![]()

PART I

The Politics of Safety and Justice

![]()

1

The Coupling and Decoupling of Safety and Crime Control

An Anti-Violence Movement Timeline

MIMI E. KIM

Introduction

Over the past four decades, the U.S. feminist anti-violence movement addressing domestic violence, sexual assault, and, more recently, stalking and sex trafficking has developed a strong crime control approach. In response, the term “carceral feminism” was coined to describe the close collaboration between feminist social movements and the carceral arm of the state.1 Critical feminist and legal scholarship now solidly locates the anti-violence movement at the forefront of liberal contributions to the construction of the conditions of “mass incarceration.”2

By the passage of the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) as part of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act (Crime Bill) of 1994, feminist social movement leaders who helped to craft and support this legislation remained remarkably unaware of the troubling implications of tethering social movement success to the passage of what is now recognized as a draconian crime bill.3 However, rising and widespread public concern over mass incarceration, mounting critique aimed at feminist complicity with pro-criminalization policies, and internal social movement turmoil over the consequences of its investments in crime control have resulted in significant fissures in the anti-violence movement’s pro-criminalization stance. What developed into an unquestioned bulwark of the U.S. feminist anti-violence position has weakened under a confluence of forces that can no longer uphold glib acceptance of crime control as the primary response to gender-based violence.

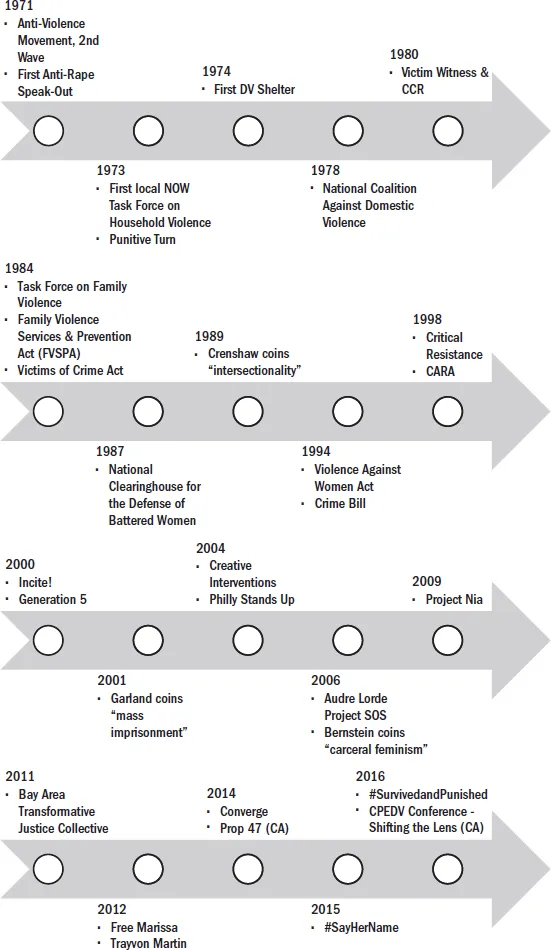

The selected social movement timeline in Figure 1.1 juxtaposes key events, policies, and organizational innovations within the anti-domestic violence movement (top of the timeline) with policy developments more closely associated with the evolving carceral state (bottom of the timeline). The timeline spans the period from the 1970s to the present, beginning with the formation of the anti-rape movement in 1971 and the anti-domestic violence movement in 1973,4 the latter date coincidentally marking the start of the “punitive turn” and the five-fold rise in U.S. rates of incarceration that would characterize the next four decades.5 While it is by no means a comprehensive timeline and fails to capture important historical factors that long pre-date the 1970s, the chronology of events reveals insights into the construction and possible dismantling of what we now know as carceral feminism. This chapter traces the evolution of the mainstream feminist anti-violence movement in its relationship to criminalization, the development of an alternative or counter-hegemonic anti-carceral feminist movement, and the intersection between these two movement forces.6 The narrative that follows refers to events featured on the timeline and expands upon and elucidates some of the contextual factors that contribute to and result from key historical moments.

Figure 1.1. Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Dep’t of Justice, Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics 500 tbl. 6.28 (Ann L. Pastore and Kathleen Maguire, eds., 2003); E. Ann Carson and William J. Sabol, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Prisoners in 2011, at 6 tbl. 6 (2012); E. Ann Carson and Daniela Golinelli, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Prisoners in 2012–Advance Counts (2013).

The Anti-Domestic Violence Movement: Formative Years

Early 1970s: Second Wave Beginnings

The feminist anti-violence movement emerged in the early 1970s, a relative latecomer in a second-wave women’s movement that was already in full force in the 1960s.7 Violence against women emerged as a social problem with the first anti-rape speak-out by a radical feminist group, the Redstockings, in New York City in 1971 and attention to the plight of “household violence” through the formation of a local NOW Task Force on Household Violence in Pennsylvania in 1973.8 The next year, the first explicitly feminist and organized battered women’s shelter began with Women’s Advocates in St. Paul after a small group of feminists who had begun a legal crisis line became alarmed by the number of women seeking help for violence suffered at the hands of husbands and boyfriends.9

Notably, 1973 also marks the punitive turn in the United States, beginning a dramatic upward rise in rates of incarceration that had remained relatively unchanged for the previous fifty years, from the time when such statistics were first recorded.10 During the formative years of the anti-domestic violence movement and the carceral build-up, relationships between early shelters and advocacy programs and law enforcement were non-existent, or uneven at best. In the 1970s, law enforcement viewed family violence as a private matter, outside the purview of the law even in the case of physical assault. However, some local programs experienced more sanguine relationships, often based upon personal relationships with a sympathetic police chief or individual law enforcement officer.11 By the late 1970s, feminist-led litigation against local police departments for “failure to protect” began to pressure policy changes, signaling shifts in police procedure in the case of domestic violence, and to be used to leverage other social movement demands to take violence against women seriously.12

Late 1970s: Early Federal Intervention in Domestic Violence

While feminist anti-violence advocates were demanding law enforcement changes on the local level, feminist-identified proponents serving in Congress and populating White House staff positions under the Carter administration began to permeate the federal agenda.13 The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence (NCADV), the first national organization representing battered women and the anti-domestic violence movement, formed in 1978 by newly identified anti-domestic violence leaders and activists and gathered at a national consultation sponsored by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, “Battered Women: A Public Policy.”14

Around this same time, the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA), a former branch of the Department of Justice established under Nixon and continued under Carter, identified the emerging issue of violence against women as one deserving federal attention and resources. With this unprecedented federal attention to violence against women, an issue only gaining feminist attention, some social movement activists warily greeted the advent of Department of Justice funding with the warning that “federal funds have coopted the grassroots, community-based women’s groups that initially brought the problem [of violence against women] to the attention of the public.”15 Department of Justice money, in particular, was suspect as the “blood-tinged” nature of law enforcement, and the use of LEAA funding guidelines was seen as a way “to control and subvert battered women’s movement to their own interests.”16

That early caution, published in 1977 in the first collective newsletter of the battered women’s movement, the National Communication Network Newsletter, reflected the radical racial justice, welfare rights, and anti-war social movement antecedents to the rather late-blooming anti-rape and battered women’s movements that emerged in the United States around 1971 and 1973, respectively. However, the opportunity to develop early innovative sexual assault and domestic violence programs under the auspices of a $3 million LEAA initiative that began and ended with the Carter administration proved to be sufficiently compelling, enough so that such warnings were taken as a challenge or were simply dismissed.

Early 1980s: The Emergence of New Carceral Actors and Organizations

Some early feminist leaders sought a more systematic challenge to law enforcement impunity in situations of domestic violence, crafting innovative organizational formations leading to rapidly replicable forms17 that would go on to significantly change the make-up or constitution of the anti-violence “social movement field.” The shift from a social movement almost devoid of law enforcement to one featuring close collaborations between feminist social movement institutions and the criminal justice system rapidly followed the establishment of new organizational forms initiated through social movement demands. The domestic violence-related Victim Witness program, begun in San Francisco in 1980, and the Community Coordinated Response, first developed in Duluth, Minnesota, in that same year, were key innovations crafted by feminist leaders that established formal collaborative relationships with law enforcement.

As a result of formal collaborative organizational forms and their replication, boundaries between social movement actors and institutions within civil society became blurred with those of law enforcement, thereby increasing vulnerability of the feminist social movement to the agenda and institutions of law enforcement. The rapid replication of these hybridized institutional spaces led to the increased occupation of the formerly autonomous feminist social movement with a new set of criminal justice actors and institutions, thereby contributing to the construction of a carceral feminist social movement.18

These collaborative initiatives with law enforcement also set into motion some of the enhanced crime control policies that contributed to the sweep of mandatory arrest laws that strengthened the coupling of social concerns about domestic violence with the strong arm of policing. In 1981, the Duluth Project proposed and initiated a mandatory arrest policy that caught the attention of feminist social movement actors, law enforcement officials, legislators, and a newly interested public.19 In 1984, the Minneapolis Experiment on Mandatory Arrest, carried out by the Minneapolis Police and criminological researchers, conducted a larger-scale experiment on the impact of mandatory arrest on domestic violence outcomes.20 Despite what would be revealed as inconclusive outcomes regarding the effectiveness and impact of mandatory arrest policies in further studies, the result of the Duluth Model and this first experiment catapulted a sweep of mandatory arrest laws through localities and states across the nation.21

Mid-1980s: The Reagan Crime Control Agenda and the Rise of Victim Rights

The Reagan era of the 1980s introduced an invigorated conservative ideology and policy agenda that accelerated the rhetoric of crime control and the reliance upon law enforcement as a foundation of a revised social contract and organization of governance. The first federal domestic violence bill, expected to be passed under th...