- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

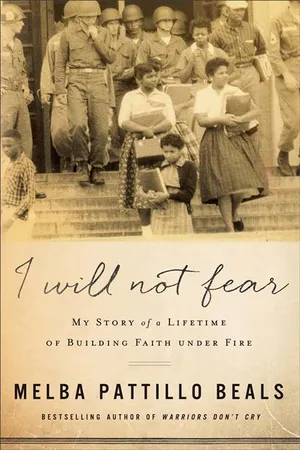

About this book

In 1957, Melba Beals was one of the nine African American students chosen to integrate Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas. But her story of overcoming didn't start--or end--there. While her white schoolmates were planning their senior prom, Melba was facing the business end of a double-barreled shotgun, being threatened with lynching by rope-carrying tormentors, and learning how to outrun white supremacists who were ready to kill her rather than sit beside her in a classroom. Only her faith in God sustained her during her darkest days and helped her become a civil rights warrior, an NBC television news reporter, a magazine writer, a professor, a wife, and a mother.

In I Will Not Fear, Beals takes readers on an unforgettable journey through terror, oppression, and persecution, highlighting the kind of faith needed to survive in a world full of heartbreak and anger. She shows how the deep faith we develop during our most difficult moments is the kind of faith that can change our families, our communities, and even the world. Encouraging and inspiring, Beals's story offers readers hope that faith is the solution to the pervasive hopelessness of our current culture.

In I Will Not Fear, Beals takes readers on an unforgettable journey through terror, oppression, and persecution, highlighting the kind of faith needed to survive in a world full of heartbreak and anger. She shows how the deep faith we develop during our most difficult moments is the kind of faith that can change our families, our communities, and even the world. Encouraging and inspiring, Beals's story offers readers hope that faith is the solution to the pervasive hopelessness of our current culture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access I Will Not Fear by Melba Pattillo Beals in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Théologie et religion & Biographies de sciences sociales. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

One

An Angel with a Broom

December days in Little Rock, Arkansas, are filled with a foggy ground chill that bites the bones, no matter how many coats and hats one wears. On December 1, 1941, my grandmother, India Peyton, was midway on a twelve-block walk to downtown in order to see a supervisor at Missouri Pacific Hospital. She was seeking permission for my mother to be given space in the maternity section because Mother Lois was about to give birth to me. Grandma worried that the bulge of my weight in her daughter’s stomach far outweighed her capacity to birth me.

“White folks don’t take kindly to the notion that one of us might be in their hospital. But because Daddy Howell was a worker there, there was some hope we could get your mother in. Your mother’s belly was stretched bigger than God planned it to be,” Grandma would later tell me.

Mother Lois was five feet four and weighed ninety-three pounds. Doctors estimated that I could weigh at least nine pounds. Grandmother had already been told that she would not be allowed to bring her daughter to the hospital, no matter the risk.

The previous morning, Grandmother India had been turned down again by the clerk. She requested to see a higher-ranking supervisor to plead for entry for Mom. Now a little more than halfway there, walking as fast as she could, she wondered whether she would ever get there. The fierce wind bit her legs and seared her cheeks. She felt as though it would knock her down. If she could have made the trip a little later, she could have ridden the bus. But at 5:30 in the morning, no buses were running. She could not risk being even a moment late for her 7:00 a.m. job as a maid at the hotel.

Protecting her face with her gloved hands, she tried hard to see what was in front of her. Grandmother decided that the only way she was going to complete her trip was to pray aloud the familiar Lord’s Prayer. Upon arrival at the back door, the entry assigned to people of color, she wondered whether she had the strength to swing the heavy double doors with the strong wind blowing. Just then the door swung open for her, and Mr. Jeffers, the janitor, reached his hand out to her and pulled her inside to the warmth.

“Miss India, what on earth is a body doing out here in all this freezing weather?”

Taking off her glasses to clear the fog, she asked Mr. Jeffers to point her to Mr. Van Albor’s office.

“Ohhh, Miss India, why you looking for him? He ain’t gonna see nobody like us.”

“I need to get doctoring for my baby. She’s with child, and I want her to come here because the baby is really big. That baby weighs too much for her little body to carry.”

“Oh Lord, you know they ain’t gonna let that happen. The saying here is, if you let one in, they’ll all think they’re entitled to be here.”

“I got no choice, Mr. Jeffers. I gotta save my baby’s life.”

She turned and walked toward the elevator, following his directions. On the third floor, there stood the huge wooden door that led to the hospital supervisor’s office.

“I need Your help, dear Lord.” She hesitated a moment to whisper her prayer before she knocked for permission to enter.

“Good morning, Aintee. I understand you want me to do the impossible.”

“No, sir. I want you to please help me save my daughter’s life. My son-in-law, Howell Pattillo, is a good man and is one of your workers here. He is a Hostler’s helper on the Missouri Pacific Railroad.”

“You’re not asking for special treatment, are you? You know very well that Negras aren’t coddled here.”

Grandma winced because he used the familiar word Negra, which racist white folks called a compromise—a combination between nigger and Negro. She grasped control of herself as she squeezed her feeling tight in her throat. She could ill afford to offend him at this point.

“No, sir, of course not.”

“The answer is no, Aintee. Why are you wasting my time?”

Grandma says her heart sank as she moved toward the door, and then she remembered what her pastor had instructed.

“Bishop Riley said I should ask because it is so important to save my daughter’s life. She’s a schoolteacher and a Christian. We and Bishop Riley would be grateful.”

Grandmother’s pastor had advised that the only possible way to get her daughter into the hospital was if Bishop Riley supported her. He was the only African American in our community who held sway over some members of the white community. Nobody seemed to know why, but everybody in our community knew it was just so.

“Aintee, now you know that there’s no way I can give you a regular room. I’ll allow her to stay here in a storage room. We have an empty room. So it’s yours while it’s empty. She needs to have that baby before a week passes. Do you hear me? A week.”

“Oh, thank you, sir, thank you. I will report your kindness to the bishop.”

“Hold on, Aintee. Don’t get any ideas about inviting your relatives and friends to celebrate. Only you, the father, and the mother can come in that back door, and be quiet. Nobody needs to know you all are here.”

“Yes, sir.”

“And there will be no birth certificate saying that baby was born here. I don’t want a parade of Negras marching here stinking up the place.”

“Of course, sir.”

Backing out of the office, curtseying with her hands in a praying position, Grandmother was very grateful.

On Saturday afternoon, December 6, Mother Lois began harsh, prolonged contractions and spurts of pain that overcame her. Papa dropped her and Grandma off just outside the hospital back door. Mother was in a small, windowless but clean room. She began what would become a long night and next day filled with drama and pain with Grandmother at her side. The room Mother occupied was down an isolated hallway. When Grandmother asked for pain medication, the nurse said, “Give you niggers an inch and you take a mile.”

Early the next morning, Mother was wrenched with pain and covered with perspiration. Grandmother feared that nurses and doctors would ignore her. She telephoned Dr. Routen, a white doctor who had been our family doctor for several years. He came to the hospital and summoned another physician to give Mother medicine and take her to the delivery room.

Meanwhile, Dad discovered a radio down the hall and was busy going back and forth between the two rooms as he announced, “Pearl Harbor has been attacked.”

December 7, 1941, was a traumatic day that looms in this country’s history! Bombs were bursting in air as Pearl Harbor was shattered. Hearing announcements of this tragic event was secondary in Mother’s life as she prepared to give birth to her first child.

Grandmother prayed and read Bible verses as Father meandered back and forth with news of Pearl Harbor. They anticipated a difficult birth. It lasted thirty hours. Mother Lois was petite—while Father was six feet four and two hundred pounds. As time grew near, Grandmother reported that there were signs of trouble. Dad was not called, as men were not allowed in the delivery room.

When the birth process grew ever more difficult, the doctor decided to use forceps, though admitting this practice could lead to infection. I weighed nine pounds, eight ounces.

After the birth was complete, Mom and I were taken to the storage room. On the way out, Grandma remembered seeing Mr. Jeffers cleaning the birth room.

By my first evening on earth, December 7, it was evident that my head was swelling, and I could not keep my tiny hands from scratching. Grandma said I cried all night long, but even though she pled with the nurse, no one would come to address my problem. By Monday, my temperature had soared to 103 degrees. My hot, swollen head was an open, bleeding wound, which alarmed Mother, Grandmother, and Father.

By Tuesday, December 9, my temperature was 105. The doctor announced that the infection was spreading, and I probably would not make it. He operated on my head and inserted irrigating tubes.

The next day, just outside Mother’s door, Mr. Jeffers was sweeping the floor. When he heard Grandmother praying aloud as Mother cried softly, he stepped inside the door and expressed his concern. “I guess washing her head with that there Epsom salts did not work,” he lamented.

“What Epsom salts?” Grandmother asked.

“The doctor told the nurse the baby’s head needs rinsing every two hours or so with Epsom salts.”

“No,” Grandmother said, “the baby’s been here with us, and the nurse has not come to rinse her head.”

Racing down the hallway, Grandma got ahold of the nurse. “We do not coddle niggers here,” the red-haired nurse shouted. “Understand I don’t have time for you or your baby. You don’t belong here!”

Grandmother grabbed her purse and left for the store to purchase Epsom salts. Only by the grace of God and an angel carrying a broom did I live. Three days later, we left the hospital.

As a child growing up, I always fretted about the bald strip that ran from the top of my misshapen head down to the right ear. I was so afraid that one of my friends would say something. Grandmother always quieted my fretting—explaining that it was proof of how special I was in God’s eyes because He had saved my life against all odds. “God has been kind to give you beautiful hair like shiny black satin to cover your scar. No one will know,” she said. “God has rescued you from death because He has special assignments for you. You will get word of the tasks you are to perform when He deems you ready for His work.”

That special assignment came fifteen years later in September of 1957, when I was chosen as one of the Little Rock Nine—nine African American children selected by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) to integrate Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, amid a firestorm of angry mobs determined to keep us out.

It was not until fifty years later that I learned the enormity of the blessing I was granted. A cranial specialist was to examine my head because I had felt some discomfort after I accidently caught my head when closing the car trunk. As the nurse entered the room to gather preliminary information, I greeted her. She examined my head and began talking loudly and slowly to me as though I was hard of hearing and mentally disabled.

“What day is it?” she shouted, leaning in close, staring at me.

“Tuesday,” I said, curious about her behavior.

“Who is president?” she screeched.

“President Clinton, William Jefferson Clinton,” I repeated.

At first, I cooperated with her line of questions, but then I screamed, “Lady, I am a professor with a doctoral degree. How can I help you?”

That is when, with an astonished expression, she explained to me that with my misshapen head and the nature of the injury, I could have suffered cerebral palsy or another severe brain injury. The doctor said I was a walking miracle. I whispered, “Thank You, God,” all the way back to the car.

What I know for sure is that we have a God who guides and protects us. God is always available when we call for help and even when we are unable or unwilling to call. He intervenes to rescue us, even when we don’t know we need help.

Two

Walking through the Valley

Growing up in segregated Little Rock, Arkansas, in the 1950s was a deep life and faith struggle for a person of color. The first emotion I was aware of was fear. Fear of what would happen if we disobeyed the rules connected to large signs placed everywhere that read Whites Only, Black Folks Not Welcome. By the age of three, I noticed that white people were in charge, because they were the ones who kept telling the grown-ups in my family what to do. Every time we encountered them, my mom, dad, and grandma behaved as though they were really nervous and frightened they might do something wrong. Their fears were contagious because I mimicked that fear as well. Whenever we were near white people or even any of our relatives who were white-skinned and blue-eyed, I was terrified. So much so that when my blue-eyed cousins came to babysit us, I hid in the closet or under the bed.

At age five, I joined in with the adults and complained about white folks being in charge because I resented not being able to ride the merry-go-round, sit in movies, or swim in the city pools. “Why can’t God make them share?” I asked over and over again. “We could each be in charge half a year. Put them in charge from January to June and give my folks charge from July to December.”

“In God’s time,” Grandma replied. “Be patient. God loves you. Trust and He will provide.”

Following the 1954 decision by the US Supreme Court that separate is not equal and that all public schools must be open to all children, the NAACP demanded that Arkansas’s formerly all-white schools comply. Little Rock school officials announced that they would comply with the court order by choosing African American children to enter the all-white Central High. I was selected as one of the first nine teenagers to enter that prestigious white school, which had a student body of more than nineteen hundred.

Suddenly, in early September 1957, the city that had been my home for most of my life turned into an armed camp with hundreds of folks gathering in front of Central High each morning with the intent of keeping the nine of us out. After a few days, the press was describing this gathering as a mob—a rampaging, out-of-control mob. News reporters from around the world were arriving in my hometown, focusing on what was becoming a volatile battle between our US government and the state of Arkansas, and I was in the middle of it.

At the tender age of fifteen, my struggles to share equal opportunities would become a primer for my understanding of faith. Being able to sustain myself through a school year fraught with drama, violence, and fear was a critical tool in faith building. Integrating Central High School would become the foundation for a lifetime of sustaining faith and trust. That experience enabled me to embark upon a journey of life’s challenges with the confidence that Jesus would always be at my side.

A shouting, angry, rock-throwing mob continued to block the entryway to Central High School during early September and the beginning of classes. As always, the Ku Klux Klan rode at night, only now more frequently in our neighborhood, violently threatening random people from our community because we wanted to attend their school. Unfortunately, news reports listed our addresses and phone numbers. I began receiving threatening and vulgar phone calls day and night. Shots rang out, and bullets pierced our window, shattering Grandmother’s antique flower vase, which stood on top of our television.

Due to the escalating violence, I was no longer a cheerful teenager enjoying the Saturday night Hit Parade of music on television or waiting to hear Johnny Mathis sing on the radio or gathering at our community center to chat, play games, or take dance lessons. Instead, I was forbidden to leave the house without appropriate adult escorts. The only time I saw other teenagers was at church. My social life was crammed with press conferences and official meetings with the eight others who shared my predicament. These integration strategy meetings and lectures from Arkansas school officials were to tell us what we could and could not do—for example, “Don’t antagonize w...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. An Angel with a Broom

- 2. Walking through the Valley

- 3. Angels in Combat Boots

- 4. Through Trials and Tribulations

- 5. Finding My Inner Warrior

- 6. Keeping My Faith in My Darkest Hour

- 7. God Is Everywhere, Especially in California

- 8. I Didn’t Expect It to Happen This Way

- 9. Single Parenthood

- 10. Don’t Let Anyone Steal Your Dreams

- 11. God Grants Dreams Bigger Than You Imagine

- 12. Turning the Other Cheek

- 13. God Is My Employer

- 14. Serving Others and Serving God

- 15. God Meets Our Needs in Unexpected Ways

- 16. Age Is Just a Number

- 17. God Is as Close to You as Your Skin

- 18. Our Nightmare Dream House

- 19. Terror Times Two

- 20. Where There Is Faith, There Is Hope, Forgiveness, and Gratitude

- Epilogue

- About the Author

- Back Ads

- Back Cover