- 124 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This helpful book offers a simple and commonsense introduction to the care of patients in the generalist setting for whom a palliative approach is deemed appropriate. Many of these patients may be living at home or in care homes, and many may be months or even years away from the terminal phase of illness. With the aid of reallife examples and case studies, this text aims to give a wide range of healthcare professionals an understanding of, and competence in, the provision of holistic, supportive care that is focused on comfort and quality of life.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Palliative Approach by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicina & Anestesiologia e gestione del dolore. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

What is palliative care?

No area of medicine has received as much attention as palliative care – in the sense of workshops conducted and articles written. Work still continues on finding the best name for this type of care, with various services around the globe using terms such as ‘hospice care’ and ‘supportive care’ among others.

The fact that palliative care cannot be defined by an organ (unlike cardiology or nephrology), by the chronology of a specific disease, or by the geographic boundary of a single patient, creates the need for a complex definition. Even the World Health Organisation (WHO) had trouble, and the wording they ended up with hints at consensus by a big panel!

The current WHO definition of ‘palliative care’ is (www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/):

an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual.

Palliative care:

• Provides relief from pain and other distressing symptoms;

• Affirms life and regards dying as a normal process;

• Intends neither to hasten or postpone death;

• Integrates the psychological and spiritual aspects of patient care;

• Offers a support system to help patients live as actively as possible until death;

• Offers a support system to help the family cope during the patient’s illness and in their own bereavement;

• Uses a team approach to address the needs of patients and their families, including bereavement counselling, if indicated;

• Will enhance quality of life, and may also positively influence the course of illness;

• Is applicable early in the course of illness, in conjunction with other therapies that are intended to prolong life, such as chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and includes those investigations needed to better understand and manage distressing clinical complications.

No other medical specialty has such a long definition and certainly no other requires multiple bullet points! It is difficult to avoid the feeling that palliative medicine is still desperate to ensure that it is taken seriously.

The cumbersome WHO definition has led many units and services to develop their own, simpler version. The definition used by the unit in which I practise is:

Palliative care is the integrated and multidisciplinary assessment, management, support and care of patients, their families and carers, who are living with active, progressive and far-advanced disease for whom cure is no longer an option, prognosis is limited, and where quality of life is the central concern. Palliative care is holistic, patient-focused care and support is continued into the bereavement phase.

Not that long ago, for many patients a referral to ‘palliative care’ represented ‘being thrown on the scrapheap’, and for many doctors it represented defeat. Palliative care was care that was delivered when everything else had been tried. It was simple and kind, but it also represented failure: the failure of a healthcare system devoted to cure, and the failure of a body that could no longer recover and be rehabilitated. However, the aims and spirit that developed palliative care were very different from that dismal viewpoint, and the particular benefits of this type of care are beginning to be seen as appropriate in many different settings.

The ‘traditional’ recipient of palliative care is the cancer patient who has reached the end of their curative treatments such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy and who now relies on symptom control measures to provide an optimised quality of life and as much comfort as possible in the terminal phase. However, in recent years, the profile of patients being accepted onto palliative care services has expanded from exclusively cancer patients to a greater variety of conditions including end-stage organ failure and neurodegenerative diseases such as motor neurone disease.

Services differ on their specific criteria for acceptance into a palliative care programme. Some services happily accept patients with severe dementia, chronic obstructive airway (pulmonary) disease or severe stroke, whilst others are more reluctant to take such a broad spectrum of patients. Many palliative care services operate both inpatient and community outreach services and may have different admission criteria for each.

Services that provide a consultation service for other medical specialties may see all patients referred to them and give advice, but may only accept a proportion of those patients as ‘palliative care patients’. In many areas, ‘palliative care’ is now instituted in tandem with continuing active treatment such as chemotherapy. As the disease progresses, the care focus gradually shifts from being predominantly cure-focused to being totally palliative. Contemporary palliative care recognises that the transition to a palliative approach is difficult for the patient, the family, the carers, and the treating team, and that gradual introduction and transition is preferable to sudden change.

In the last decade, palliative medicine has become a medical speciality in its own right, and tertiary centres manage patients with difficult and complex symptoms who cannot be optimally managed in the community or on general wards. These centres aim to provide education and support for all healthcare staff who look after patients for whom the focus of care is no longer simply cure.

The modern concept that medicine is a ‘curative art’ is just that – very modern. For most of medicine’s history, the best that could be done was to alleviate symptoms and provide comfort. The opportunity to ‘cure’ has only come with the advent of agents to fight infection and the skill to perform specific curative surgical techniques. As medical advancement continued at a rapid pace, the focus of medicine shifted from providing care and comfort to the contemporary aims of scientific, evidence-based investigation, diagnosis and treatment aimed at cure. There were always places that cared for the dying, but, as modern medicine gained momentum, care for the dying became a low priority. Even today, it is much easier to raise money to buy expensive equipment to treat a very rare disease that affects the young than it is to provide care for the dying. This sheds an interesting light on priorities in modern society, given that we all have a 100% chance of dying in this lifetime!

The modern hospice movement really began in England in the late 1960s and 1970s, inspired by the work of the indomitable Dame Cicely Saunders at St Christopher’s in London, whose dedication, insight and passion still informs contemporary palliative care (Saunders 1990).

The Liverpool Care Pathway for the Dying Patient was developed in the UK in the late 1990s. This protocol has since been modified by centres across the globe to provide a framework that enables nurses and doctors to optimise the management of the terminal phase for their inpatients. However, outside acute hospitals, there is a great need for guidance on terminal phase management. As a relatively new specialty, palliative care is perhaps still ‘finding its place’ in many centres but the approaches it offers are being rapidly integrated into the care of an ever-wider patient population.

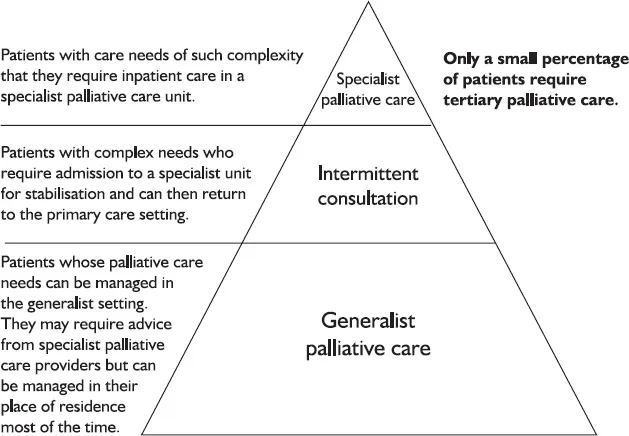

Not everyone who dies requires the expertise of a tertiary or specialist palliative care service. Specialist units are used for patients who have complex needs and problematic symptoms, and particularly for patients with escalating opiate requirements. These patients are not the ones referred to in this book. However, all patients will die at some stage, and for many of those patients death is expected. For these patients, and their carers, the palliative approach has much to offer and they are the focus of this book.

Figure 1.1 What type of palliative care is required?

Chapter 2

The palliative approach

In simple terms, the palliative approach is a way of thinking about quality-focused care rather than cure-focused care. It is also a term used to gently distinguish those patients whose symptoms can be managed in a general setting from those who require the specialist care implied by the medical term ‘palliative care’. The distinction is often an arbitrary one. This book therefore focuses on optimising the provision of supportive and palliative care for all patients for whom death is expected (be that in days, weeks, months or even years), who do not require the expertise of a specialist intensive palliative care unit.

Having to decide when and whether a palliative approach is appropriate often involves complex and emotive issues. The best scenario is that such a decision evolves organically, rather than being suddenly imposed in a crisis. This organic approach informs many of the assessment tools being introduced in care facilities for the elderly and it is a core value in living wills (also known as advance care directives).

However, in some cases, palliative care has to be provided as an acute response. Such situations might include, for example, deciding not to offer neurosurgical intervention in the case of sudden intracerebral haemorrhage, or deciding to provide comfort-only care in a case of sudden fulminant sepsis despite intravenous antibiotics. Instances of such acute palliative care intervention, and their complex ethical and legal dimensions, are beyond the scope of this book (see Further reading and references, page 111).

For most patients, death is heralded long before it actually occurs and it is for these patients that the palliative approach holds great potential benefit. But we must, of course, guard against oversimplification. The ‘palliative approach’ is often viewed as a philosophy that guides the levels of investigation and intervention that a certain patient wishes to receive. For instance, it may be cited as a reason for not transferring a patient from a care facility for the elderly to an acute hospital, for commencing oral rather than intramuscular or intravenous antibiotics in the face of a worsening infection, or for not considering surgical intervention. However, it is important for a palliative approach to remain patient-centred from the outset and not become a vehicle for other, veiled, agendas.

It is the duty of every healthcare professional to consider not just every patient, but also every episode in the care of each patient. For example, wanting to pursue the palliative approach in the care of an 85-year-old man with moderate dementia does not negate the fact that the single best way to manage his pain due to a fracture may be orthopaedic intervention. On the other hand, it may be entirely appropriate to use the palliative approach to prevent the same patient’s transfer away from his familiar surroundings to an acute hospital during his terminal phase, but high-dose antibiotic therapy may still be the optimal treatment for painful parotiditis (salivary gland infection).

No ‘blanket directive’ can ever encompass every situation a patient may face. The benefits of a palliative approach must therefore be vigilantly assessed at each new step in a patient’s journey, rather than simply at the outset. A particular care path must never be used to legitimise non-patient-focused agendas such as the need to deal with shortages of staff or resources, over-complex paperwork or institutional politics.

The opinion of competent patients, and their family members or designated advocates or surrogate decision-makers, should be regularly sought to ensure that no changes have occurred and there is no new desire to pursue more active treatment, even if the care team members believe that this would be futile. The patient and their family have the right to change their minds. They also, once fully informed, have the right to make the ‘wrong’ decision! At every step along the way, the central question/s should be asked: ‘Is this what the patient wants?’ and/or ‘Is this the best way to optimise quality of life, comfort and dignity for this patient at this time?’ Only when the patient’s best interests lie at the heart of each decision can we be sure that our clinical duty of care (and our ethical and moral responsibility to the patient) is at one with the care approach we are using, palliative or otherwise.

It is impossible to create a list of all patients for whom the palliative approach may be appropriate. To consider only the dying ignores many other patients for whom palliative care can be of great benefit. In general terms, patients who fall into the following categories should be reviewed:

• Patients in the final weeks, days or hours of life

• Patients with advanced or metastatic malignancy who have no further treatment options or who have declined further treatment

• Patients with malignancy who are approaching a transition from curative to palliative care

• Patients with symptomatic deterioration during maximal medical treatment for heart, liver or lung failure

• Patients with end-stage renal disease, or dialysis patients with declining response to dialysis or who express a desire to cease treatment

• Patients with advanced or end-stage dementia

• The ‘oldest old’

• Patients with complex co-morbidities whose quality of life and function continues to decline despite repeated intervention

• Patients with incurable, far advanced and/or progressive neurological compromise

• Patients who have been unable to recover cognitive and physical function following an event such as a cerebral vascular accident or a myocardial infarct

• Patients with complex care needs such as those who have profound intellectual and physical disabilities

When considering which patients are suitable for a palliative approach to care, the following broad categories should be explored:

• Patient wishes

• Family and carer wishes

• Medical issues

• Disease stage

• Life stage

Patient wishes

If the patient is mentally competent and – after effective discussion – does not agree with the adoption of the palliative approach, this should be clearly documented and the ‘normal’ pattern of care continued without further delay. The issue may, of course, be revisited but the statutes of informed consent, patient autonomy and confidentiality that inform all clinical practice are just as relevant when discussing the issue of palliative care as they are in other clinical domains.

All palliative care practitioners have had the experience of arriving to review a patient after a request for consultation has been received – only to find that the patient is not only unaware of the review but is unaware of the proposed withdrawal of curative treatment. Any refer...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- About the author

- Introduction

- 1. What is palliative care?

- 2. The palliative approach

- 3. Care of the elderly and dementia

- 4. Old age

- 5. Death and dying

- 6. Malignancy

- 7. Organ failure

- 8. Neurodegenerative disorders

- 9. The rise of chronic disease and the ‘oldest old’

- 10. Recognising and treating the dying patient

- 11. Medical treatment versus medical care

- 12. The good referral

- 13. Grief and loss

- 14. Caring for the carer

- 15. Difficult discussions

- 16. The angel at the end of the bed

- Appendix: Case studies

- Index