![]()

John Hejduk

The studies of Loos and Rossi served to outline the formal and temporal qualities of lateness, yet these still leave the opening question of this essay partially unanswered: whether a study of lateness can serve to reevaluate the nature of the critical in architecture.

The Texas Houses

The mode of critique prevalent in the modern was one of dialectic opposition. This attitude was reflected in modernist notions of time—the new spirit championed by Le Corbusier and others marked a sharp line between the past and the present. The modern was the antithesis to neoclassicism’s thesis as well as to the theoretical framework of twentieth-century criticism, in particular at the apex of midcentury critical theory, where dialectics proved to be a dominant device. With the work of John Hejduk, it is possible for lateness to introduce a nondialectic condition into the language of architecture and into its modes of criticism. A comparison of Hejduk’s Texas Houses and Wall Houses can serve to establish this contrast between dialectical and nondialectical, for each corresponds to different temporalities in Hejduk’s work: modern and late. The seven Texas Houses are evidence of Hejduk’s desire to critically interrogate the modern, and each house challenges the basic tenets of modernist language in different ways. Yet, as a group, the houses keep modern notions of space intact, as shown through the following analysis of the column, the free plan, and the figure in three of the seven houses.

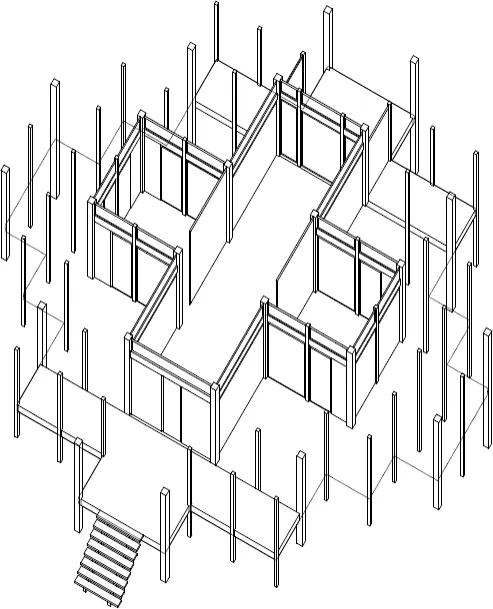

The column as an integer of an uninflected overall spatial grid is one of the central manifestations of the modern in architecture. There are two different column types, each of which suggests different spatial organizations that in turn define two dominant conceptual trends. These types are the square column, exemplified by the work of Mies van der Rohe, and the round column, as used by Le Corbusier. Square columns imply a gridded space, while round columns suggest a fluid space. The Texas Houses adopt the square column, and as such, Hejduk aligns himself with Mies, who, more than Le Corbusier, conceptualized modern space through the Cartesian grid. Furthermore, the square column differs from the round column since it marks both a point-grid and a grain. In other words, while the round column allows for the unimpeded flow of space around it, the square column begins the striation of space both parallel and perpendicular to a potential grain in the space. Hejduk’s Texas Houses take up the evocation of the square column grid, and as a result, the undifferentiated point-grid is constantly at play against both virtual and actual striations of space. In this way, the houses do not contest the logic of the modern, but rather use this disposition of the square column to engage in dialectical contrasts, questioning the language of modernism without denying it or transcending it.

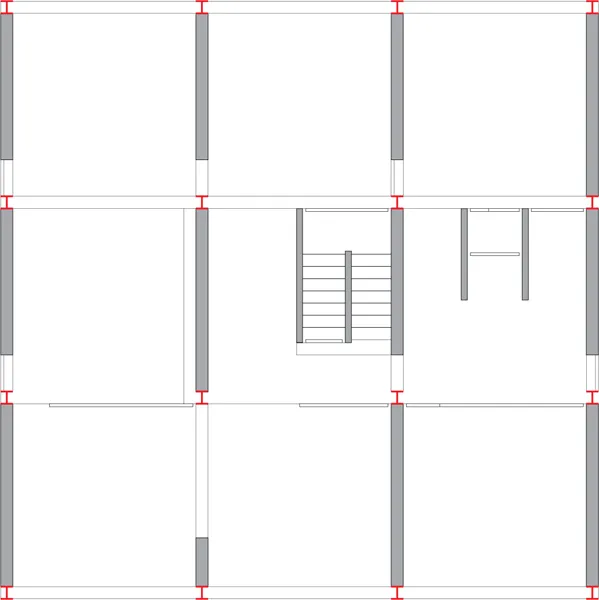

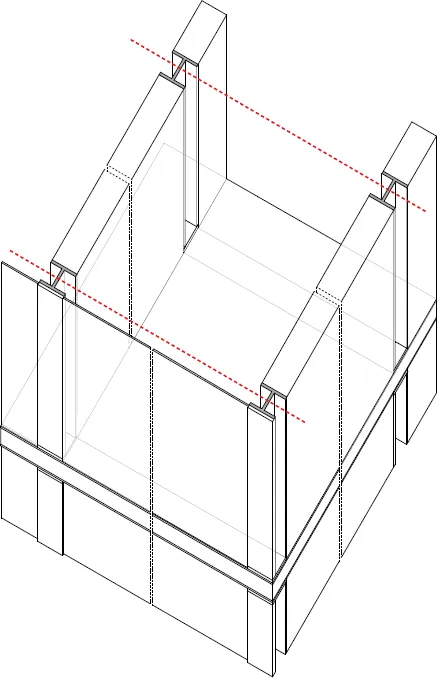

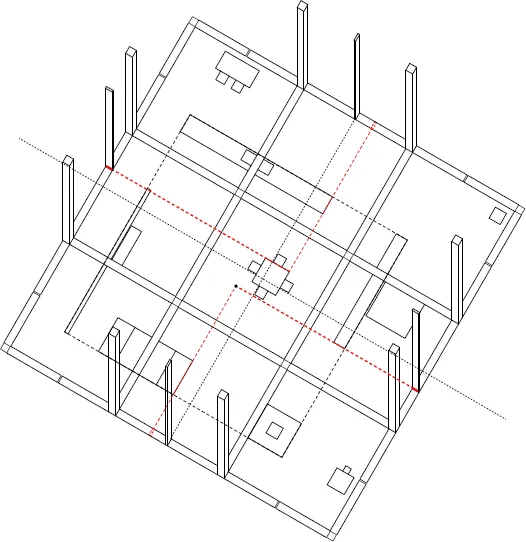

House 4 provides an initial example (figure 21). The plan has a nine-square organization, with all the walls in the project running in a single direction, giving the project both an abstract context and a definitive grain. Each intersection of the nine-square grid is marked by an I-beam, all of which are oriented in the same direction: the flanges run perpendicular to the wall, and the web is parallel (figure 22). The result is an explicit interruption in the continuity of the walls and the introduction of a contradictory grain in the opposite direction, due to the negative space that is formed between the facing I-beams (figure 23). The house, then, counter-poses solid and void within the context of the grid; the nine-square is not static, because it oscillates between two orientations.

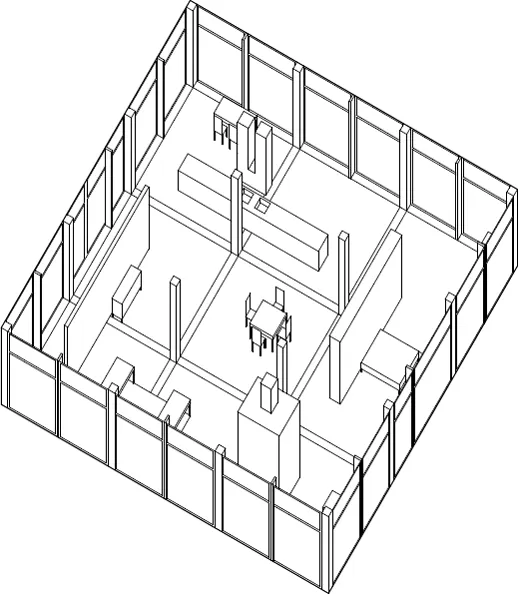

Another central manifestation of the modern in Hejduk’s Texas Houses is the open plan—the Miesian version of Le Corbusier’s free plan—as in House 5 (figure 24). Here the possibility of the open plan comes from the deployment of a square grid, once again in a nine-square composition. The furniture is misaligned, which would be in keeping with the idea of an open plan except for the fact that the arrangement establishes an alternative spatial logic in two ways. First, the furniture is arranged in a square—but one that is shifted off the center of the house. As such, rather than reading the furniture as objects floating within homogeneous Cartesian space, the plan reads as two figures in tension (figure 25). Second, the façades are composed of structural columns that mark the intersections of the nine-square grid, as well as thinner, secondary columns. The latter mark the centerline of the façade bays in ten of the twelve bays. The exceptions are the center bays of the east and west façades. Here the secondary columns are shifted away from the centerline, sliding in opposite directions until the column on the east façade aligns with the center of the square delineated by the furniture, setting the plan into motion as a pinwheel. The pinwheel, however, is immediately arrested by the secondary columns in the north and south façades, which do not move from the centerline of their respective bays.

Hejduk establishes an open plan while at the same time intervening with an alternative spatial logic—the arrested pinwheel—thus freezing the elements of what otherwise would have been a simple open plan. Yet Hejduk remains adamant in the textual description of the project that the house is an explicit exploration of the open plan idea.1 As with the square column, Hejduk works within the vocabulary of the modern in order to explore the limit of its logic. Furthermore, the house is characterized by a dialectical tension between the plan and the pinwheel. The house does not introduce a new syntax, but it finds the potential for tension within a modernist syntax.

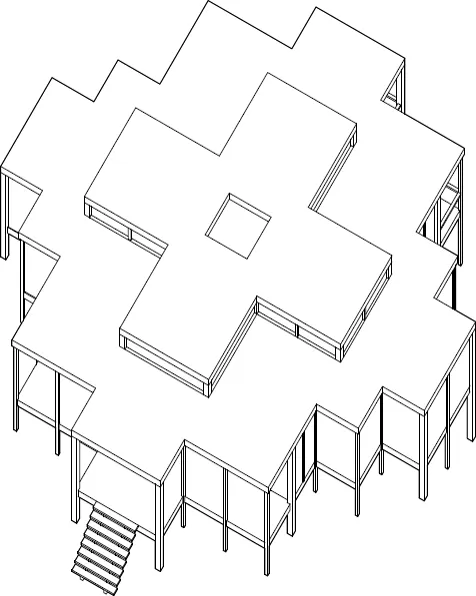

A third example of modernity in the Texas Houses can be found in the strict adherence to the grid that is legible in Hejduk’s treatment of the figure. House 1 (figure 26) consists of a cruciform figure within a field of columns (figure 27). The cruciform rigidly adheres to the logic of the grid and is delineated by a simple change in the height of the walls. As such, rather than challenging the grid through the introduction of an anomalous figure, the cruciform serves to create differentiation between each square of the nine-square. In other words, the modules in the plan, which are both inside and outside the cruciform, are identical in dimension yet differentiated through their position relative to the cruciform. The A-bay is central, while the B-bay is both peripheral and central. The C-bay, in turn, is fully outside the cruciform, and as such, takes on a residual character, despite being fully within the nine-square, which is the dominant geometry of the house. The cruciform and the grid are in constant play—the cruciform is dominant in an axonometric view of the house, whereas in the plan, the orientation of the walls breaks down the integrity of the figure and the nine-square becomes dominant.

Given these readings, it would not be difficult to argue that the Texas Houses challenge the modernist assumptions of Cartesian space by making contradictions possible within its logic.

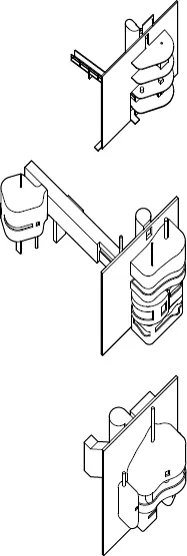

The Wall Houses

Hejduk designed three so-called wall houses (figure 28), and while they all share a vertical surface as a central compositional device, each house takes a different stance on the relation between that surface and the surrounding figures. It could be argued that Wall House 1 is the least problematic. The central wall divides living spaces from circulation, and on one side of the wall a stair core and ramp are attached as volumes, while on the other side, the walls enclosing these rooms are modeled as totally transparent so that the living spaces are expressed as naked floorplates that seem cantilevered from the wall. In contrast, in Wall Houses 2 and 3 each room becomes an independent volume and Hejduk maintains a gap in section between them, such that ceiling planes and floor plates are never shared between rooms. This creates a non-homogeneous vertical stacking (figure 29). This in itself is certainly not a modern convention and yet the formal vocabulary of the Wall Houses is very Corbusian. The figural volumes set against the rectilinear wall are reminiscent of the roof figures in Villa Savoye, the lobes in the Carpenter Center, or the curvilinear rooms of the Mill Owners’ Association Building. Because of this it can be tempting to keep them, like the Texas Houses, within the modernist canon. However, as architectural historian K. Michael Hays has written, “It is apparent that every element of the Wall House comes from the formal repertoire of Le Corbusier (think especially of Villa La Roche and the blank wall at the monastery of La Tourette), and yet our encounter with the Wall House is an experience unassimilable with Corbusian codes.”2 Thus the architecture expresses one of the central characteristics of lateness studied by Adorno in Beethoven: the ability to maintain the outward appearance of form while reformulating the codes that hitherto h...