![]()

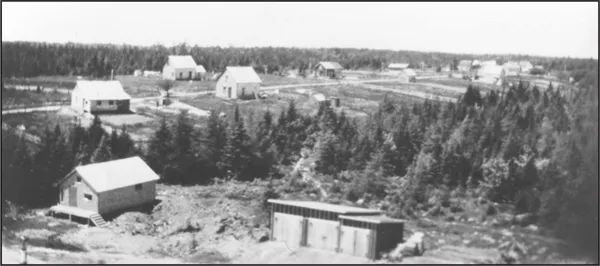

Caribou Mines

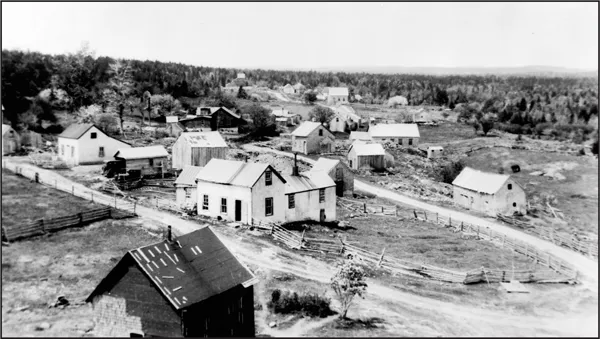

Looking northwest across Caribou Mines, Halifax County, c. 1935

“Just about the close of the fiscal year of 1864, a gold discovery, believed to be of importance, was made a few miles to the rear and southward of Upper Musquodoboit. The auriferous quartz brought from this locality was very rich and … the prospects of the place as a mining district promising.” The district referred to in this 1865 provincial mines report was Caribou (now known as Caribou Mines), which between 1869 and 1968 produced 91,335 ounces of gold, the second highest output among Nova Scotia gold districts.

Josiah Jennings and a Mr. Harrington are thought to have been the first to find gold at Caribou (spelled Cariboo on official postal stamps) in 1864 while hunting with Mi’kmaq guide Francis Paul. No one knows how the community was named, which originally was part of neighbouring Musquodoboit. Some say it was because of the large caribou herds that once roamed the barrens nearby, while others credit John “Cariboo” Cameron (1820-1888), from Ontario, who made his millions prospecting gold in British Columbia before moving about 1870 to the Nova Scotia gold district that possibly bears his nickname.

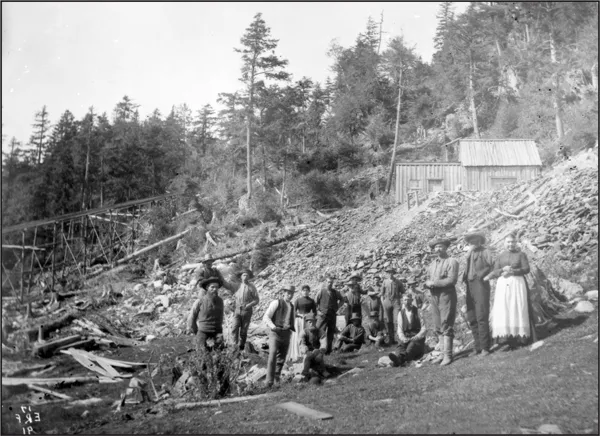

Elk Gold Mine at Caribou Mines, 1897

A consortium of Truro businessmen, headed by George Stuart from Middle Musquodoboit, opened the Elk Mine in 1884. Stuart worked claims off and on at Caribou Mines between 1863 and 1908. Of special interest in this photo are five barrels on the roof that held water in the event of fire.

Nova Scotia had a worldwide reputation for the purity of its gold, 98 percent pure, which was considered “unusually high.” According to the 1897 edition of Canadian Mining, Iron and Steel Manual, “The area of gold measures in Nova Scotia has been estimated by various authorities to be from 5,000 to 7,000 square miles or from one-fifth to one-third the area of the Province, yet the actual area from which the gold thus far obtained has been won is less than 40 square miles.”

Wyatt Malcolm of the Federal Department of Mines Geological Survey Branch reported in 1912, “There are not nearly as many gold districts in the western half of the field as in the eastern and few have proved as productive as those in the east.”

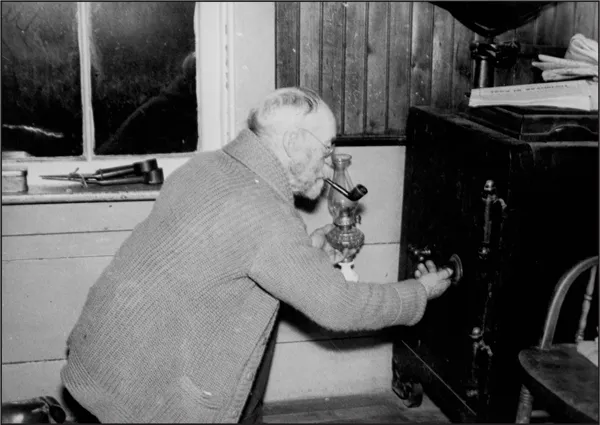

Prospector Matt McGrath locks up his “gold poke” for safe keeping c. 1950

Three-quarters of the 65 gold districts declared between 1862 and 1935 were in Halifax and Guysborough Counties. As to the number of men employed, a breakdown by county is not available. However, the first federal census in 1871 reported 568 miners working in Guysborough, Halifax, Hants and Lunenburg Counties. Then 14 of the 17 gold districts were in Halifax and Guysborough Counties, so it is reasonable to assume these two counties would have had the majority of miners as well.

Comparing the 1881 federal census results with those of 1871, the number of miners remained virtually unchanged. By 1897, however, the Canadian Mining, Iron and Steel Manual claimed there were as many as 4,000 people “dependent to a great extent, or entirely, upon the industry” in Nova Scotia. In 1901, there were more than 800 gold miners listed in the census, with an annual mean salary of $262. A downward spiral soon followed, dropping by more than 50 percent to 357 miners in 1911, then to only 153 by 1931. There was a short-term spike province-wide in 1941 to 605, before falling off dramatically by the decade’s end.

At the time of this 1950s photo, prospector Matt McGrath from Wine Harbour, Guysborough County, was one of only 23 men in all of Nova Scotia still working claims.

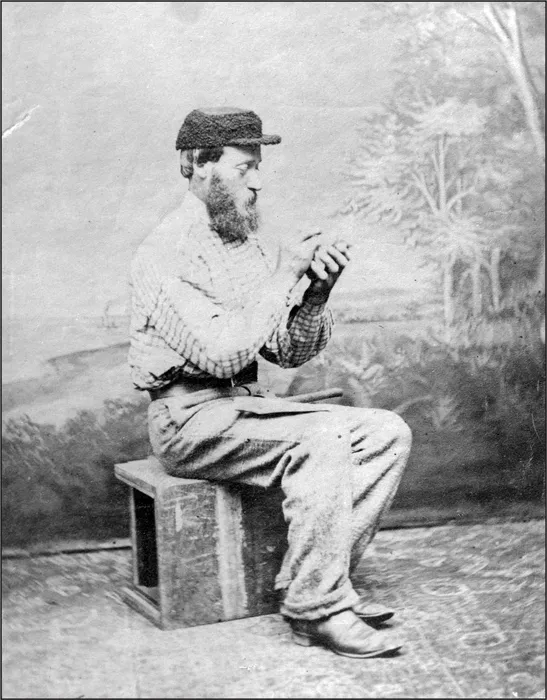

Prospector John Gerrish Pulsifer of Musquodoboit, 1860

Who first discovered gold, where and when in Nova Scotia is subject to debate as history speaks of both “unofficial” and “authenticated” finds dating to the early nineteenth century. There are accounts from the mid-1800s of labourers digging up pieces of gold when building roads and tilling fields, as well as British army officers from Halifax chancing upon auriferous rock while hunting moose. Most remained oblivious to their good fortune as gold’s identifiable traits were still largely unknown to Nova Scotians. Stories tell of men whittling the malleable precious metal to pass time or dismissing it as “rubbish” and going about their business.

With gold rumours circulating in 1858, the Nova Scotia legislature took control of all mines and mineral rights in the province. Two years later, John Gerrish Pulsifer, a Musquodoboit farmer turned prospector, ignited the first of three gold rushes when he found gold-bearing quartz on the Tangier River at Mooseland in Halifax County with the help of Mi’kmaq guide Joe Paul, perhaps a relative of Francis Paul of Caribou gold fame. Fuelled by distant tales of Eldorado from earlier strikes in California (1848), Australia (1851) and British Columbia (1858), gold hysteria consumed Nova Scotia between 1861 and 1874. Claims were quickly staked and mining companies organized, with British and American investors supplying 93 percent of the financial backing.

Six hundred men descended upon Tangier in 1861, where 100 mining leases were frantically worked, each costing $20 and measuring a scant 50 feet by 20 feet. By 1862 the chaos and press of humanity was so great that provincial mining authorities intervened. On the pretense of protecting landowners, the government declared Tangier a “gold district,” one of 17 to be established by the early 1870s, imposed lease rental fees and collected 30 percent royalties on gold recovered.

Despite the potential for raucous behaviour, most gold districts were surprisingly tame. Reporting on Tangier in 1861, The Illustrated London News wrote of how “the universal civility and good manners of its inhabitants would certainly hardly agree with the notions of the character of the gold-digger.”

As the initial euphoria of gold fever dissipated, farmers wielding “crude appliances” such as hammers, picks and shovels awoke to the stark reality of the arduous task at hand. When nuggets for the taking proved elusive, many men left the gold fields for the harvest fields of home. Due in large measure to “poor mining methods, bad management and incompetency” gold lost its lustre. From a high yield of 27,538 ounces in 1867, production dwindled province-wide to only 9,140 ounces by 1874, at which time mines closed, companies folded and a decade-long silence fell over the gold districts.

Gold digs at The Crows’ Nest, St. Mary’s River, Guysborough County, 1897

The second gold rush was considerably tamer than the first, noted more for methodical planning than feverish stampede. Dormant mines reopened in the mid-1880s and mining continued through the 1890s into the early 1900s, thanks in part to geologists and engineers using the latest topographical surveys and mining techniques developed by the Geological Survey of Canada.

It was during the second gold rush that many of the most prominent miners in the province organized the Gold Miners Club of Nova Scotia in 1887, the first professional mining association in Canada.

Despite losing droves of men in 1897 to the Klondike bonanza and newly opened mining camps in Ontario, this period is considered the “golden age” of gold mining in Nova Scotia. From 1885 to 1903, annual yields exceeded 20,000 ounces for 16 of 19 years, with three of those years (1898, 1900, 1901) topping 30,000 ounces.

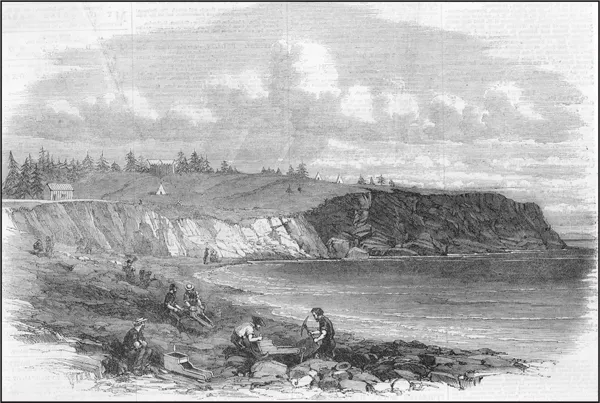

Panning for gold at The Ovens, Lunenburg County, c. 1861

There are several ghost towns from the first two gold rushes for which little documented history remains, but that deserve an honourable mention. Twelve miles from the world-famous fishing town of Lunenburg, near sea caves known as The Ovens, there once was a settlement of 1,000 people where now there is none.

Shortly after gold was discovered there in 1861, Adolphus Gaetz, a Lunenburg dry goods merchant, noted in his diary, “Ovens attracting attention of whole Province … Upwards of six hundred now at work. Shanties erected, grocery shops and restaurants opened … becoming quite a town.…”

Most claims, some of which sold for an inflated $4,800, were concentrated along a beach below the cliffs pictured here. It has been said that shipping magnate Samuel Cunard dredged The Ovens beach for gold and sent boatloads of sand to England for processing.

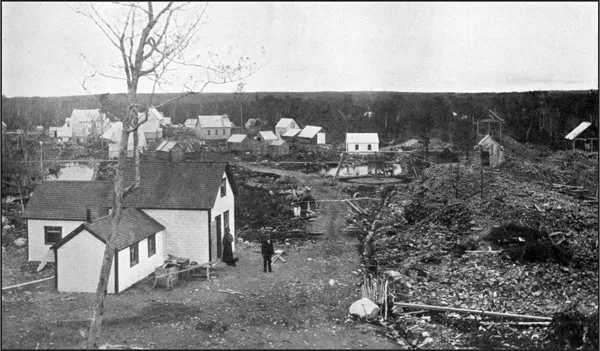

Forest Hill, Guysborough County, 1911

Within three years of Samuel Hudson discovering gold in the backwoods of Guysborough County in 1893, a substantial settlement of houses, stores, a school and three ore-crushing stamp mills had been erected. By 1950, the isolated village known as Forest Hill, that at its height was home to 300 inhabitants, had outlived its usefulness and was deserted.

E.R. Faribault (1855-1934) was the longest serving geologist in the history of the Geological Survey of Canada. Much of his work from 1882 to 1932 was dedicated to exploring and mapping Nova Scotia’s eastern gold districts, including Forest Hill. Fortunately, he also took photographs of gold mining operations and settlements, many of which are used in this book.

Mount Uniacke, Halifax County, 1936

Mount Uniacke and Oldham (opposite) were typical of the quiet, country villages that flourished during the first two gold rushes. The gold districts of Mount Uniacke (1867-1941) and South Uniacke (1888-1948) produced a combined total of 48,498 ounces. By 1867, Mount Uniacke had grown from only two houses to a village of more than 50 and a population of 200 residents. It is shown here in 1936 when J.R. Prince Montreal Mining Co. was in operation. Mount Uniacke today is a developing suburb of Halifax Regional Municipality.

Mount Uniacke, Halifax County, 1936

Village of Oldham, 1890s

Soon after gold was discovered 30 miles from Halifax at Oldham in 1861, there was a church, a school and 30 families. From 1862 to 1946, Oldham produced 85,177 ounces of gold, third highest among the gold districts, with one nugget weighing 61 ounces. At its peak, Oldham had 700 residents. By 1953, there were 75, most commuting to Halifax for work. Today, the “scores and scores of h...