eBook - ePub

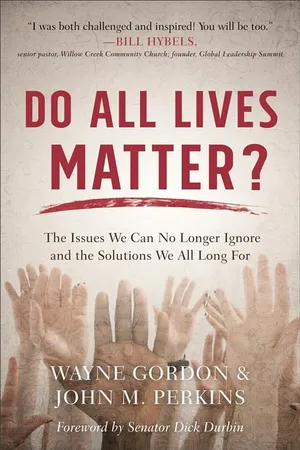

Do All Lives Matter?

The Issues We Can No Longer Ignore and the Solutions We All Long For

- 96 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Do All Lives Matter?

The Issues We Can No Longer Ignore and the Solutions We All Long For

About this book

Something is wrong in our society. Deeply wrong.

The belief that all lives matter is at the heart of our founding documents--but we must admit that this conviction has never truly reflected reality in America. Movements such as Black Lives Matter have arisen in response to recent displays of violence and mistreatment, and some of us defensively answer back, "All lives matter." But do they? Really?

This book is an exploration of that question. It delves into history and current events, into Christian teaching and personal stories, in order to start a conversation about the way forward. Its raw but hopeful words will help move us from apathy to empathy and from empathy to action.

We cannot do everything. But we can each do something.

The belief that all lives matter is at the heart of our founding documents--but we must admit that this conviction has never truly reflected reality in America. Movements such as Black Lives Matter have arisen in response to recent displays of violence and mistreatment, and some of us defensively answer back, "All lives matter." But do they? Really?

This book is an exploration of that question. It delves into history and current events, into Christian teaching and personal stories, in order to start a conversation about the way forward. Its raw but hopeful words will help move us from apathy to empathy and from empathy to action.

We cannot do everything. But we can each do something.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Do All Lives Matter? by Wayne Gordon,John M. Perkins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A Movement Is Born

Do all lives matter? On the surface, the answer seems obvious. Of course all lives matter! This conviction lies at the core of America’s identity and has since our nation’s beginning. The Declaration of Independence states, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights.”

The affirmation that all lives matter is consistent also with Christian faith and core theology. All human beings are created in the image of God, and the Scriptures could not be more clear that all are equal in God’s eyes.

What we must recognize, however, is that the concept of all people being equal—and all lives mattering equally—exists as an aspiration, not as a reality. To put it another way: it exists in theory but has never existed in practice. After all, many of the men who signed the Declaration of Independence owned slaves. And the document they signed specified equal rights only for one gender. We can either call the Declaration’s signers hypocrites or credit them for holding up an ideal for the nation to pursue.

Of course, much has changed in the nearly two and a half centuries since that Declaration was signed. Slavery ended more than 150 years ago. Today, women not only can vote but can hold any political office. Yet if we are to be honest, we must acknowledge that in 2016 people are still routinely treated unequally—both legally and socially—based on factors ranging from how much money they make to social status and family pedigree to ethnicity and skin color to physical ability or disability to height and weight and how good-looking they are. Does anyone really think that television weatherpersons got the job based on how well they did in their college meteorology courses?

Determining how fair things are for individuals or groups can be complicated. After all, it’s possible for the same people to be discriminated against in some settings while being favored in others. For example, it’s well documented that an African American male is more likely to be treated unfairly by our justice system than a Caucasian person. But when applying for a job, that same African American male might get preferential treatment from an employer committed to hiring minorities, even if he grew up with more social and financial advantages than his white counterpart.

Because there are so many angles from which to analyze particular cases of alleged injustice—and different criteria for determining what is fair and right—it can be challenging to reach definitive conclusions. But the complexity should not prevent us from recognizing trends and realities that are difficult, if not impossible, to deny. It should not, for example, stop us from asking why—more than 150 years after the demise of slavery and several decades removed from the Civil Rights revolution—so many African American people in our country feel the need for the movement “Black Lives Matter.”

Consider that many African American people would testify that there has never been a time when they haven’t been mistreated by law enforcement. Modern technology, including cell phone videos, has only brought the issue more squarely into the public eye.

The highly publicized 2012 killing of Trayvon Martin in Sanford, Florida, was a turning point, one that gave birth to the term “Black Lives Matter” and to organized protests calling for justice. A vigilante named George Zimmerman shot and killed Martin, a teenage boy, while he was walking home from a store. Of course we know how this story ended. Zimmerman’s acquittal spawned outcries from African American communities across the country.

In July 2014, forty-three-year-old Eric Garner was stopped by New York City police for selling loose cigarettes. He was wrestled to the ground as a police officer put his head in a chokehold. The incident was captured on video. Garner can be heard saying “I can’t breathe” eleven times. The New York medical examiner officially ruled this case a homicide. But in December 2014, a grand jury decided not to indict the officer, sending the message to African Americans across this land that their lives do not matter.

After Michael Brown was shot and killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, on August 9, 2014, “Black Lives Matter” evolved from slogan to movement. Brown, though unarmed, was killed by Darren Wilson apparently for stealing a few dollars’ worth of merchandise. The movement added the slogan, “Hands up, don’t shoot.”

There are many more cases, but these three alone establish that being black in America can be difficult and dangerous. Each of these three persons received a death sentence for walking home, selling cigarettes, or minor theft. The effect of their experiences has gone far beyond their grieving families. It has sounded a chord that resonates deep in the lives of African Americans and many others as well. These incidents have launched a dialogue on the topic of whether—and to what extent—black lives matter in the United States of America. The Black Lives Matter movement has given hope to many African Americans who have often been told in different ways that their lives don’t matter—that, despite our country’s highest aspirations, they are not equal in the eyes of others.

Our country’s racial divide is evidenced in part by how some have responded to the Black Lives Matter movement, specifically those who have countered with the slogan, “All Lives Matter.” As noted at the beginning of this chapter, no good person can dispute the affirmation that all lives matter. In American culture, it ought to be, as the Declaration’s signers put it, “self-evident.” But the use of the slogan as a response to Black Lives Matter dilutes the meaning and significance of the Black Lives Matter movement. It does so by suggesting there is no need for a movement or dialogue focused specifically on the challenges African American people face in our country. This subtly suggests that black people are treated the same as everyone else.

So why the protests?

Why the complaining?

Their situation is no different from anyone else’s, so why the need for a movement?

Simply stated: All lives can’t matter until black lives matter.

Our opposition to the clearly implied message of the “All Lives Matter” response is simply, “True, all lives matter, but we have to wake up to the reality that our country remains divided over issues related to race. We have to own up to the fact that African Americans and other ethnic minorities in our country are mistreated far more often than most of us care to admit. Along with this, we must acknowledge that not all the problems minority groups face are the result of white racism and that some have been too quick to cite racism as the sole cause of their struggles, thus avoiding or downplaying the role of personal responsibility.”

Where does all this take us? It gets us on the journey of treating all people like their lives matter. It takes us to a place in which we all have a lot to learn. A place that demands we listen more carefully to the experiences, perspectives, and feelings of others. A place we need to approach with humility and an openness to change. For some, this might be an unfamiliar place; for others not so much. But it’s a place where we all need to be if we want to change things for the better.

No book has all the answers; certainly this one doesn’t. It’s only a start. This is not an easy journey but it is an important one. We invite you to come along.

2

Listening to Others’ Stories and Sharing Our Own

One of the most important messages of this book is that if we are going to make progress with regard to behaving as if all lives matter, we need to make a genuine effort to understand others and the realities and struggles they face. The challenge is to go beyond knowing another person’s reality to feeling it to the full extent that we can. We do this by listening to their stories and by sharing our own. I (John) encourage you to do this with as many others as you can.

Following is a summary of my story, along with my perspectives on some of the issues our country is facing with regard to the topic at hand.

At this writing, I am eighty-six years old. I’ve lived a life full of both intense sorrow and struggle as well as great happiness and joy. And I’m not done yet. At eighty-six, I know that I have been created in the image of God. And I know that my life matters. In fact, I know now that my life has always mattered. But I have not always felt that it did.

My earliest memories are of running around in a house full of aunts and cousins. When I cried out, “Mama, Mama,” my cousins told me my mother was dead. So from my earliest days, I was aware that I did not have a mother. I would later learn that she died when I was just seven months old. She died in poverty, essentially of malnutrition. She was still breastfeeding me at the time of her death. I’ve often felt that I took the energy and nutrition she needed to survive. I don’t know for sure if that is true, but I do know that she died and I lived.

I understood that I didn’t have a family—an institution of affirmation and support. I didn’t have a mother to love me and there was a leaky hole in my heart. As a child, I never really quite got that hole filled. I could have been angry and bitter. I could have been hardened to the point where I felt that my life didn’t matter and that I could just kill myself. I could have decided that no one else’s life mattered either.

Acts of kindness, like the lady from up the street who brought a quart of fresh milk to my grandmother’s house for me every morning, helped affirm me as a person. My life mattered to her.

My father was still alive but he had married someone else. He and his wife lived about fifty miles away and had no children. It seemed to me that she probably liked it that way. They lived in what would be considered slaves’ quarters—a one-room house behind a plantation-style home. Some of these houses can still be found today in New Hebron, where I grew up.

My father and I had a strange kind of relationship. From time to time, I would visit him and his wife, and he also would visit me at my grandmother’s, usually coming alone. When I was seven years old, my grandmother and I went to visit him and in the afternoon my father and I went to buy some food for the next morning. I already knew how to write my name. So, when we went into the little grocery store to get some food and my father signed his name with an X, I was shocked.

Sometimes people who grow up with certain disadvantages in life blame other people, including their parents. But I could not blame my mother for dying when I was a baby, nor could I point a finger at my father for not knowing how to read or write. I sensed early on that I had to take responsibility for my own life.

A Lesson Learned Hauling Hay

When I was about twelve years old, I was away from home with a friend for a little summer getaway. We needed to find some work in order to make a little money so we could prove to the kids back home that we’d been away on vacation. It wasn’t too hard for young people to find work because this was during World War II; a lot of the men had gone away to war. My friend and I landed a job hauling hay for a white gentleman. We knew that the going rate for a whole day of hauling hay was at least a dollar, maybe as much as a dollar and a half. We worked hard all day and then went in to get paid. Because we were black, we had to go in through the kitchen to collect our pay. I still remember how disappointed and angry I was when the gentleman handed each of us a dime and a buffalo nickel.

I was so upset that I didn’t even want to take the money. I wanted to throw it on the ground because I knew the time and energy I’d put forth that day was worth far more than 15 cents. And my dignity was also worth more than that 15 cents. But despite all that, I took the money. I knew that back in those days, had I not accepted it I would have been considered a “smart, uppity nigger.” The people who were raising me would have been accused of tolerating a “little smart nigger boy” who rebelled against white folk.

This incident ended up being a turning point in my life. I took responsibility for getting myself into the situation of working for that man that day. It started me to thinking: this man had the mule and he had the wagon. He had the hay and he had the field and he had the means of production. He had the capital—and I could see, even as a young boy, that the person who controlled the capital made all the decisions.

Instead of becoming bitter, I came to understand that I had value. I would take responsibility for myself and my work. I had to find a way to get the mule, the wagon, the hay, and the field. I had to take the initiative to develop whatever skills and abilities were needed to produce some combination of goods and services to improve my station in life. From that point on, I didn’t wait around for anybody to offer me a job. I took the lead and I became a businessman. I wanted to contribute something of value and I wanted to learn. And I made it my responsibility to do both.

I believe that people are often pierced to the soul by how others treat them. We have to create an environment where the soul can be satisfied, or at least soothed, in its longing to be perceived as meaningful. Others in our lives balance our perspectives. When our souls cry out for significance, the pain has to be resolved.

Third-Grade Education

Because we were sharecroppers, we learned to work the fields. That was the focus; our ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Endorsements

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- 1. A Movement Is Born

- 2. Listening to Others’ Stories and Sharing Our Own

- 3. Owning Up

- 4. Invisible People

- 5. Building on Common Ground

- 6. Black Lives Matter

- 7. From Tears to Action

- 8. Let Us Sow Love

- 9. Holding On to Hope

- Afterword

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- Back Ads

- Back Cover