![]()

THE SILENT SCREEN, 1895–1928 Scott Curtis

Within twenty years, from around 1908 to 1928, American animation grew from an intermittent series of experiments and curiosities to a full-fledged arm of the motion-picture industry. As countless articles and interviews proclaimed, animation involved a lot of work; it was precisely this hard labor that shaped the raw idea of animation into a viable commercial product. Key to this transformation was a shift in animation’s mode of production. Animators, such as Winsor McCay and Emile Cohl, were prodigious draftsmen, capable of creating an animated film almost entirely on their own, sometimes within weeks. They worked essentially as individual craftsmen in an artisanal mode of production: they produced animations on their own, mastering themselves (or with minimal help) all the different tasks required. But during and after World War I, such animators as J. R. Bray adopted technological innovations (e.g., reusable celluloid sheets) and new managerial methods (e.g., a division of labor among many animators) to create an industrial mode of production: animation produced on an “assembly line” of sorts with discrete tasks divided among a team of specialists. This shift allowed animated films to be made in a timely way to meet distributors’ quotas and to be shown in theaters on a regular basis; animation became a standardized and reliable commodity. It also changed the way animation looked; the graphic and cinematographic style of animation changed over the course of two decades and would continue to change. But the standard approaches to commercial animation—mostly drawn animation, as opposed to object or other sorts of animation—were established during this era. The solutions to the problems that animators faced in making films were set during this crucial period. This chapter will provide an overview of these problems and solutions and of the technological, managerial, and stylistic changes to American commercial animation before the coming of sound to the motion-picture industry.

American commercial animation in the silent era emerged from a variety of cultural practices, forms, and genres. Before the mid-1910s, animation as we know it was not a regular feature of the popular entertainment landscape. Indeed, what we understand to be an “animated cartoon” was not recognized as such by either the industry or its audiences at this time. This was due partially to the relative scarcity of such films before 1914. But it was also due to the prominence of another, related genre that audiences did recognize: the trick film. Trick films featured a surprising substitution through a cinematographic or editing sleight of hand: as the action before the camera played out, the actors and the camera could be stopped; a substitution (such as a female for a male) could be made, and the action and camera resumed; it would then appear on-screen as an instantaneous, even magical transformation. France’s George Méliès was the acknowledged master of the trick film genre, also often known at the time as a “stop film,” because the camera literally stopped before the substitution and resumed again. Animation is built on the principle of the stop film, except that it continues to stop in serial fashion, rather than for a single isolated substitution; that is, it stops and resumes frame by frame. So for pre-1914 producers and audiences, the few films that employed frame-by-frame animation were clearly “trick films.”1 The first films that contained true frame-by-frame animation featured a limited application of the stop-motion technique to make objects move on their own, as in such films as James Stuart Blackton’s The Haunted Hotel (Vitagraph, 1907) or Edwin S. Porter’s The “Teddy” Bears (Edison, 1907).2 (Indeed, even today any animation that uses objects or puppets is known as “stop-motion” animation.) But as animated films became more elaborate, their extreme novelty and flamboyant technical expertise surpassing most trick films, and as they became more common, they became recognized as something else: “animated cartoons.” We might even speculate that the preference for drawn animation over object animation in post-1914 animation also facilitated this new recognition; trick films before had been almost entirely associated with object movement and substitution, whereas drawn animation was clearly something different. This change in recognition accompanied a shift in the mode of production as well: by 1920, drawn animated cartoons were often made according to an industrial model, at a larger scale, so they occupied more and more of the theatrical program, meaning that they were produced, packaged, and sold as a category unto themselves. “Cartoons” became a genre of motion picture in the American industry.

“Cartoons” as a term brings up the thorny question of the exact relationship between animated films and drawn cartoons, the kind published in magazines and newspapers. This is not the place to rehash the debate, only to say that the relationship is not as straightforward as it might initially appear.3 It is not entirely clear, for example, that the temporal sequence or relationship between panels that we find in drawn cartoons had a direct influence on the formation of editing conventions in animated cartoons. We can say with confidence, however, that early animation and live-action films in general owed quite a lot to the ready-made storehouse of gags, characters, and story material in cartoon strips of the day.4 But there was not even an attempt to translate a cartoon strip into an animated film until Winsor McCay adapted his own strip Little Nemo for a one-reeler in 1911. It took another two years for an adaptation of a comic strip—George McManus’s The Newlyweds, released by Éclair in March 1913—to appear in theaters. The success of The Newlyweds emboldened print cartoonists to lend their signatures to this new format, and comic strip–based series of animated cartoons were much more common. Again, this may have been due to the change in mode of production that allowed more efficient production of drawn animation. But it is also true that the pioneers of drawn animation—and hence, in many ways, the animation industry—virtually unanimously had experience in cartooning, editorial illustration, or other forms of graphic arts.5 This meant that these draftsmen (and they were almost universally men) came from a tradition that not only provided handy fodder for gags and characters, which they could adapt for a new medium, but also trained them to draw quickly and efficiently, which would be absolutely vital to their success as they attempted to generate the thousands of images necessary for a single animated film.

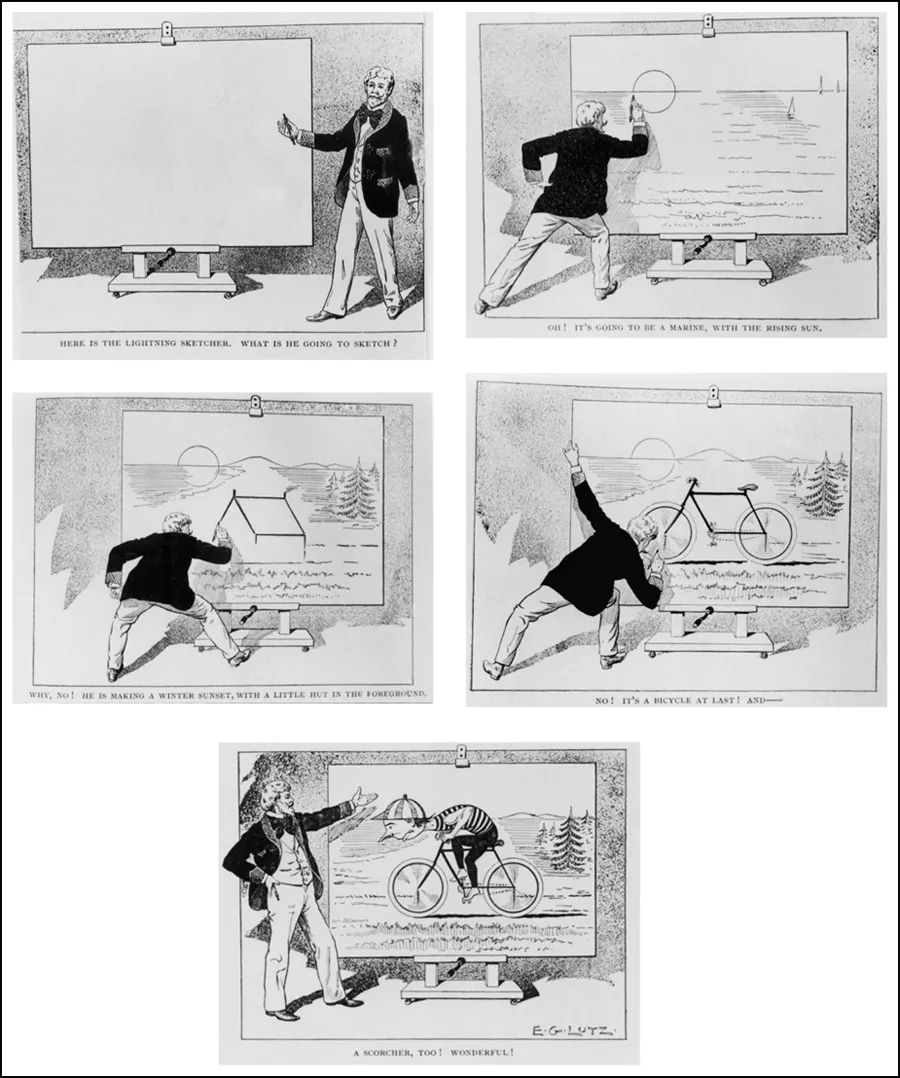

However, in terms of the conventions or iconography of animation during its early period (1908–1913), the vaudeville lightning sketch is perhaps the most important influence. This popular act on the vaudeville stage featured a quick-draw artist who, with a few careful and choreographed strokes of his crayon on a white board, could effect the most startling and amusing transformations of objects and caricatures. A drawing might start out as a sunset, then become a house on a lake, and with a few extra quick strokes turn into a young boy on a bicycle (fig. 1.1). What would this stage act have in common with early animation? First, in a purely practical sense, the quick and sure drawing skills necessary for this act would translate well to the requirements for making an animated cartoon—and two of the most adept lightning sketchers, James Stuart Blackton and Winsor McCay, would become the pioneers of American animation. Second, the convention of instant transformation of objects into something else would become a standard convention in animation as well. Metamorphosis is perhaps the single most important convention of drawn animation; it starts with this practice in lightning sketches. Third, the stage presence of the lightning sketcher translated into early animation as the convention of self-figuration: over and over again in animation, we find “the hand of the artist,” as Donald Crafton calls this familiar iconography.6 That is, in early animation, it is common to see the animator begin to draw the figures before the figures come to life. The lightning sketch, Crafton claims, was “the mechanism by which self-figuration first occurred.”7 Fourth, early animators often adopted the conventions of the stage in other ways, especially in choosing to present animation as an illusion or magic. Film could indeed bring objects and drawings to life, it seemed, and the urge to present oneself as a conjurer was irresistible. Animator as magician was one of the major tropes of the early period, at least partially owing to the stage practices of lightning sketchers.8 A film such as Blackton’s Humorous Phases of Funny Faces (1906) exemplifies these practices in the way it presents its animation as a stage illusion, its sudden transformation of the faces, and its presentation of the artist as the creative force behind this startling metamorphosis. So the conventions, iconography, and practices of trick films, comic strips, vaudeville, and lightning sketches all contributed to the shape of early animation, which we will explore further in the next section.

FIGURE 1.1: Edwin G. Lutz, The Lightning Sketcher, Life (April 15, 1897).

The Artisanal Mode, 1908–1914

If trick films, comic strips, vaudeville, and lightning sketches all shaped early animation, a good deal of our understanding of animation’s integration of these forms comes from our acquaintance with Emile Cohl and Winsor McCay, two animators who perhaps best exemplified the merger of these various cultural practices. Cohl enjoyed fame as a caricaturist in France before he made Fantasmagorie (1908), which is arguably the first drawn animated film. After Fantasmagorie, Cohl worked for Gaumont in Paris for many years, producing many animated and trick films, before coming to the United States in 1912 to make an enormously influential animated series, The Newlyweds (1913–1914).9 Indeed, Cohl’s inventiveness and prodigious output makes him most responsible for transforming the early trick film into the animated art form we recognize today.10 McCay, too, was one of the most famous cartoonists of his era; he worked as an editorial cartoonist for New York newspapers and also created several successful comic strips, including Dream of the Rarebit Fiend (1904–1911) and Little Nemo in Slumberland (1905–1911). In addition to drawing cartoons, he also appeared frequently on the vaudeville stage, first as a lightning sketcher around 1906 and then as a multimedia act combining his drawing and filmmaking talents. Cohl and McCay employed much different methods, but they also faced common problems as artisanal animators: how to generate images in a timely and efficient manner; how to ensure smooth continuity of movement from frame to frame as they drew; and how to ensure that the images remained stable from frame to frame without jumps or gaps as they photographed them. These problems were related to each other in the drawing and photographing processes, and they were not the only problems they faced, but the solutions they developed would be significant and useful for all animators for decades afterward. This section, then, will describe the artisanal approach to animation, the problems McCay and Cohl faced, the solutions they decided upon, and how these problems and solutions affected their animation style.

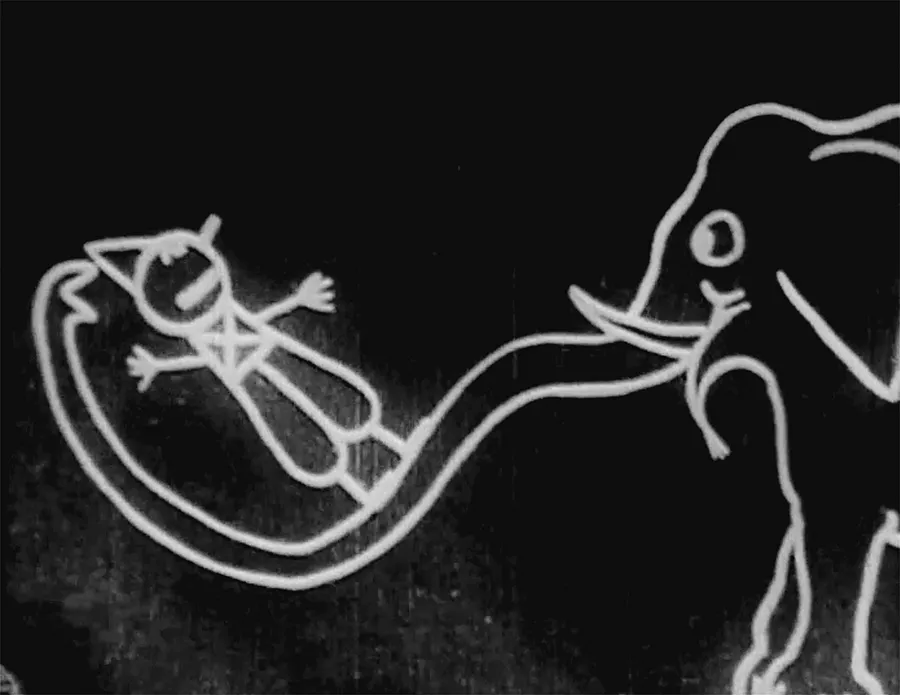

FIGURE 1.2: Fantasmagorie (1908).

Cohl made films in the artisanal mode throughout his career: between 1908 and 1921, Cohl animated more than 250 films, which he designed, animated, and photographed single-handedly.11 Fantasmagorie was the first of these handcrafted gems. Its white lines on a black background—accomplished by drawing black lines on white paper, exposing the film, and then printing the film in negative—are perhaps an homage to Blackton’s Humorous Phases of Funny Faces, which used a black chalkboard for its images (fig. 1.2). To extend this homage, Fantasmagorie begins with the image of the animator’s hand drawing the protagonist; the hand of the artist leaves the frame, and the drawing comes to life. Blackton’s lightning-sketch performance has now been figured into the film proper—a trope that would last for decades in one form or another; the “hand of the artist” trope is probably the most common convention of early animation. The film is just over a minute long—thirty-six meters in length—and Cohl claimed it required 1,872 drawings, which is the equivalent number of frames in thirty-six meters of film. But close analysis shows that it required only 700 separate drawings, which he traced and retraced on a light box.12 The difference is in the number of frames he exposed per drawing. If he had exposed one image per frame, then he would have required that many separate drawings. But Cohl decided to expose two frames of film per image, thereby cutting his work in half.13 This shortcut, now called shooting on twos (or “on threes” or “on fours,” depending on how many frames are exposed per drawn image), is common practice for animators hoping to cut the number of images generated; rather than sixteen drawings per second (a common projection speed in the silent era), for example, Cohl needed only eight drawings if shooting on twos.

But the most striking feature of the film is its sense of spontaneous play and metamorphosis. The narrative, such that it is, changes as the figures transform into other figures or objects. This playfulness is a product of Cohl’s approach to animation: rather than meticulously plan ahead each movement, Cohl started with his first image and simply ...