![]()

1

Introduction

Chris Scarre

Visitors to the hilltop town of Pavia in southern Portugal are greeted by a curious sight. At one end of the main street, an open square fronts the Igreja Matriz, the principal church; but at the other end another square, with cafes and a small museum, is dominated by a very different religious structure, the anta-capela (‘dolmen-chapel’) of Saõ Dinis or São Dionísio (Figure 1.1). On its eastern side, a rather severe gabled porch with simple round-headed doorway gives access up a couple of steps to the interior of the chapel. Against the back wall, directly opposite, the visitor sees an altar faced with typical blue and white glazed tiles, probably 18th century in date, supporting a statue of the saint himself. The walls of the chapel, however, are not built of conventional masonry but consist of seven massive granite slabs, set upright to support the single stone forming the roof. For this is not an ordinary 17th or 18th-century chapel, but a megalithic tomb transformed into a chapel and taken over for Christian worship.

São Dinis at Pavia is the most striking but by no means the only monument of its kind in western Iberia; some 40 antas-capelas are recorded in Portugal, with further examples in neighbouring regions of Spain (Oliveira et al. 1997). Vergílio Correia gave details of six chambered tombs in and around Pavia, including a smaller tomb, long destroyed, close to the anta-capela (Correia 1921, 26–33). Of these six tombs, only one was converted to Christian usage, chosen no doubt because of its size and its position at the southern edge of the expanding township. Particularly striking in its modern setting, the anta-capela of Pavia and its smaller neighbours serve to indicate the scale and density of Neolithic chambered tombs in this region of western Iberia. The Alto Alentejo is, indeed, one of the areas with the highest numbers of megalithic tombs in western Europe.

The anta-capela of Pavia is typical of these Alentejan tombs in several respects. It is only the chamber of a more complex structure that would originally have included a passage and a covering mound. The chamber is formed of seven granite orthostats, relatively narrow and tall, each sloping slightly inwards and leaning against its neighbour. They support a single capstone. Vergílio Correia recorded over 70 megalithic tombs in the Pavia area and excavated no fewer than 48 of them in three field campaigns in 1914, 1915 and 1918 (Correia 1921; Rocha 1999, 2015a). The excavations were typical for their time, but enabled Correia to draw a number of conclusions, not least concerning the standardised design of the chambers:

Los dólmenes de esta región obedecen a un plan uniforme, constando todos de una cámara más o menos circular, a la cual se entra por una galería o corredor desigualmente extenso. Esta cámara, formada por paralelepípedos irregulares, generalmente en número de siete, que son clavados en el suelo con una cierta inclinación hacia el interior, está cubierta por una piedra mayor, en casi todos los casos circular. Encuéntranse, por excepción, dólmenes cuya sala está formada por piedras en mayor o menor número que los apuntados; pero el número normal, por bien decir ritual, en todas las antas portuguesas es de siete sostenes. (Correia 1921, 66)

[The dolmens of this region follow a uniform plan, all consisting of a more or less circular chamber, which is entered by a gallery or passage of varying length. This chamber is formed of irregular parallel-sided blocks, generally to the number of seven, which are fixed in the ground with a distinct inclination towards the interior, and is covered by a large stone that in almost all cases is circular in shape. Dolmens are found, exceptionally, with a chamber formed of a greater or lesser number of stones than this; but the normal, so to say ritual, number in all Portuguese antas is seven supports. (CS trans.)]

Figure 1.1. The anta-capela of Saõ Dinis at Pavia, Alto Alentejo, a large megalithic chamber converted into a Christian chapel probably at the beginning of the 17th century (Oliveira et al. 1997; Rocha 2015). The interior was excavated in 1914 by Vergílio Correia, who found it had been heavily disturbed although some of the original burial assemblage survived (Correia 1921, 26–31). There is no trace of a mound or cairn today, although excavations in 2013 directly in front of the present entrance uncovered the sockets for two, or possibly three, orthostats from the southern side of the passage (Rocha 2015). (Photo: Chris Scarre)

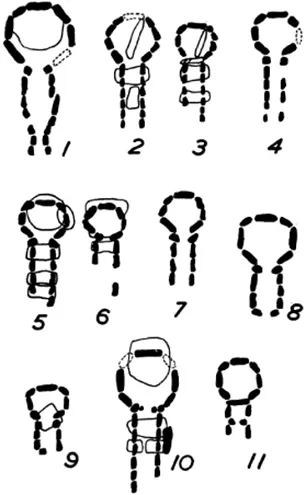

Correia’s fieldwork, though focused on the Pavia area, was not without wider impact on the study of west European megalithic tombs. Glyn Daniel, tracing the origin and development of the passage tombs at a broader geographical scale, drew upon it as a convenient label for all those examples that have a clearly differentiated passage and chamber: ‘The term Pavian Passage Grave is suggested to distinguish the typical Passage Grave from the others, a name taken from the fine concentrations of tombs of this type at Pavia in Portugal’ (Daniel 1941, 3). Using this definition, passage graves in Ireland and northern Europe became variants of the Pavian type. The inwardly-leaning, overlapping orthostats that are so characteristic of many of the Portuguese tombs did not feature in this overarching definition; nor the fact that all 11 of the tombs whose plans Daniel includes have the seven-stone polygonal chamber so typical of the Alto Alentejo (Figure 1.2). This particular configuration is, indeed, restricted to western and northern Iberia.

The anta-capela of Pavia has introduced a number of themes that are relevant not only to the Alto Alentejo region but much more widely across western Iberia. Megalithic chambered tombs – commonly known as antas in Portuguese – are present in large numbers in several other regions, notably in Spanish Extremadura to the east, and in the Spanish province of Galicia in the north-west. Important series of tombs are also known in Portuguese Estremadura, north of Lisbon. Throughout these regions the megalithic chamber consisting of inclined overlapping orthostats supporting a single capstone is the classic (though not the only) type. It is difficult to give an estimate for the total number of surviving tombs, still less for those that once existed, but the number must run into thousands or tens of thousands. Settlement evidence, by contrast, is much more poorly represented, despite targeted field surveys that have been undertaken in several areas in recent decades.

Figure 1.2. Plans of ‘Lusitanian Passage Graves of the Pavian type’. Reproduced by kind permission of The Prehistoric Society from Glyn Daniel, ‘The dual nature of the megalithic colonisation of prehistoric Europe’. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 7 (1941)

That is true for areas immediately north of the River Tagus, which are in many respects an extension of the Alentejan zone. The river, marking the boundary between Alto Alentejo and Beira Baixa, is indeed an arbitrary division. Particularly high densities of tombs are found north of the river in the district of Castelo Branco, and include monuments built of schist and others built of granite blocks. For the latter, as Philine Kalb remarked, ‘os monumentos megalíticos de Castelo Branco pertencem à zona megalítica alentejana, separados desta apenas pelo rio Tejo’ [the megalithic monuments of Castelo Branco belong to the Alentejo megalithic zone, separated only by the Tagus River] (Kalb 1987, 96). This observation has a particular salience in the current volume since it was north of the river at the Anta da Lajinha, on the western edge of the Castelo Branco megalithic cluster, that the fieldwork was conducted that is reported in Chapter 2.

The regional clusters of megalithic tombs form a series of megalithic landscapes, in which tombs are the most conspicuous surviving element. The high densities pose a number of questions about the nature of the Neolithic societies who constructed them and the circumstances in which they came to be built. At the most general level, they form part of the broader family of Neolithic chambered tombs and related monuments that extends from Poland in the north-east to the Straits of Gibraltar in the south, and beyond that into North Africa. That said, regional identities and regional traditions are paramount in understanding the relationship of megalithic tombs to the individual communities who built and used them. Furthermore, tombs are grouped morphologically and chronologically and offer characteristic regional types that imply a strong regional component to their design and meaning, and to the funerary and other practices that were performed there. The concept of the chambered tomb and the valency of megalithic slabs may have been widely shared between different regions of Atlantic Europe. Other features, such as the common provision of a passage, designed perhaps to permit repeated or permanent access, and the practice of above-ground burial within these chambers, also denotes shared beliefs and customs. Once one moves beyond that very general level of analysis, however, regional differences become as salient as the interregional similarities. The typical seven-stone chamber is not a recurrent feature of any region of Europe outside northern and western Iberia. Nor are characteristic associated artefacts such as the engraved stone plaques and crooks (báculos) found beyond Portugal and south-west Spain (albeit the latter resemble motifs found in megalithic art, both in western Iberia and in north-west France: Calado 2002; Cassen 2012). This makes the interpretation and understanding of the patterning at both regional and interregional scales particularly challenging.

Chambered tombs are not the only phenomenon that implies Neolithic movement along the western seaways. There is increasing evidence for the transport of raw materials such as variscite, jadeitite and eclogite (Herbaut and Querré 2004; Querré et al. 2014; Odriozola et al. 2016; Pétrequin et al. 2012b, 2017). Furthermore, the Atlantic distribution of megalithic monuments overlaps (both in time and space) with the distribution of another significant phenomenon: rock art. The recognition of postglacial rock art as an Atlantic European phenomenon arose from the discovery of parallels between rock and megalithic art in Ireland, and their resemblance to motifs from Galicia. The abbé Breuil noted the connection in his presidential address to the Prehistoric Society of East Anglia in 1934, and he returned to the theme a quarter of a century later when he drew the megalithic art of Brittany into the same framework (Breuil 1934; Breuil and Boyle 1959). The parallels were studied in detail by Eoin MacWhite, who was sent by Gordon Childe to work with Iberian colleagues in Madrid (Díaz-Andreu 1997, 23; Bradley 1997, 37). MacWhite distinguished in the Irish context between ‘Galician’ art (i.e. rock art in which cup-and-ring motifs form a major component) and Irish passage grave art. The ‘Galician’ tradition was ‘derived, ultimately perhaps from the East Mediterranean, but immediately from the north-western part of the Iberian Peninsula, where it appears to be mixed with epi-Palaeolithic survivals’; whereas passage grave art ‘came from the Southwest of the Iberian peninsula’ although it too ‘has its roots in the East Mediterranean’ (MacWhite 1946, 75). As Bradley has noted, the motifs of Irish megalithic art are entirely different from those of Britain and Brittany. There are considerable differences between Galician and Irish rock art, with most Irish motifs also found in Galicia, whereas Galician art contains animal and other motifs not found elsewhere. Nevertheless, Bradley observes that even though the motifs are not identical between the two regions, broad similarities in the integration of elements support the sense of an underlying Atlantic rock art (Bradley 1997, 41). The pattern, and the problem, is in many respects similar to that for the megalithic tombs: a general interregional distribution within which regional variability is particularly striking.

Rock art in western Iberia overlaps in distribution with major clusters of megalithic tombs, and some have drawn a direct connection between the two in terms of the structuring of the landscape (Fairén-Jiménez 2015). That is true, for example, in the Tagus Valley, where the principal areas of rock art are contiguous to regions north and south of the river that have an unusual abundance of megalithic tombs. It has been suggested that at least some of the Tagus rock art may have been created by the builders of the tombs, although there are issues of chronological resolution to be considered (Serrão et al. 1972a; Oliveira 2008a, 2008b). The relationship is explored in Chapter 5. Another line of analysis points to close links between rock art and Iberian megalithic art, arguing that they are overlapping elements of a single symbolic system (Bueno Ramírez and Balbín Behrmann 2002; Bueno Ramírez et al. 2014). In Galicia, a specific spatial relationship between megalithic tombs and cup-marks has been observed (Criado Boado and Villoch Vázquez 2000, 201). More generally, parallels have been drawn both with the Atlantic rock art of Galicia and northern Portugal (sometimes called ‘Galician-Atlantic’) and with the more widely distributed Schematic Art. Galician Atlantic rock art is exclusively carved, whereas Schematic Art includes both carved and painted motifs. There are changes through time in both the motifs and the location of the art: Galician Atlantic rock art consists of geometric motifs, whereas in later periods weapons and humans and animals (notably stags) are represented. Schematic Art too extends beyond the Neolithic into the Bronze Age, and whereas Galician Atlantic rock art is generally in more open and accessible locations, Schematic Art is also found in rock shelters and caves (Fairén-Jiménez 2015). The long development of the Tagus Valley rock art includes a phase with Schematic Art motifs that may be contemporary with the megalithic tombs (Gomes 2007; Baptista 2009; Garcês 2018; see also Chapter 5 below). Its location, among the litter of angular, irregular schist blocks that fringe the river either side of the Portas do Rodão, presents the difficulty of access typical of Schematic Art (Figure 1.3).

The rock art traditions of Neolithic and Chalcolithic Iberia are just one part of a wider range of symbolic material culture that includes iconic and aniconic artefacts of stone, bone and ivory, and occasionally gold. This sets southern Iberia apart within Western Europe as a whole (Scarre 2017). The most abundant category is the engraved stone plaques of south-west Spain and southern Portugal (mainly of slate, although often referred to as schist); a recent estimate suggests that as many as 4000 of these may survive in museum or private collections (Lillios 2008, 17). Most of them come from chambered tombs, either of megalithic construction, or of the later ‘tholos’ or rock-cut varieties.

There is clearly a risk here of conflating time. The chronologies of Galician Atlantic rock art, Schematic Art, and megalithic tombs may overlap, but the geographical distribution we see today is a palimpsest of individual actions spread out across several generations. It poses key questions about duration and memory. Tombs once built, rocks once carved, endure for long periods. Many tombs had been subject to re-use in the Beaker period or the Bronze Age, testifying to their continuing visibility and significance. Some had been remodelled and their inner surfaces repainted or recarved. Yet as far as the tombs are concerned the construction period itself may have been relatively short.

Although precise chronologies are difficult to achieve, iconographic complexity appears to be a feature of the later Neolithic and Chalcolithic in southern Iberia, and where decorated stone plaques or limestone ‘idols’ are found in classic Portuguese antas, in the majority of cases they testify to re-use during the late 4th or 3rd millennium BC. The tombs themselves could be considerably earlier in date. Many of the available radiocarbon dates on human remains from the tombs fall in the late 4th millennium BC, but some may have been built during the first half of the 4th millennium, perhaps even beginning in the late 5th mil...