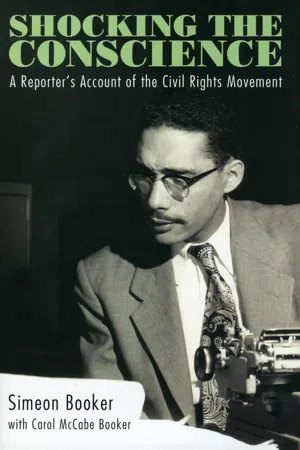

![]()

1

THE SLEEPING GIANT

Nothing in either my upbringing or training prepared me for what I encountered on my first trip to Mississippi in April 1955. I was a thirty-seven-year-old reporter for Ebony and Jet, two nationally circulated, black-owned magazines based in Chicago, and had worked previously on both Negro and white newspapers, including The Washington Post.

As a black man I had experienced the indignities of segregation in the border states of Maryland and Virginia, and even in the nation’s capital. “Whites only” water fountains, bathrooms, and lunch counters, job and housing discrimination, and unequal schools were not new to me. But Mississippi in 1955 was like nothing I had ever seen. What I witnessed there was not only raw hatred, but state condoned terror. I quickly learned that you could be whipped or even lynched for failing to get off the sidewalk when approaching a white person, for failing to say “Yes, sir” and “No, sir” to whites no matter how young they were, or for the unpardonable crime of attempting to register to vote.

Jet photographer David Jackson and I arrived in Memphis after an early morning flight from Chicago. The Tennessee port on the Mississippi River would be the “jumping off” point for most of our future trips into the Delta. In an area known as the “mid-South,” blacks considered the city a “turning point” in many ways, as suggested by the story of the black preacher from Chicago who was so scared on his first trip to the Deep South, he prayed, “Lord, please stay with me.” And the Lord answered, “I’ll stay with you, but only as far as Memphis!”

We had a contact at a car rental agency that rented to blacks, and would make sure we got a model so mundane and beat up it would never draw attention. Our destination was Mound Bayou, a small town in the Delta, that part of Mississippi that has been called the southern most place on Earth. That was one reason we were determined to get there before nightfall. We’d heard too many horror stories told and retold by the thousands of blacks who had fled North for us to take lightly our first venture into infamous territory. It wasn’t just poor economic conditions that made Mississippi Negroes flee. It was a culture we would never fully understand until we experienced it ourselves.

We were journalists, and although still somewhat naive about the Deep South, we were savvy enough to know that our profession alone might be sufficient to cause us trouble. So we did our best to look like locals, an effort I soon discovered was futile in any situation where it might really count.

It didn’t matter which of us took the wheel because Dave was every bit as cautious as I was, making sure we never exceeded the speed limit, or rolled through a stop sign. I was most comfortable trusting no one but myself, unless I was in an area where it was totally unsafe to get around without a savvy local, often a trusted contact, as a guide. But Dave, at thirty-three, with the skilled eye of a veteran photographer, was as adept as anybody at spotting trouble before it spotted us. He was also a pro at driving fast over back roads at night, even with headlights out when necessary to avoid detection.

In Chicago in those days, I used to wear a beret, but I knew it would be out of place in Mississippi, so I had stashed it along with an overcoat in a locker at Midway (still the Windy City’s primary airport in the mid-’50s). When we deplaned in Memphis, I also took off my suit jacket and bow tie and stuffed them into my duffel bag. (Most people wore their “good” clothes when traveling on airplanes in those days, and for a black man particularly, looking right and hoping to be treated with a modicum of respect meant wearing a jacket and tie.) The rest of my attire was a white, short-sleeve shirt, black pants, and scuffed-up shoes. On trips such as this, I would leave at home my portable typewriter with the Ebony logo emblazoned on the scratched-up case, and rely on a pocket-size notebook to record thoughts, interviews, facts, and details, waiting until I got back to Chicago to type the story. In later days, I would carry a Bible in plain sight on the front seat of the car, hoping to pass for a poor country preacher, but on this trip, we were still feeling our way. Like me, Dave was dressed in the style of a rural black man out to do no harm to the status quo. But even though he tried to “blend in,” his cameras were always a dead giveaway, and got him into trouble on more than one Dixie assignment.

The car had a radio, but it didn’t keep a station very long, so for the most part, we rode in silence, each wondering what lay ahead. Down the highway was our destination, the first scheduled voting rights rally in Mississippi since the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education (May 17, 1954) had sent shock waves across the nation. Nowhere was the shock felt more emphatically than in the Deep South, where politicians such as U.S. Senator James O. Eastland (D-Miss.), a plantation owner, were fiercely opposing the court’s ruling that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional.

In the early 1950s, segregated public schools were the norm in most of the United States, and were mandated in the entire former Confederacy. Although all the schools in a given district were supposed to be equal, black schools were far inferior to their white counterparts. I had a close look at the disgraceful neglect of black education while working at the Cleveland Call and Post, a black weekly, where I reported in-depth on that city’s shamefully neglected Negro schools, and won a national award for the series, the Wendell L. Willkie Award for Negro Journalism, sponsored by The Washington Post. Although the Supreme Court’s decision required only the desegregation of public schools, and not other public areas such as restaurants and restrooms, Southern whites were worried that it signaled a threat to all racial segregation—and white supremacy.

While other manifestations of the South’s Jim Crow system were bound to be mentioned, the primary focus of the rally we were about to cover was voting rights. Dave and I wondered whether there would be trouble, and specifically whether the local sheriff’s men would hassle people heading to the rally, even try to break it up. Or was the local white power structure so secure it would ignore the event and continue with business as usual? We doubted it, but we were outsiders; we just didn’t know.

Civil rights issues up to this time were argued in federal courts, mostly in litigation brought by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The bus boycotts, sit-ins, and mass marches came later. Voter registration drives were almost nonexistent except in this unlikely place, in the alluvial plain of the Mississippi Delta. The black town of Mound Bayou had hosted three in past years, but none since the Brown decision gave the state’s minority white population cause for alarm. (Blacks far outnumbered whites in Mississippi.) And so we drove toward a town that had long ago been dubbed “The Jewel of the Delta,” and wondered what really lay ahead.

One thing we knew was that there was nothing “antebellum” about the Delta. Framed by the Yazoo and Mississippi rivers, there wasn’t much happening in the area until after the Civil War. Virgin forests and fields covered almost the whole area in 1870. Twenty years later, railroad tracks opened up new markets for King Cotton, the South’s labor-intensive lifeblood. It was a life from which most of the blacks who’d fled North wanted to escape. The proliferation of tractors and other harvesting equipment in the 1940s left many of them little choice when the only work they’d had, as bad as it was, became insufficient to support their families. All along the highway, we could see evidence of the race-based system that kept white planters at the top and black workers, mainly sharecroppers, at the bottom. The shanties and rundown houses that lined the fields usually were not home to whites.

Outrageously racist sheriffs and judges rode roughshod over black people, wielding powers that became a brutal and intractable part of the system. Sometimes they left it to vigilantes to do the worst dirty work.

Despite this, or maybe because of it, a massive rally was scheduled in Mound Bayou on Friday, April 29, 1955. It was the state’s largest civil rights meeting in almost fifty years. Whatever happened, we knew it would make news for Jet’s national readership. We only hoped we’d live to file the story.

“THE JEWEL OF THE DELTA”

We were headed for Bolivar County, where Mound Bayou lies just off U.S. Highway 61, halfway between Memphis and Vicksburg. The town was established in 1887 by former slaves as a place where blacks might work for themselves instead of for whites, providing for each other everything they needed, and feeling safe, even while surrounded by the white feudal system. The local joke—although it was more true than funny—was that Mound Bayou was “a place where a black man could run FOR sheriff instead of FROM the sheriff.” From day one, Mound Bayou officialdom was black, from the mayor down to the cops. And although a dot on the map, with no more than 2,000 souls, the town had caught the attention of prominent Americans, including Booker T. Washington.

A renowned advocate of trade schools for blacks, and the founder of the Tuskegee Institute, Washington had impressed President Theodore Roosevelt, who invited him to the White House within weeks of taking office after President McKinley’s assassination. They got along so well, Roosevelt invited him back for dinner. The next day the South erupted in fury when the Associated Press (AP) reported it on the wire. Diehard segregationists took the presence of a Negro as a guest at the White House as an insult to the South, and particularly threatening to the self-respect of any Southern woman. It always seemed to come back to the Southern woman. A Southern white man was not going to stand for any black man being in close proximity to a white woman unless the black was a servant. If proximity couldn’t be avoided, it could never be on an equal basis.

According to historians, Roosevelt was disgusted by the outrageous attacks in the Southern press.1 So, a few years later, he gave them some payback. On a bear hunting trip at the mouth of the Mississippi River after the 1904 elections, he had the train stop in Mound Bayou where he very pointedly crowned the black township, “the Jewel of the Delta.”

Our contact person, and Mound Bayou’s most prominent citizen, was Dr. T. R. M. Howard, a tall, broad-shouldered, bear of a man who was a gentleman planter, businessman, and home builder as well as a physician. (The “T. R.,” coincidentally, was for Theodore Roosevelt and the “M” for Mason, which he added to his name out of appreciation for the white doctor, Will Mason, who had helped him acquire his medical education.) Born in Kentucky and educated in Nebraska and California, Doc Howard had begun his medical practice in Mississippi in the mid-’40s. By 1955, his civic activities (or more specifically, his civil rights activities) were having as much impact in the Delta as his medical practice, in which he performed as many as twelve operations a day and supervised a hospital where nearly 50,000 men, women, and children, most of them poor sharecroppers, could get treatment each year. After dark, however, his was a different world, in which he was warned repeatedly of a likely ambush if he ventured into the backwoods for nighttime speaking engagements. In the wake of Brown v. Board of Education, Mississippi was becoming even more inhospitable to anyone thought to be awakening “the sleeping Negro.” And that was exactly what Dr. Howard was trying to do.

Among his non-medical activities, he was president of the Regional Council of Negro Leadership (the “Leadership Council”), an organization pledged “to guide our people in their civic responsibilities regarding education, registration and voting, law enforcement, tax-paying, the preservation of property, the value of saving and in all things which will make the black community stable.”

The Leadership Council maintained that the poor schools attended by black children were what was driving their parents to pack up and head North. All the Council had been pushing for was parity—schools for black kids that were on a par with the ones white kids attended. Black kids, on average, attended school only four months a year, and spent the other months in the cotton fields, planting, hoeing, and picking to supplement their families’ income. Putting the kids into the fields to help their parents was the only way these poor black families could make enough to survive. When they did go to school, the kids often walked for miles while busloads of white kids sped past them to better schools with better-trained teachers, and superior equipment, books, and supplies.

Dr. Howard’s strategy for rousing and organizing the “grassroots” was to draw on the skills of blacks who had “made it” into leadership roles either in the business world, a profession, or the church. Working with the NAACP, the Leadership Council promoted civil rights, self-help, and business ownership. It made the white power structure nervous.

“Doc,” as we called him, was expecting us, and put us up in a modest, two-unit guesthouse he owned across the road from his own home. It was considerably more comfortable than many of the accommodations we would find in the future, especially when reporting on lynchings. On those assignments, we would get a black undertaker to sneak us into the funeral home after dark so we could photograph the body and get an account of the murder. Sometimes we’d spend the night and slip out before dawn. Most blacks in the vicinity would be too frightened to be seen with us.

This rally would be the first to be covered by a national news outlet, because even though the previous years’ rallies had each attracted around 10,000 participants, no one outside of Mississippi had taken any notice. This time, news of the rally would reach far beyond Mississippi. Chicago publishing pioneer John H. Johnson’s Jet magazine, launched in 1951, was already a staple in black households and businesses nationwide, and every week, Johnson was fulfilling his promise to bring its readers “complete news coverage on happenings among Negroes all over the U.S.”

Doc also had reason to believe that local reaction to this rally was likely to be different this year, because of the Brown decision. From the time the case was argued before the Supreme Court, and continuing ten-fold in the year since the decision had come down, racist tracts and pamphlets were being disseminated throughout the South, calling the school case Communist-inspired and supported. Meeting with us at his home the morning after we arrived, Doc handed me a yellow, five-by-seven-inch envelope, bearing an illegible postmark over four cents in cancelled stamps. It was addressed to:

T. R. M. Howard, negro

Mound Bayou, Miss.

Opening the metal clasp on the flap and removing the contents, I asked him who had sent them. Doc shook his head. “I have no idea,” he shrugged, “but I don’t think it was a friend.”

There was no note inside, just a handful of documents, including two crude booklets on construction paper, three racist pamphlets, and a copy of an editorial, “NEW JERSEY NEGRO EDITOR WARNS HIS RACE OF THE DANGERS OF INTEGRATED SCHOOLS IN THE SOUTH,” by Davis Lee, publisher and editor of the Newark Telegram. Lee’s controversial argument was that if schools were desegregated, blacks would lose out in every way to whites, including, most significantly, the loss of teaching positions and income. Lee’s preference was for “separate but equal.” The problem was that in reality, despite the handful of examples of black success that he cited, separate was never equal and never would be. Lee’s editorial had inspired a slew of racist tracts, some claiming to reflect the sentiments of other Negroes, arguing for maintaining the status quo. Mississippi’s White Citizens’ Councils had actually retained Lee to map a pro-segregation drive among the state’s blacks,2 but it was not clear whether he had any input into the two most creative, as well as particularly offensive, articles in the envelope which, using poor grammar and spelling and what was intended to look like Negro dialect, argued against desegregation. One was titled, “Mammy Liza’s Appeal to Her People (On the Question of Integration in Southern Schools),” while the other was characterized as a “sequel,” under the title “Uncle Ned Warns His People of the Dangers of Integration in Southern Schools.” Both reduced Lee’s arguments to minstrel-show perversions, as in the final couplet of Uncle Ned’s five-page “verse:”

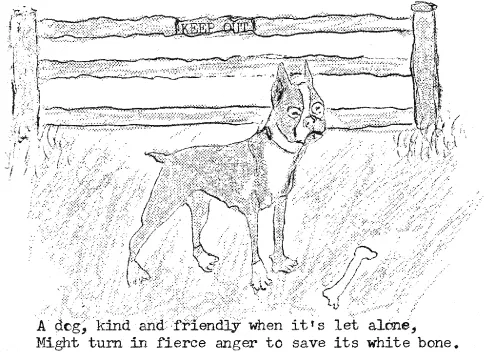

Racist tracts, some containing cartoons such as this, warning Southern blacks of the dangers of desegregation and outsiders of the consequences of meddling in the South’s affairs, proliferated throughout Dixie after the Supreme Court’s school desegregation decision.

De angels in heaben each has deir own level.

Stay in yo’ place … quit flirtin’ wid de devil.

“Take a look at the back page, too,” Doc suggested, pointing out that the booklet contained some not-so-subtle threats, as well.

Turning the pages, I found a cartoon depicting a fenced yard in which a bulldog stood warily eyeing his bone near a sign that warned “Keep Out.” The caption explained, “A dog, kind and friendly when it’s let alone, might turn in fierce anger to save its white bone.” In case that was too subtle, Doc noted the booklet’s opening lines:

Years ago, when ole Marse had a matter to settle,

Outsiders knowed well dat dey’d better not meddle.

It wasn’t too subtle for Dave and me.

One of the formal pamphlets in the envelope was called “Research Bulletin No. 1,” published in March 1954 under the title, “Negroes Menaced by Red Plot,” by a group calling itself the Citizens Grass Roots Crusade of South Carolina. The objectives of the Communists in the South, according to the pamphlet, were to get the vote for Negroes, and then round them up under the “Red banner of the Socialist Planners.” The group’s Research Bulletin No. 2, issued in October, several months after the Brown decision, similarly purported to tell the “Truth About the Supreme Court’s Segregation Ruling,” setting the tone for the tract with a quote from FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover in an address to the Daughters of the American Revolution on April 22, 1954:

To me, one of the most unbelievable and unexplainable phenomena in the fight on Communism is the manner in which otherwise respectable, seemingly intelligent persons, perhaps unknowingly, aid the Communist cause more effectively than the Communists themselves.

The pamphlet made good use of that quote to link any and all support for Negroes to a Red plot.

Although some blacks in Mississippi were either duped by this propaganda or too scared to do anything but continue with life ...