided to call their own meeting of parents, teachers, and concerned citizens. Within 3 months, after several more sessions, they found new funding and reopened the day care center. Nine years later they had expanded to three centers and were still holding “whole system in the room” meetings to solve problems.

The more far-reaching your objective, the greater your need for a broad selection of diverse players.

—EXAMPLE—

Reducing Gridlock in the Skies

In early 2004, the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) faced a terrible prospect: gridlock in the skies by summer unless users of the national airspace could agree on new procedures. For years experts had met to address increasing aerial congestion, only to end with conflict and indecision. This time FAA executives decided on an unprecedented meeting that would include all airspace users-airlines large and small, freight carriers, the military, business and private pilot groups, pilots’ and controllers’ unions, and others concerned with air traffic. Jaded by years of frustrating encounters, they rehashed stories of the system’s growing complexity.

Then a realization dawned on everyone. The relevant players were all present. If this group could not act, no one else would! Vowing at last to “share the pain,” they agreed to radical course corrections in the way air traffic is managed. Among other actions, they changed a decades-old norm of assigning airspace priority to aircraft, agreeing that the FAA, the only stakeholder with a systemwide view, would parcel out short delays to multiple flights across the country whenever necessary to minimize long delays at backed-up airports. With everyone present, it took just 18 hours to make badly needed system changes. (Weisbord & Janoff, 2006)

In the preceding example, all the decision makers and implementers shared the problem and its solution. Though they took on a momentous task, they had among them the capability to pull it off. Often, however, the task is too big for the people involved. Perhaps the most common planning error on planet Earth is convening groups to do tasks with key actors missing. This results in a well-known ritual widely reported in the newspapers. A position paper is written. A group of high-level authorities endorse a course of action. Experts agree on what’s best for everybody else. Many people assume that if big names or experts bless a plan, anyone who sees it will salute and start implementing. This happens so rarely it’s a wonder people waste time and money repeating such folly.

—EXAMPLE—

Experts + Money = 0

A state health agency known to one of our colleagues wished to establish a new policy for addressing teen alcohol and drug use in communities of color. They invited a task force of addiction experts (Expertise) and key funders (Resources) to study the issue. After deliberating for months, the task force proposed an excellent plan centered on school-based education and a peer-to-peer prevention model. It was promptly undermined by those who were not in the loop-community center service providers (Information), administrators and decision makers in education and substance abuse agencies (Authority), and teens and families (Need). None had been in the planning.

3. Match the Meeting’s Length to Its Agenda

Effective whole system meetings do not have to be 3 days in length. You can use short time frames when (a) the agenda is narrowly focused, (b) many others have already spent time working on key issues, and/or (c) the objective is noncontroversial but not well understood. In such cases, what you seek is shared agreement, the next steps people will take, and structures for moving forward.

—EXAMPLE—

Focusing Public Policy on Children’s Lives

The Maine Children’s Cabinet, five departmental commissioners chaired by the state’s first lady, in 2003 identified reducing Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) as a top state priority. Maine’s Department of Health and Human Services determined to use new research to influence state policymakers and stimulate community action on behalf of children and families. Richard Aronson, M.D., medical director of Maternal and Child Health, realizing that this ambitious goal required support from many agencies, organized two intense 2-hour meetings. Each involved a dozen key people who among them had what was needed to act but had never met all at once:

• academic experts from the University of New England;

• public health nurses;

• representatives of the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program;

• Child Abuse Action Network workers,

• members of the Child Death and Serious Injury Review Panel;

• State Department of Health and Human Services staff;

• State Department of Education personnel; and

• State Department of Corrections staff.

Sitting in a forum where all views could be heard, they advanced significantly the joint planning needed to translate research into public policy. The State Health and Human Services Department and the University of New England, for example, agreed to explore a community-based research partnership. The meetings also led to a presentation on the ACE research to the Children’s Cabinet itself, with the strong support of the first lady. Another outcome was a statewide forum on Adverse Childhood Experiences and Resiliency, resulting in action that will integrate research into clinical practice.

Aronson has run many such meetings from an hour to several days using whole system principles. Asked how he gets so many busy people together at once, he commented, “I’ve stopped using the word meeting because for so many people, it carries a negative connotation. Instead, I invite people to join a ‘dialogue,’ ‘action-oriented conversation,’ or ‘gathering.’”

4. Give People Time to Express Themselves

When the agenda directly affects many people’s lives and work, longer...