- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Planetary Mine rethinks the politics and territoriality of resource extraction, especially as the mining industry becomes reorganized in the form of logistical networks, and East Asian economies emerge as the new pivot of the capitalist world-system. Through an exploration of the ways in which mines in the Atacama Desert of Chile-the driest in the world-have become intermingled with an expanding constellation of megacities, ports, banks, and factories across East Asia, the book rethinks uneven geographical development in the era of supply chain capitalism. Arguing that extraction entails much more than the mere spatiality of mine shafts and pits, Planetary Mine points towards the expanding webs of infrastructure, of labor, of finance, and of struggle, that drive resource-based industries in the twenty-first century.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1. OPENINGS

The Mine as Transnational Infrastructure

__________________________________________________________

Introduction

In the early hours of July 21, 2015, nearly 300 subcontracted workers demanding better conditions decided to occupy El Salvador, a copper mine located in the Atacama region of northern Chile. After partially blocking the road to Diego de Almagro—the neighboring town—and shutting down activities at the extraction site, the picketing workers used three Scoop loader machines (heavy haulage equipment employed to move large volumes of rocks) to erect barricades in order to protect themselves from the police crackdown that they viewed as impending. They were not mistaken. On the evening of July 23, a heavily armed contingent of around 120 police and special forces in full antiriot gear arrived and a raging battle broke out. Stones thrown from the barricades set up by these temporary and precarious workers clashed with the rubber bullets and tear gas canisters of the police. After several hours of confrontation, the striking workers mobilized the Scoop loaders they had used to erect the barricades to push back the police’s advance and also to shield themselves from escalating police violence. They had expected considerable repression, but the furious backlash unleashed against them was simply beyond anyone’s imagination. It was as if the police had been possessed by a strange and overwhelming power. “They were pointing infrared beams at us, we were suffocating in tear gas; airgun pellets and rubber bullets were being fired indiscriminately and heavily injuring our comrades,” recalls a worker. After the Scoop machines were drawn into the standoff, the police began to fire live ammunition against the blockade. One of the shots took the life of Nelson Quichillao, who bled to death amid the bitter tears and astonishment of his coworkers, who could barely believe what had just happened.1

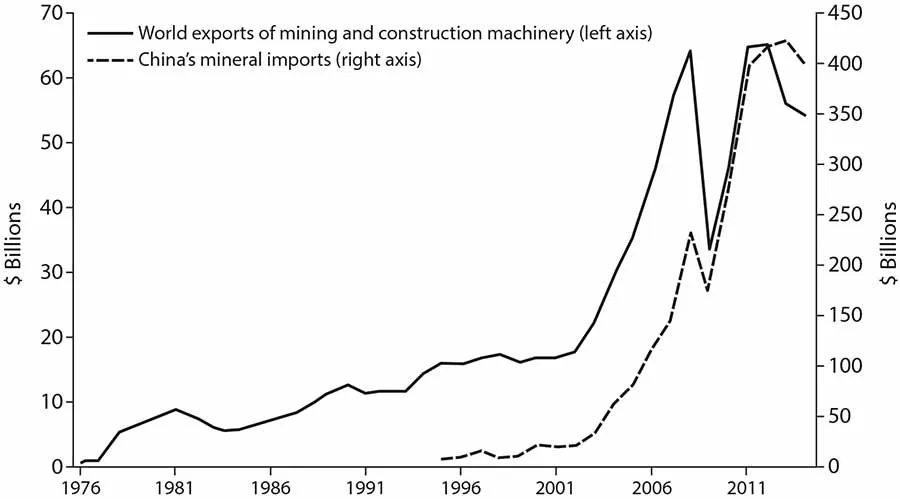

For more than fifteen years, since he was eighteen years old, Quichillao had been working for the mining industry, but he had never managed to obtain a stable work contract that offered him health insurance, paid vacations, and access to a retirement plan, among other benefits that come with salaried work under Chile’s labor regulations.2 Though it was hardly covered by the mainstream media, Nelson Quichillao’s death is far from being an insular or fragmentary event in the swirling complexities of the historical process. In fact, it holds the secret to one of the most fundamental world-historical shifts in late modern society: the staggering acceleration of automation and the concomitant replacement of human laborers with intelligent machines, enabled by a recent leap forward in the whole productive technology of capitalism.3 The tendency to increase the organic composition of capital—that is, the ratio of automated labor to living labor—has been an intrinsic feature of the capitalist mode of production since machinofacturing (the production of machines by machines) became the underlying technical foundation of large-scale industry. Since the turn of the twenty-first century, however, we appear to be witnessing a new stage in the historical struggle of capital against labor, brought about by a new generalized architecture of social production. As figure 1 illustrates, the tendency of the mining industry to become more capital-intensive experienced a dramatic turning point when world exports of mining and construction machinery increased from $17 billion in 2002, to $65 billion in 2012. In Chile, the life and death of Nelson Quichillao thus came to symbolize the plight of temporary and subcontracted workforces, whose ranks have swollen as the mining industry becomes ever more “smart,” “flexible,” and “autonomous.”4 In April of 2016, a trade union named Frente de Trabajadores Nelson Quichillao was created in order to defend subcontracted workers against layoffs and further labor casualization by the mining industry.

Figure 1 World exports of mining machinery and China’s imports of minerals

Source: World Integrated Trade Solution and Atlas of Economic Complexity.

Although in the popular imagination mining is usually considered to be a rudimentary activity, the degree of technological sophistication that mediates the extraction of minerals from the subsoil in the twenty-first century is nothing short of astonishing. Innovations in artificial intelligence, big data, and robotics have allowed mining companies to introduce automatic trucks, drills, shovels, and locomotives to the stages of the production process. Some of these sophisticated machineries—most notably trucks and shovels—are not remotely controlled; they are fully robotized, which means that they can operate twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, without direct human intervention.5 The introduction of geospatial information systems to mineral forecasting and geological surveying has also allowed engineers to produce highly accurate representations of the subsurface, making the extraction of low-grade ore bodies profitable for the first time in history. Mines that had been abandoned are therefore being reopened, and deposits that were deemed uneconomical are being transformed into large open-cast extraction sites across all stretches of the planet.6 Increasing spatial separation of extraction and manufacturing has also pushed the mining industry toward greater functional integration with the port and shipping industries. An erstwhile insular focus on the extraction site has been gradually superseded by a deliberate organizational emphasis on the supply chain, understood as an integrated logistical system that encompasses extraction, processing, smelting, and transport.

This book argues that the mining industry’s recent technological and organizational modernization transcends mere shifts in the intensity and scale of mineral extraction. The planetary mine, I will argue, is the geography of extraction that emerges as the most genuine product of two distinct yet overlapping world-historical transformations: first, a new geography of late industrialization that is no longer circumscribed to the traditional heartland of capitalism (i.e., the West), and second, a quantum leap in the robotization and computerization of the labor process brought about by what I will term the fourth machine age. Since the long sixteenth century, resource booms have been understood as the direct outcome of relations of unequal exchange between an imperial power and a dependent periphery, in the context of a Eurocentric capitalist system. However, the technological modernization and industrial upgrading taking place across the global South after the 1980s—especially in East Asian economies—have decentered the geography of large-scale industry, destabilizing traditional metageographical categories of core/periphery and even of global North/global South.

Throughout this book, I show how geographies of extraction have become entangled in a global apparatus of production and exchange that supersedes the premises and internal dynamics of a proverbial world system of cores and peripheries defined exclusively by national borders. The main contention of this book, therefore, is that the mine is not a discrete sociotechnical object but a dense network of territorial infrastructures and spatial technologies vastly dispersed across space. I build upon Mazen Labban’s notion of the planetary mine as one that vastly transcends the territoriality of extraction and wholly blends into the circulatory system of capital, which now transverses the entire geography of the earth.7 The technological basis of contemporary mining, Labban notes, has blurred the boundaries between manufacturing and extraction, waste and resources, biologically and nonbiologically based industries. This, in his view, warrants the reconsideration of extractive industries beyond the mere wresting of minerals from the soil. I therefore build upon recent approaches that have considered spaces of extraction to also include logistical infrastructures, transoceanic corridors, networks of financial intermediation, and geographies of labor. The reorganization of the mining industry into global supply chains engenders novel modalities of state power and capitalist imperialism and yields a new territoriality of extraction whose immanent content cannot be fully elucidated by the loci classici of state-centric concepts of political economy, such as resource curse, dependency, imperialism, and so forth.

The methodological nationalism that informs most studies of extraction is analytically debilitating because it obfuscates how deeply intertwined global supply chains and sprawling urban systems are in the sociometabolic production and reproduction of the mine; it is also politically counterproductive because it pits the workers and communities of “resource-rich” countries against those of the manufacturing centers, when in fact they all share increasingly common conditions of existence. On this basis, this book makes three central and interrelated arguments. First, it insists on the fact that the concrete determinations that produce spaces of extraction are not relations of unequal exchange and dependency, but the production of relative surplus value at the world scale and the reproduction of the international working class as a fragmented, polarizing, yet unitary whole or industrial organism. In concert with recent work on the new international division of labor and on the new geographies of advanced industrialization, it uses resource extraction as an analytical entry point to theorize uneven geographical development after the Western phase of capitalism. Second, it argues that the determination of capital as a genuinely global form of social mediation does not entail falling into the hyperglobalist fallacy that posits the erosion and withering away of state sovereignty. The political authority that underpins the international movement of capital continues to be mediated nationally; hence the existence of the planetary mine signals the emergence of a more coercive, centralized, and authoritarian configuration of late neoliberal statecraft.

Finally, Planetary Mine contends that understanding the manifold determinations that produce landscapes of extraction in historically and geographically specific ways necessitates a dialectical theory of praxis, one that sets out from the material conditions in which life itself is produced and reproduced. As the young Marx argued, “Sense perception must be the basis of all science.”8 It is by interrogating sensuous practice that we become better positioned to grasp the manifestations of the mystifying forms, the immanent rhythms, and the inner contradictions of the capitalist economy and bourgeois society in its totality. At the heart of this book’s intellectual project is therefore an attempt to reclaim “form-analysis Marxism,” a strand of critical thought that has remained peripheral to the development of historical-geographical materialism and urban political ecology but has much to offer to these vibrant fields of inquiry.9 A focus on the forms or modes of existence of capital rather than on “structures” allows us to supersede subject-object dualism, and henceforth capture the universal content that is expressed through the unfolding of concrete practices and things.10 To the extent that it seeks to decipher global processes through their concrete manifestation in the situated, affective fabrics of human and nonhuman existence, this mode of theory-building strongly resonates with the aspirations of approaches such as standpoint feminism and minor theory.11

Under a categorical approach that roots the dialectical critique in experience, the gendered and racialized migrant toiling in the popular economies of a mining town no longer appears as an isolated fact of social reality, but embodies deep reconfigurations in the social composition of the global working class and the relative surplus population; the robotized systems of extraction wresting copper from the bowels of the Andes begin to reveal the metabolic process that underpins the startling growth of megafactories and industrial cities in East Asia; the credit cards in the hands of peasants living near remote extraction sites crystallize fragments of the hulking figure of “casino capitalism” and its complex global architectures for the organization of monetary flows. But perhaps most importantly, an emphasis on forms also foregrounds the impermanence of things and the contingent nature of reality. Thus, in the alienated movement of the clockwork mechanical systems of extraction—themselves a form of existence of capital as it transitions through its phases—we can also begin to perceive the early stirrings of a future society where technology no longer presents itself as a hostile, quasi-autonomous power, but can instead irradiate and nurture life. An approach that takes seriously the analysis of modes of existence, Postone argues, necessarily points toward such alternative futures, where content is stripped of its distorting capitalist forms and can finally come into its own.12

Natural Resource Frontiers after the Western Phase of Capitalism

Europe, Achille Mbembe suggests, has ceased to be the structuring center of human civilization, and this fact constitutes the most fundamental experience of our time.13 The downgrading of Europe into one among several other world provinces, Mbembe considers, opens up new possibilities and horizons for critical thought. Perhaps one of the most relevant of these horizons consists in identifying the attributes of capital as it transforms into a sociomaterial form of life whose scale is, for the first time, truly planetary. Although, in the Grundrisse, Marx points out that the tendency to create the world market is intrinsic to the very concept of capital,14 this potentiality was not fully actualized until very recently. Indeed, major Marxist theories of imperialism emerging in the context of the Second International and beyond were tacitly or explicitly premised on the assumption that capitalism was a relatively local phenomenon. Figures such as Luxemburg, Lenin, and Hilferding considered imperialism the means by which this local, Western organism (capital), interacted with its noncapitalist outside (non-Western peripheries) by means of military conquest, pillage, and colonial domination, basically in order to sustain its own process of “expanded reproduction.” Recent transformations in the geographies of capitalist industrialization, however, warrant a reconceptualization of the scale at which this process operates. According to Cammack,

The commonly quoted assertion that growth has been slower since 1973 than before is true for the West, and for the world as a whole. But Asia is the exception. Add to this the observation that the “world market” envisaged by Marx and Engels only a century and a half ago only came into being in the 1990s, and it is reasonable to suggest that far from it being the case that capitalism is a “Western” phenomenon, its “Western” phase, protracted though it seems from the point of view of the present, has merely coincided with its pre-history as a genuinely global form.15

The idea that capitalism has become emancipated from its traditional heartland and global in its geographical extent is epochal, and has brought back old debates on the “new international division of labor” (NIDL).16 After being highly influential when originally formulated by Folker Fröbel, Jürgen Heinrichs, and Otto Kreye in 1977, the NIDL thesis fell out of favor in the late 1980s. In the face of declining profitability and increasing labor unrest, Fröbel et al. argued,17 companies embarked on a process of global organizational restructuring that involved relocating industrial production to “Third World” countries. Critics argued that there was nothing essentially new about the NIDL because, although many Third World countries were no longer exporting raw materials but manufactured goods, the processes that had been spatially relocated involved low-skill, labor-intensive tasks, so the hierarchical international system, structured around Western cores and their dependent peripheries and semiperipheries, remained intact. The startling industrial upgrading that began to take place after the 1990s, especially among first- and second-generation “Asian Tigers” (Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore), which later built up to the spectacular rise of China, put into question the geometries of power inherited from the classical world system.

Ever since the long sixteenth century, and as authors in the world-systems-analysis tradition show, historical cycles of accumulation have been underpinned by scientific-techn...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Table of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Openings: The Mine as Transnational Infrastructure

- 2. Empire: Resource Imperialism after the West

- 3. Labor: Bodies of Extraction and the Making of Urban Environments

- 4. Circulation: State Power and the Logistics Turn in the Extractive Industries

- 5. Expertise: Technocracy and Expropriation

- 6. Money: Debts of Extraction

- 7. Struggle: Plebeian Consciousness and the Universal Ayllu

- 8. Epilogue: Toward an Emancipatory Science in the City of Extraction

- Notes

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Planetary Mine by Martín Arboleda in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Political Economy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.