![]()

SELF-HELP’S PORTABLE WISDOM

A “THIN CULTURE”

When discussing self-help, intellectuals tend to begin with the bad: self-help as an instrument of neoliberal governance, a tool of systemic oppression, or an agent of colonial subjection. For a change, this chapter begins with the good. In addition to being a “technology” used to discipline citizens and manage populations (see Foucault and Rimke),1 self-help has historically served another, curatorial function: to mine, collate, and reorganize the archive of textual counsel for the purposes of inspiring self-transformation. If the literary text is a “tissue of quotations,”2 then the self-help book is even more so. The genre’s manic citational practice is already operative in the case of Samuel Smiles’s 1859 Self-Help, the central case study of this chapter, which uses quotations from authors as various as William Shakespeare, John Milton, John Keats, Walter Scott, John Ruskin, and John Stuart Mill, and it carries through to Dale Carnegie’s zealous collating of the life advice of thinkers from Sigmund Freud to John Dewey, Dorothy Dix, William James, and Lin Yutang. As I’ll show, Smiles’s Self-Help offers a keyhole into self-help’s embroilment in translation, popularization, and canon formation. In a striking example of self-help’s cultural authority, countless readers in Britain and beyond first encountered the classic literature of the West through Smiles’s Victorian handbook. In late nineteenth-century Meiji Japan, for example, Self-Help was so influential that the authors it praised became instant sensations, whereas the authors it neglected to mention remained largely untranslated.3

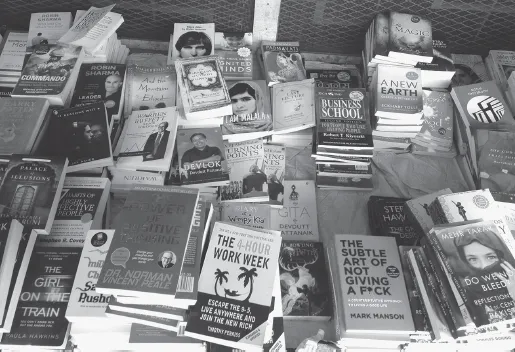

Patricia Neville laments that “perhaps one of the most glaring omissions from the self-help book canon has been the absence of globalization, either as a theorizing construct or operational framework against which we could chart, plot, and measure the breadth and width of contemporary self-help book culture.”4 In the interest of redressing this gap, I have assembled a motley community of readers who have used self-help texts such as Smiles’s as occasions to articulate a critical perspective of Western modernity’s key tenets. Early self-help, and the patchwork, didactic hermeneutic it advocates, defined individuals’ first experiences with literary works and acquired the status of a gateway to cultural literacy around the world. Self-help’s globalized presence has only intensified over time. New York Times writer Azadeh Moaveni observes that, in Iranian bookstores, “self-help books and their eclectic offshoots, on topics like Indian spirituality and feng shui, enjoy the most prominent position.”5 In Egypt, notes Jeffrey T. Kenney, the self-help industry has grown “dramatically” since 2000, with both Islamic self-help authors and translations of works by Carnegie, Tony Robbins, and Rhonda Byrne, among many others, stocked on local shelves.6

Research into self-help’s global reception reveals that “culture in action”7 does not operate through a unilateral movement from source to recipient—as reception theory traditionally claimed—but through a complex and ongoing process of negotiation, qualification, and selection. Sociologist Paul Lichterman proposes the term thin culture to describe the “shared understanding” among self-help readers that “the words and concepts put forth in these books can be read and adopted loosely, tentatively, sometimes interchangeably, without enduring conviction.”8 In opposition to accounts of the genre’s homogeneous neoliberal influence, he explains that we should not “assume in advance that we know how strong or how unified an ideological message it is that self-help book readers read out of their books, nor that they are passive receivers of what “ideologies” they may read out.”9

Self-help books in a street market in old Delhi.

Credit: Leah Price, 2018.

The self-help hermeneutic binds this global community of utilitarian readers, whose first encounters with such popular manuals often occur at critical historic junctures when traditional cultural values are upended.10 To give just a few examples, self-help activity spiked in Japan following the 1867 collapse of the Tokugawa shogunate, which created an urgent demand for shortcuts to the modernization that the country had closed itself off from for over two hundred years; it flourished in Ghana and Nigeria in the years leading up to independence (1957 and 1960, respectively); and it is exploding today in the post-socialist People’s Republic of China, where the ideology complements the society’s intensely competitive market economy.11 It would be easy to bemoan self-help’s influx during such transitional periods as the opportunism of Western capitalism inserting itself into a vulnerable and impressionable populace. Yet for such nonsynchronous communities of readers, self-help culture is not received in the form of a monolithic and authoritarian ideology to replace the political ones only just overcome, but adopts the portable, objectified status of an “objet trouvé.”12

It is time to bring together the wealth of sociological data regarding self-help reading practices around the world, practices that raise germane issues of bibliography, reception, circulation, and cultural exchange, and to place this data in conversation with literary studies. In this chapter, I argue that Smiles’s Self-Help initiated a pattern of cultural transmission through self-help literature that continues to be strong into the present day. The book’s reception furnishes a portal onto the mechanisms of literature’s transmission through vernacular genres around the globe. Self-help not only transmits literary culture but also introduces an element of taxonomic confusion into preexisting institutional bibliographic arrangements. This unsettling of generic and cultural classifications implemented by self-help’s early readers has become a formal strategy of contemporary novels, or what I call “how-to fictions,” and is exemplified by Tash Aw’s Five Star Billionaire (2013), the subject of this chapter’s concluding sections. Hybridized novels like Aw’s reveal that the pastiche methodology of self-help’s first readers has become a mainstream conceit of contemporary novelists. Self-help has become a transmedia industry that implicates us all—aesthetes and entrepreneurs, critics and lay readers—in its expanding cultural matrix.

THE SMILES HEARD ROUND THE WORLD

When Smiles self-financed Self-Help in 1859 (the same year Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species appeared), it quickly became an international sensation even though, Smiles confessed, “there was nothing in the slightest degree new in this counsel, which was as old as the Proverbs of Solomon, and possibly quite as familiar.”13 Samurai in Japan reportedly camped out overnight to buy a copy, earning Self-Help the moniker “The Bible of the Meiji.”14 And Smiles loved to recount that the khedive of Egypt inscribed his maxims on his harem walls, right beside lines from the Qur’an.15

The choppy structure of Smiles’s text, composed of more than three hundred biographical sketches, maxims, and anecdotes, invited the portable, serendipitous reading methods more commonly associated with biblical sortes (chance selections of the Bible). But perhaps the most striking feature of Smiles’s text is its unabashed reliance on very long and tedious lists that rival anything found, for example, in Joyce’s Ulysses. Self-Help includes endless catalogs of successful men (only men) who rose from obscure origins to achieve professional recognition:

The common class of day-laborers has given us Brindley the engineer, Cook the navigator, and Burns the poet. Masons and bricklayers can boast of Ben Johnson, who worked at the building of Lincoln’s Inn, with a trowel in his hand and a book in his pocket, Edwards and Telford the engineers, Hugh Miller the geologist, and Allan Cunningham the writer and sculptor; whilst among distinguished carpenters we find the names of Inigo Jones the architect, Harrison the chronometer-maker, John Hunter the physiologist, Romney and Opie the painters, Professor Lee the Orientalist, and John Gibson the sculptor.16

Contemporary readers may be incredulous that a book so popular could contain so many dry and lengthy catalogs. But Smiles’s readers found these inventories anything but dull; their sheer quantity intensified and substantiated Self-Help’s thrilling promises of upward mobility. Smiles’s emulative heuristic, which resonated so forcibly around the world, is communicated as much through the book’s form as through its content. Indeed, self-help’s almost mystical veneration of the transcendent power of the list to conjure one’s desires is already germinating in Smiles’s inventories. This power of the list eventually came to be exploited by cult best-sellers such as R. H. Jarrett’s 1926 “little red book” It Works, which guides readers toward making their “dreams came true” through the composition of successive lists of their goals that they are then instructed to review and repeat several times a day.17 From Franklin’s list of virtues to Smiles’s inventories to Reddit’s listsicles, the list has become a staple of self-help discourse.

Though Smiles’s book helped to lay the groundwork of the contemporary improvement handbook, it was also very much a product of the self-culture of its time, whose other proponents included G. J. Holyoake’s Self-Help by the People (1857) and Timothy Claxton’s Hints to Mechanics on Self-Education and Mutual Instruction (1833), among others.18 Although self-help is typically assigned Anglo-American origins, an important precedent being John Lillie Craik’s 1830 The Pursuit of Knowledge Under Difficulties, Illustrated by Anecdotes,19 two of Smiles’s most influential models were French: Louis Aimé-Martin’s Education des Meres de Famille [The Education of Mothers] (1840) and Baron de Gérando’s Du Perfectionnement moral, ou de l’Éducation de soi-même [Self-Education: Or the Means and Art of Moral Progress] (1833), which was also a key influence on the New England transcendentalists.20 In addition, as Vladimir Trendafilov’s careful genealogy indicates, the phrase “self-help” had precedents in the writings of Carlyle and Emerson, and likely was coined in an editorial by Smiles’s predecessor Robert Nicoll in the Leeds Times of September 3, 1836.21

Self-Help’s serial pedagogy and investment in the drama of upward mobility found parallel expression in the Victorian Bildungsroman which sometimes extended (Adam Bede) and sometimes parodied (Great Expectations) Smiles’s approach.22 But one of many significant differences between Self-Help and the period’s fiction concerns their opposing stances on the aesthetic merit of failure. Early critics of Smiles’s book objected to its focus on men who have succeeded and its neglect of those who have floundered: “Why should not Failure,” they asked, “have its Plutarch as well as Success?” Smiles responded: “Readers do not care to know about the general who lost his battles, the engineer whose engines blew up, the architect who designed only deformities, the painter who never got beyond daubs,”23 a point that key practitioners of the novel genre, such as Gustave Flaubert and George Eliot, seemed determined to disprove.

For this reason, Victorianists often read Smiles’s book as a foil for the period’s success-wary fiction. A striking example of this dynamic is Dickens’s “anti-Cinderella story,” as Jerome Meckier calls Great Expectations, which is read as an inquiry into the moral quandaries and inevitable disappointments raised by the dramatic social ascent Self-Help promises. Tellingly, as Meckier notes, Self-Help sold twenty thousand copies in its first year, compared to the 3,750 copies sold of Great Expectations.24 Smiles’s sales “far exceeded those of the great nineteenth-century novels,” Asa Briggs observes.25 There are numerous intriguing examples of rivalry and exchange between Smiles’s Self-Help and the period’s fiction, but a lesser-known Smiles rebuttal is found in H. G. Wells’s 1894 story “The Jilting of Jane,” about a servant girl whose fiancé William, a second porter in a draper’s shop, reads a copy of “‘Smiles’ ‘Elp Yourself’” given to him by his employer, which inspires him to adopt the posture of a gentleman and abandon his promise to poor Jane in favor of...