![]()

Chapter 1

Introducing Anglo-Saxon embroidery

This book is about the production and use of embroidery and its relevance in society in the British and Irish archipelagos during the early medieval period, AD 450–1100. It is an interdisciplinary work encompassing study of the design, technique and construction of the embroideries themselves in the archaeological, ecclesiastical and museum contexts in which they are held, and in conjunction with the surviving documentary sources and associated archaeological evidence. By taking an integrated approach and contextualising embroidery within the early medieval period, we can establish its significance as material culture, while at the same time, using it to enhance our understanding of the early medieval world.

Defining the early medieval period

As the medieval archaeologist John Moreland notes, it is not always helpful to compartmentalise eras. Preoccupation with the beginning and end dates of a culture can result in a distorted reading of the evidence, ‘objects, institutions, concepts are treated either as precedent or as relic – not as active in the construction of people and society in their own times’.1 Although the focus of this particular research is the early medieval period in the British and Irish archipelagos and dates have been given as a necessity for confining research parameters, they are intended as a guide to the development of a culture, not in order to isolate embroidery from its own history. Two of the embroideries discussed here, the Orkney hood and the Worcester fragments (remains of what was probably a stole and maniple, worked in silk and silver-gilt threads on a silk ground fabric) (Pl. 1a, b), may date from outside the specified timeframe between c. 250 and 615 and the 11th and 12th centuries respectively, demonstrating that embroidery was, and is, a manifestation of continuity in cultural taste and technical knowledge.

The early medieval period in England is defined as the six centuries from the cessation of central Roman imperial rule in AD 410 to the Norman Conquest of Anglo-Saxon England in 1066.2 Although the people of the territories known today as Wales, Scotland and Ireland did not experience invasion at the hands of the Anglo-Saxons and Normans to the same extent, their history was already entwined with England during this period. Examples include the Scots of Ireland invading and settling in Scotland, and extending their kingdoms into north-west zones of Anglo-Saxon England; the Picts of Scotland raiding the northern Anglo-Saxon kingdoms; and the Welsh incursions into the north-western and western parts of the country. From the 8th century Vikings raided and settled in Ireland as well as eastern England and parts of Scotland, and in the later third of the 11th century the Normans encroached into Wales and Ireland.3

Creative influences, including embroidery, move with people. Design, fashion, materials and working techniques would have spread throughout the countries that make up the archipelagos, moving and morphing as they were encountered by different populations. Indeed, this evolution can be seen in other forms of decorative dress accessory such as metalwork.4 The development and use of embroidery in the different geographical regions is therefore as entwined as the peoples who lived in them. For this reason, embroidery from the regions should be studied as a corpus, not as groups of work that emerged independently of each other. To date, only Elizabeth Coatsworth has treated these works as a single corpus.5

My own study begins during a transitional phase within the archipelagos, with the decline of central Roman influence and the ascendency of Germanic peoples within eastern and southern England. There is still much debate and research regarding this period; but Gildas (d. c. 570?) and Bede (c. 673–735) are usually taken as sources of documentary evidence for the Germanic tribes’ violent over-throw of the native Britons.6 However, Nicholas Higham and Martin Ryan argue that the archaeological evidence does not confirm this, suggesting that the transition occurred over a much longer time-frame, from the early- to mid-5th century, and with little fighting. It would seem that the Germanic peoples’ integration with the local population involved a merging of the two cultures, particularly along the east and southern coasts of modern day England.7

Despite the fact that Bede’s work uses approximations for dates,8 a mixture of convention together with supporting archaeological evidence has led scholars to refer to AD 450 as the beginning of the Anglo-Saxon period in England (and of the early medieval era), and for this reason I have used it as the start date for this survey.9 The rationale for the end date – 1100 – is easier to justify. Although the Norman invasion and conquest of England took place in 1066, scholars now agree that the change was not abrupt.10 Although many of the elite were killed or replaced and church leaders were supplanted by allies of William of Normandy (the Conqueror) (c. 1028–1087), for the rest of society change was more gradual.11 Daily life may have been interrupted, but the shift in material culture took time to evolve. For instance, Norman appreciation of Anglo-Saxon textiles and embroidery is demonstrated by the fact that William’s wife, Matilda (c. 1031–1083) commissioned a cope to be made or embroidered by Aldret of Winchester’s wife and another robe embroidered ‘in England’, both of which she bequeathed to the Church of the Holy Trinity in Caen, ‘Ego Mathildisregina do Sancte Trinitati Cadomi casulam quam apud Wintoniam operator uxor Aldereti et clamidem operatam ex auro que est in camera mea ad cappam faciendam… ac vestimentum quod operator in Anglia …’12 Indeed, Matilda was commissioning people employed in this work prior to 1066.

A surviving embroidery attests to the continuation of Anglo-Saxon material culture beyond 1066: the Bayeux Tapestry, which scholars believe was made in c. 1077 in England.13 It is in part as a result of this textile’s existence that this study concludes after that date, at the end of the reign of William of Normandy’s son, William II (c. 1056–1100). By then, Norman rule was firmly cemented and Anglo-Saxon material culture would have adapted under Norman influence.

Defining embroidery

Defined at face value, embroidery is simply ‘the embellishment of fabrics by means of needle-worked stitches’.14 However there is more to it than this, because embroidery can function in multiple ways at the same time. It can be used to decorate things and create artistic effects and images while also reinforcing and hemming fabrics, darning or joining them. A good example is the Orkney hood, a child’s headdress found in a bog in St Andrew’s Parish, Orkney, which has been radiocarbon dated to between AD 250 and 615.15 The hood, which would have covered the head and shoulders, is made from recycled wool fabric and tablet-woven bands and shows signs of wear in several places. The larger patches have been darned; narrow splits have been joined back together using chain stitch (see Glossary), the edges of the fabric have been whip stitched (see Glossary) and in another area, a tablet-woven band has been attached to the main body of the hood with a complicated variation of looped stitch (see Glossary).16 This single textile demonstrates functional need being accomplished with three different examples of decorative flair, showing that embroidery requires nuanced analysis that takes into account its multiple roles.17

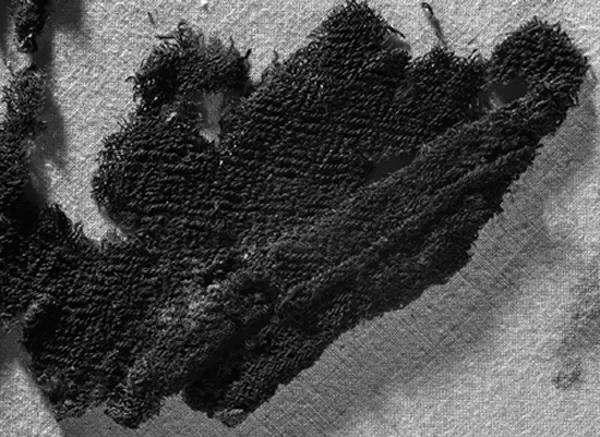

Extant embroideries show that during the early medieval period decoration of textiles took many forms. People used all materials available to them – wool, linen, silk, metal threads and precious stones – to decorate secular clothing, ecclesiastical vestments and soft furnishings. They were innovative in their use of embroidery, using it to decorate and join seams, and mimic more expensive, rarer fabrics. A fragmented textile from Sutton Hoo (known as ‘Sutton Hoo A’) (Pl. 2a), and a small piece of wool embroidery from Kempston (Pl. 2b), illustrate these points well. The Sutton Hoo textile dates to the early 7th century and was probably a pillow or bag. It was constructed from pieces of what was possibly a two-tone fabric cut and sewn together. The surviving seam was constructed using a matching thread. The stitch used to join the two pieces of fabric together was transformed from a plain functional sewing stitch into an elaborate looped stitch that covered the seam while sewing it securely (Fig. 1 and see Glossary). The Kempston fragment (the focus of Chapter 3), which also dates to the 7th century, was worked in fine plied wool threads that looked so similar to silk that they were mistaken for just that until the embroidery was expertly examined in the 1970s by Elisabeth Crowfoot.18

Figure 1. Sutton Hoo A: the seam (measurements: embroidery: 100 × 12–40 mm), © Trustees of the British Museum

People also appear to have used embroidery to symbolic effect. The use of metal threads in ecclesiastical embroideries is a prime example. The effect of the image adorning the garment was enhanced by the way in which the metal threads were manipulated and patterned by the silk couching threads to create areas of light and dark, shine and dullness. The metal threads and silk fabrics would have created a spectacle as the wearer walked through dimly lit buildings. Light from small windows and internal illumination would have been reflected and fractured by the embroideries. As the textiles moved with the wearer they would dazzle the viewer, creating an ethereal image that had the intention of bringing to mind the spiritual. Moreover, the awe inspired by the expense in production time and material costs would have underpinned and cemented the power and authority of the Church, and those who wore and commissioned the vestments.

In this way, embroidery during this period was not just about the decorative and the functional. It became a tool to create, confirm and strengthen power and authority within society and, therefore, an important aspect of early medieval social and material culture. The study of embroidery not only gives a unique insight into fibre and textile production, development of working practices and artistic and technical skills, and the status of workers, patrons and users (especially women); it also provides insight into early medieval mind-sets.

Nearly all scholars of embroidery history cite a very small number of the more famous early medieval pieces before moving rapidly on to ...