Because sustainability means different things to different groups and individuals, this makes it sometimes difficult to discuss it, so I’ll just give you my definition. For example, I met a “conservative environmentalist” once who was chiefly focused on climate and carbon issues. His advice to me on my own project, Reveal (a sustainability rating and labeling system for consumers—see Chapter 17), was to measure only climate-related issues (like carbon dioxide production) and leave the social issues for people to figure out on their own. My response was that if customers discovered that the product they believed to be “better” due to the ratings actually had questionable social impacts (such as animal cruelty or child or slave labor), all trust would dissipate for both those products and the rating system.

Therefore, the only way to approach sustainability effectively is from a systems perspective. We need to consider a wide perspective before diving into details. Because most things are connected to most other things, to design anything effectively requires considering what it connects to. This necessitates folding financial, social, and environmental issues together—at least at some point. For sure, these issues are widely different and require specialized knowledge and solutions, but no solution can be addressed effectively without considering its impact across all three areas. You will find, in practice, that you can’t solve everything. However, you will need to be ready to address why you can’t do everything. And, just possibly, in the process you may find that you can address more aspects than everyone around you suspected—which is quite often the result of good design. Constraints are a challenge for designers, not a limitation.

One serious problem for designers is that, even with a systems approach, there are few tools in existence that wrap these issues together. Instead, designers must learn to patch together a series of disparate approaches, understandings, and frameworks in order to build a complete solution. The good news is that these different frameworks are compatible, as you’ll see in Chapter 3, “What Are the Approaches to Sustainability?”. Their vocabulary may be slightly different, but a meta-framework can be built that organizes a coherent and somewhat complete approach to sustainability. This is what I’ve tried to do in this book.

To address the three domains of human, natural, and financial capital, it’s important to understand some of the issues central to each. Different contexts can change the priorities or urgencies of each, but all of these themes are relevant and important to understanding why sustainability is imperative.

You will find, in practice, that you can’t solve everything. However, you will need to be ready to address why you can’t do everything. And, just possibly, in the process you may find that you can address more aspects than everyone around you suspected—which is quite often the result of good design.

Although this is the most important part of the story, it’s still often not good enough for many clients, companies, or business people who just don’t understand why these issues should be dealt with by themselves and their businesses. For them, there is another set of issues that might be more influential in changing their opinions. I won’t go into these in much detail since they aren’t really design issues but following is a list for you to explore further. The better you understand these issues, the more persuasively you can help your company’s and client’s goals align with those of sustainability.

- Even the business press regularly reports on sustainability and social responsibility issues. This not only creates validation for sustainability efforts, but it can also exert important peer pressure on business leaders and managers to “get on the bandwagon” before their competitors.

- At its heart, sustainability is about efficiency. There’s not a manager or leader in the world who isn’t looking for his or her organization to be more efficient. Being able to reduce expenses—especially at a time when costs of almost everything are skyrocketing—is always good business.

- Sustainability is not a fad (changes that are fleeting), it’s a trend (changes that will endure). Whether in the consumer markets or the business markets, more and more customers are concerned with environmental and social issues. There are opportunities for businesses to take advantage of this trend by aligning their brand and promotional efforts with those of the society as a whole—as long as it’s authentic. Otherwise, being exposed for greenwashing is probably worse than not doing anything at all (more about this in Chapter 18).

- Customers, shareholders, investors, and other stakeholders are quickly joining the sustainability wave—no matter how they articulate it. Investors (in particular pension, retirement, and other large funds) are moving their money to investments that align with their longer-term values.

- For many companies, sustainability focuses on risk mitigation (reducing financial and other costs associated with potential risks), especially for insurance, reinsurance, and health-related companies. Any company with a stake in the long term is looking to mitigate its operational and financial risks over that amount of time.

- Governments at all levels are also quickly shifting regulations—especially at the state and local levels—to reinforce and reward organizations that take sustainability seriously. The business world can fight this all they want, but if they lose, they’ll have to make the changes anyway—after their competitors have already mounted the learning curve ahead of them.

What Is a Systems Perspective?

Because sustainability requires a systems perspective, sustainable design must also address the system, whether it is a market, an ecosystem, a social system, or the entire world. This allows the design process of sustainability to address the environment, markets, companies, and people.

It’s easy to understand the concept of a systems perspective: the system is the sum total of everything affected by an activity. A systems perspective requires an appreciation (at a minimum) and an understanding (at best) of how various systems interact with each other. These include environmental, financial, and social systems.

It can be more difficult to understand the boundaries of the systems affected by a particular action and within a particular domain. In addition, measuring these interactions is often faulty, at best. And keeping this perspective in mind during the entire development process isn’t easy. However, it’s possible. You don’t have to create perfect solutions in every way. What you have to do is make conscious, informed considerations across the spectrum of financial, environmental, and social issues, just like you should across the dimensions of customer experience. Your solutions should be better than the baseline (what others devise without considering these issues) and can improve over time.

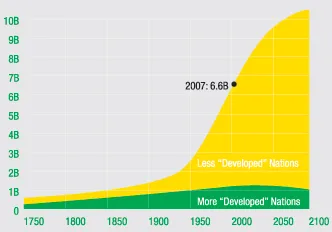

Consider the impact that population has on everything (see Figure 1.1). All issues addressed being equal, the biggest one is probably overpopulation. Solving this one challenge would have the greatest impact on all of the others. If the world had even one-half of the population it presently has, many of our more pressing problems would simply disappear. At half the population, food and resources would probably be abundant. Population, however, takes literally generations to change. If people, collectively, gave birth to only half the number of children now, it would be 40 or 50 years before the effects would truly be visible. And how can we drastically reduce the earth’s population in any socially acceptable way? China instituted a one-child-per-couple policy to great outcry, and its effect has yet to be truly felt. Could that solution be successful in other cultures? What are our other options?

Diversity and Resiliency

Perhaps the best way to judge any system or solution is to assess how resilient it is. Systems that are resilient have a greater chance of lasting, evolving, and responding to change. Nature has evolved and proven to be tremendously resilient, which has allowed it to grow, change, and continue for millennia. Cultures and societies that are resilient have the same attributes. Moreover, each of these systems has a mechanism of resiliency and longevity (such as DNA in nature).

In their book, Brittle Power, Amory and Hunter Lovins define systems that are resilient as able to withstand large disturbances from the outside. They describe several attributes of resilient systems:

- Employs passive behavior

- Employs active feedback (learns and adapts)

- Detects faults early

- High substitutability and redundancy

- Optional interconnectedness (can connect or disconnect when needed)

- Promotes diversity

- Makes use of standardization

- Dispersed

- Hierarchically embedded

- Stable and flexible

- Simple

- Makes limited demands on social stability

- Accessible

Corporations are more resilient organizations since they’ve been granted personhood, limited liability, and immortality (though these can cause other problems). Since corporations can survive their founders, as well as shield their owners from the actions of their managers, they attract more diverse capital and can govern themselves in ways that offer a great deal of flexibility and strategies.

The problem with diversity is that it’s often not valued in society.

Diversity is one strategy for resiliency since it allows multiple solutions and approaches to solve or respond to the same challenge. A diverse community is more able to weather a storm, a bad growing season, a financial hardship, or a cultural crisis. Companies with diverse resources have more tools to respond to market challenges, customer whims, or corporate missions.

The problem with diversity is that it’s often not valued in society. Consider how many varieties of apples (~7500) or rice (~80,000) have evolved. Before humans, these varieties helped all of nature (plants, animals, bacteria, fungi, monera, and so on) respond to often hazardous changes in the environment due to weather, tectonic events, or those from space. Today, however, human societies have reduced the number of varieties of almost everything natural to just a few. The vast majority of the U.S. agriculture system, for example, is built on five to six varieties of apples, three to four types of cherries, and fewer than 20 types of grains—often without even preserving discarded varieties in case we need them in the future. It may seem like good business from a financial perspective (fewer options to choose between), but it’s very bad business if you want a resilient marketplace. Your design solutions and processes will have an impact on resiliency and diversity, and you should consider if that impact is positive or negative.

Resiliency is often missed when evaluating our markets, environments, or systems. Because it’s abstract, we focus on lower-level issues that contribute to overall resiliency, but often don’t address the challenges we face. For example, in trying to solve poverty, we often focus on the symptoms and not the cause. In our fervor, we rush to simple solutions that are standardized because they are easier. We also look for quick fixes to satisfy the urgency we feel. But poverty is not an easy problem to solve. To be effective, poverty needs diverse solutions across the entire system (and often with a long time to take hold). If you want your time and energy to be truly effective, your design solutions will also need to reflect how they contribute to sustainable, lasting, systemic change—not merely the most visible symptoms.

Community resiliency is achieved through a wide spectrum of issues: financial stability and opportunity, diverse education, reliable safety and security, values embedded in systems and markets, and so on. We can’t, for example, ever expect to be safe from terrorism simply by installing alarms and cameras everywhere. Terrorism isn’t the product of anything that can be watched by a camera or triggered by an alarm. Yet, these easy solutions are the ones we jump at, and they provide temporary emotional peace—until they fail. Periodically, you should evaluate whether you’re truly working on a solution at the right level to make the change intended. Often, our projects are defined in terms and at levels that are more easily grasped by organizational functions but aren’t pushing at the pressure points that are needed to make change. Your system perspective is what will guide you to understanding the network of interactions that challenge your customers and clients to determine whether the solution is even capable of affecting the kind of change desired.

Periodically, you should evaluate whether you’re truly working on a solution at the right level to make the change intended.

Centralization and Decentralization

While it’s of...