![]()

CHAPTER 1

Essae M. Culver Answers the Call, 1925

From the last decades of the nineteenth century until the dawn of World War II, American culture increasingly became “‘a culture of print,’ that is, a culture that was knit together and defined by the printed word.” As printed materials grew more diverse and more readily available, citizens relied upon them more and more to disseminate political, economic, and cultural information, “which circulated faster, more cheaply, and more widely than ever before” and contributed to the growing imperative to make books available to all the people through public libraries.1

Toward that goal, during a thirty-year period beginning in 1889, Andrew Carnegie, the Pittsburgh-based business tycoon who had made a fortune in the steel industry and focused his prolific philanthropy on libraries, contributed $41 million to construct 1,679 public library buildings. This program of beneficence continued after his death in 1919 under the auspices of the Carnegie Corporation of New York. During the next few years, however, Carnegie administrators grew increasingly disappointed that many municipalities had accepted funding to construct buildings but failed to move beyond bricks and mortar to engender meaningful library programs. Meanwhile, as the American Library Association (ALA) prepared to celebrate its semicentenary in 1925, the library profession’s leaders acknowledged gloomily that national library development had progressed with distressing sluggishness—a circumstance mirrored in Louisiana. Members of another organization, the League of Library Commissions, shared this concern. The League, a group of some twenty state library agencies that came together in 1904 to work toward improved library service, stood ready “to help any of the states which, for one reason or another, had done little or nothing to help themselves,” but its leaders hardly knew where to begin. “Little power or contact with those that were unconvinced” and lack of funds hampered both organizations.2

Shortly before the 1924/25 winter meetings in Chicago of the ALA and the League, news spread that the Carnegie Corporation “would entertain a proposal to put on a state demonstration in library service under the direction of the League. Before the Chicago conference adjourned, negotiations had gone far enough to make it fairly certain that $50,000 to be spent over a period of three years would be forthcoming for this purpose.” In his capacity as League president, California state librarian Milton J. Ferguson subsequently accepted Carnegie funding in that amount to promote library development.3

Ferguson headed a committee charged with implementing this project. It began by tackling the question of where to spend the Carnegie money and League effort. Members “soon decided that the best results could be expected from concentrated sowing in one state, rather than dropping a few seeds in hopeful abandon throughout the nation.” They sought a state deficient in library development, but one that presented a reasonable prospect for success and so positioned geographically that its achievements would constitute a model for its neighbors. Further, it should offer open-minded elected officials, at least a small group of influential and willing supporters, and a legal mechanism to perpetuate the League’s work at the end of three years. Because library progress had lagged more in the South than in any other region of the country, selection of a southern state seemed likely—and the committee had at least ten to choose from. Louisiana, known to be among the states most deficient in the quantity and efficacy of its libraries, appeared to offer fertile ground for their nurture—and for demonstrating to the citizens how a centralized library agency could facilitate that effort.4

On his way home to California from the ALA mid-winter meeting, Ferguson visited the Pelican State to assess for himself whether Louisianians commonly held a statewide resolve to cultivate their libraries using intensive modern methods. There he found the general library law of 1910, which had not been actuated because of lack of financial support, and the 1920 law that had created the yet-unfunded Louisiana Library Commission. More than 1 million people remained without access to library service. Some Louisianians, however, suspected ulterior motives. Governor Fuqua, for example, perhaps recalling post–Civil War American history textbooks from northern publishers that required schoolchildren to master regional trivia irrelevant elsewhere, mistrusted the plan “as a ‘Yankee scheme to educate the heathen of the South’” but, upon receiving assurance that “success of the kind we were looking for would require local appropriations, he declared himself open to conviction.” Fuqua agreed to appoint or reappoint the commission members under whose supervision the project would be carried out if Louisiana were selected.5

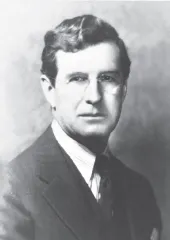

Milton J. Ferguson, ca. 1935, around the time he served as president of the American Library Association. (American Library Association Archives, 99/1/13, Box 2, Folder: Milton Ferguson, President, 1938–1939)

Ferguson considered Louisiana “attractive for several reasons: the people were enthusiastic and unbelievably hospitable, the ground was not encumbered by any structure which must be removed to make way for a newer edifice, and laws had been enacted so that money alone was needed to set the wheels in motion.” Though the obvious frontrunner, Louisiana was not without competition. News of this “project of making a library ‘demonstration’ in states backward in library development” spread quickly, “and, in the spreading, the sum grew like the paper profits on a bull market.” Thirteen states eagerly applied for consideration. Representatives of some of them, in addition to explaining why theirs merited selection, offered reasons why Louisiana should not be chosen. Meanwhile, local preparations were underway so that the state, if designated, would be ready. On March 9, 1925, Margaret Reed and Katherine Hill met with Governor Fuqua to discuss the prospect. While reserving the authority to use his own judgment, the governor asked them to submit a list of names of interested potential commissioners. Neither of the women wanted to continue in that capacity, but Ferguson had inferred that they would be expected to do so if Louisiana received the funding. They acquiesced, for they “felt that the sacrifice would be worth while if we can get this work started.”6

On March 20, the governor named new members to the Louisiana Library Commission: two New Orleanians, G. P. Wyckoff, professor of sociology at Tulane University, and Eleanor McMain, head of a settlement house called Kingsley House, as well as Forrest K. White of Lake Charles, superintendent of Calcasieu Parish schools. As expected, the governor reappointed Hill and Reed. Unlike most governors, who strove for geographic distribution when populating commissions such as this, Fuqua chose appointees from the same region of the state (the southern section). He reasoned that because roads everywhere were deficient, geographical proximity facilitated getting together.7

Ferguson returned to Louisiana in April to attend the first meeting of a newly reorganized and reinvigorated Louisiana Library Association (LLA) and, on behalf of the League of Library Commissions, offered the state a fund of $15,000 per year for three years “for the purpose of making a demonstration of modern library service in the south.” The commission accepted the grant and immediately voted to appoint as executive secretary “a librarian experienced in the best developments of Library Commission work.” A decision on the exact forms of work to be undertaken was deferred until a suitable librarian accepted the position and arrived to take up the work. The commission planned to collaborate, meanwhile, with the LLA to educate Louisianians regarding the value of the commission’s work and to organize local groups interested in founding libraries.8

Ferguson “had someone in mind for the job [of executive secretary], and there was never a rival candidate.” As he wrote to Wyckoff, “The success of the work in Louisiana or any place else will depend very largely upon the ability, the understanding, the tact, and the skill of the executive secretary. I have thought all along that a southern person would be best for this position. I have in mind, however, a librarian who has great understanding, who has a most pleasing personality, who has had great success in work with clubs of all kinds, and who in short is what one might call a ‘complete’ librarian, but she is not of southern extraction. She is not offensively of one section or of another.” Based on Ferguson’s recommendation, Wyckoff wrote the next day to Essae M. Culver, offering the position of secretary. “Please,” he implored, “do not decline the offer before consulting [Milton Ferguson] after his present visit to Louisiana.”9

“The Great Need of the Rural People”

Born in Emporia, Kansas, on November 15, 1882, Essae Martha Culver was the youngest of five daughters and three sons of Joseph Franklin Culver (1834–1899) and Mary Murphy Culver (1842–1920).10 Her unusual first name, which she fervently disliked, was pronounced like the word “essay” or the letters “S. A.” Her parents creatively named her after an uncle called Sam; the sound of her first name, when coupled with the initial letter of her middle name, spelled SAM.11

In later years, Essae Culver described a seemingly idyllic childhood in the embrace of a close-knit extended family that included grandparents and cousins as well as parents and siblings, giving her opportunities to become comfortable with people of all ages. “We lived in a large house on a hill called University Place,” she recalled. “The hill sloped down to a river and on the slope was an orchard, with apples, peaches, pears, plums, a vegetable garden and two grape arbors, and berries of every description. We had horses to ride and drive, dogs and cats to play with so that most of my time was spent out doors.” Her mother “always insisted if we started any project we must finish it if at all possible and no matter how discouraging the outlook.”12

Emporia had no public library when Essae was growing up, but the books that filled the Culver house stimulated her early interest in reading. The strongest influences in the youngster’s life “were religion, education, and music,” she reminisced. “Every member of the family either played an instrument or sang, and we were all given an opportunity to study. . . . My father said we could have all the education we could take but he would probably not leave us much in his will. He died before I was ready for college and there was never any question of my not going to college, for the whole family pitched in to see that I got a college education.”13

After her father’s death in 1899, Essae and her mother moved to Arizona. Relatives on the Murphy side of the family already resided there, as did two of the older Culver daughters, who had followed their parents into the teaching profession. Essae resolved to do anything else. She graduated from Phoenix Union High School in 1901 and went on to Pomona College in Claremont, California, where she majored in piano and voice; she was a mezzo soprano. Although she did not consider herself a proficient pianist, “her mother cherished dreams of a concert career for her.” The concert stage’s loss proved to be the library world’s gain, for Essae had decided, while employed as a student assistant in the college library, to make librarianship her career. Her brother Chester offered to pay her expenses to any library school in the country as a graduation gift, “so long,” he added, “as you don’t fly too high!” After receiving her degree in 1905, Essae worked for two years in the Pomona College library and for two weeks at the Detroit Public Library to see what public library work was like. Her sister Harriett predicted, “Being a librarian may be all right, but you’ll never set the world on fire at it.” Essae told her, “If I ever accomplish anything, it may very well be due to that remark!”14

Essae Martha Culver in 1903, at age twenty-one. (Special Collections, Honnold/Mudd Library of the Claremont Colleges)

Professional training for librarians was then in its infancy, and none existed yet in the West. Many prospective librarians from that area, especially those who, like Essae, held co...