![]()

Chapter one

Preparation for Study

Undertaking a programme of study as an adult involves becoming an active participant in the learning process. It cannot be assumed that everything required will be taught. Learning does not occur by osmosis but by the involved commitment of all concerned. Fortunately for students in the twenty-first century, educators recognise the need to involve students, and many professionals have developed tried and tested methods to be used as tools for learning. As with everything, it would be churlish not to use these methods, particularly if there is one method that suits your particular learning style. Also, as with any learning, it is never enough merely to read about the topic. In order to ensure learning takes place, the student has to engage with the material or learning tool, practise using it and become comfortable with it. An example here that is unrelated to study in a formal way is my husband’s attempts to complete Sudoku puzzles. An avid Sudoku puzzler myself, it takes me a matter of minutes to complete a moderately hard puzzle. My husband, after noting my enjoyment, decided he wanted some of that pleasure and attempted his first puzzle. After several hours on an easy puzzle he gave up in frustration, unable to complete it, even with tips from me. Some time later, trying again, he was dismayed to find he still could not do these puzzles, and was not impressed when I informed him that his inability to complete them came down to his lack of practice at actually doing them. He needs to practise them regularly in order to learn the process. Practice does make perfect. My husband still only attempts them once in a while and still suffers the frustration of non-achievement.

Spend some time looking into techniques that make your own life easier. Practise using different methods, such as lists, a notice board, mind mapping or timetables (see Chapter 1 and Chapter 3). Practise reading, note-taking, storing and retrieving material. Practise writing, paraphrasing and referencing. They are all skills to develop through your periods of study and all require practice. Try not to fall into the trap of photocopying tools, articles and materials that may prove to be useful – and then never get round to actually using them.

Naturally, there are many other practical tools you can use to prepare yourself for study. Organisation and planning will become prime aspects of your life from now on. The sooner you develop these skills, the sooner you will become comfortable with your learning schedules. It sounds a simple idea to get yourself organised, but again actually ‘doing it’ takes time. It needs thinking through and explaining to all the people who share your life.

Learning styles

A good starting place is to explore your individual learning style. A search on the internet will reveal many questionnaire tests with printable advice to facilitate your learning. It would be advisable to revisit and review these as you progress through your course. Discovering your own learning style will enable you to select methods and tools that suit you. They will make life easier, but again you will need to explore them fully and practise your preferred methods in order to make them work for you. Learning is like riding a bike – very difficult initially, but improvements can be seen with practice; and even if we do not continue the activity, once learnt, the skills can be revised and used forever. Now try the exercise in Activity 1.1.

Activity 1.1

Search for a learning styles tool on the internet. Complete the questionnaire and print out the result. Consider for a while what the result says about your own individual style. Do the suggested methods for learning suit you? Do you recognise them? Can you use them to aid your learning?

Activity A

Select one of the learning methods you are familiar with and use it to plan an essay about your work role. The essay should be a descriptive overview of what your role encompasses, the tasks undertaken, who you report to, and so on.

Plan what you would need to include.

For instance, if using a list it may include:

• The title of your role.

• Who you report to.

• Who you are responsible for.

• Tasks undertaken (this could be quite extensive).

• Your extended role.

• Your opportunities within the role.

Activity B

Now select a tool that you are not as familiar with and plan your essay using that tool.

Which one was easier to use?

Which one do you think will encourage you to research material further?

Which one makes you want to actually write the piece?

Explore the methods suggested throughout this chapter and experiment with them to develop and utilise your individual learning style.

|

Remember… |

| just reading about learning styles will not make life easier for you – only putting the associated tools to use will. |

Organising your work

Space

Having a place to keep study materials enables students to be organised and be prepared for taught sessions. If you do not have a specific room to use as a study then you need somewhere in your home that you will be able to make into your own space: the dining room table, a spare bedroom or a kitchen table – whatever suits you best. If it is an area that has to be used by other people then you will need a large box in order to pack things away. As most of us need to use space occupied by others, a system for setting things out and packing them away will save time and reduce stress when searching for things. If you are lucky enough to have a study then you will only need to organise the space into a good working environment. Remember to discuss this with other members of your family in order to gain their understanding of your need for organisation. It will also make them more supportive of you if you involve them in these types of decisions. A time may come when you need to delegate tasks, and this will encourage them to support your learning (see Time management below).

As healthcare professionals you should also be aware of all health and safety aspects, such as moving and handling, and you may need to revise safety issues regarding computers. A search on the internet will provide useful information regarding the health aspects of sitting at a computer, or you can contact the IT specialist at your place of work or college for advice.

The space you choose for study will need good lighting and comfortable seating and there should be minimal interruptions. You will need access to writing equipment, books and journals, and a computer for word-processing and internet access. A good tip is not to allow telephones in your study space, as the temptation to answer a call from a friend who is bound to have something important to discuss can be overwhelming. Missed calls can always be caught up on later, when you are ready for some distraction.

Storage

You can use folders, box files, index cards or just a large cardboard box to store things in. As long as you list the items in some ordered way (such as alphabetically or in date order), you will be able to find anything you need at any time. You will need to carefully store all your returned assignments as evidence of completion, and some may be useful for your competency work. The modules on the foundation degree programme often overlap, so completed assignments may be useful for refreshing your memory of theoretical concepts. Feedback on your assignments will also become a useful tool for planning future assignments, so you will need access to returned work whenever you are planning for the next round of assignments (see Chapter 3). Books borrowed from libraries will need to be returned by a set date and I always find it useful to enter the return date in my diary to avoid overdue fines. I have heard of overdue fees amounting to over £30 so being organised here will save you money!

Time management

We all need time to study, but people often underestimate the amount of time required for research and assignment writing. As a student it will be advantageous to make sure that the people you live with are aware of what study time means to you. Partners or children will interrupt with questions, and the phone will need answering, as will the door. All these create distractions and disturb your study time, and it can be very difficult to return to your books following a distraction. As a student, there is nothing worse than being deeply involved in a piece of writing and being disrupted by a minor distraction, when all that was needed was a little cooperation. The foundation degree programme is very time-consuming so involve close family members from the start, explaining that it is for two years. Planning a family treat at the end will encourage them to support you.

The easy way to deal with time issues is to:

• Talk to family and friends. Explain how important your study time is, bargain for babysitting or cooking, and ensure you get people on your side to support you.

• Delegate household tasks wherever possible. You may need to negotiate, depending on your arrangements, but a previously planned reward at the end of the programme may help.

• Be specific about the times you will study. Make sure everyone knows when you would prefer not to be interrupted, and use that time wisely.

• Always have an end time for your study periods so that others know when you will be free again.

• Ignore the telephone or doorbell – you can always call people back later. They will understand and will want to support you.

• Time your study sessions and plan your work to fit the time available. You will need to build in breaks to relieve the pressure, but these also should be timed to avoid time wasting. Procrastination leads to panic!

• Keep your timetable in a prominent place so that others can see what you are doing rather than interrupting you to ask if you are busy.

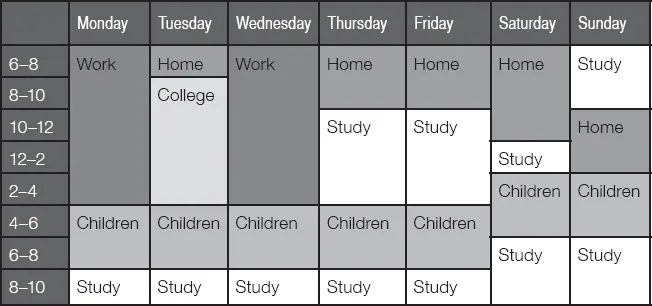

Try creating a timetable of a typical week to see where you can plan to study. The chart in Fig. 1.1 (see p. 6) looks impressive, showing a time and place for every function. However, this student has built in no time for rest and relaxation, and these are very important while studying. You will need plenty of ‘me time’ in order to recharge your batteries and keep working productively. A good exercise would be to create several timetables to cover the varied shift patterns that you may encounter as a healthcare worker. Include college days and time with your family, as well as study time, reading time, and the all-important relaxation time. Make sure that you reward yourself regularly, to recharge your batteries and provide motivation when the going gets tough.

Fig. 1.1: A sample student’s weekly timetable, including ‘home’ time (for cooking, cleaning, shopping, DIY, gardening), ‘children’ time, and ‘study’ time (time that is available for study).

Equipment and resources

All the usual office-type materials will be useful when studying – folders, lined paper, pens, pencils, paperclips, a stapler, hole punch, and paper and ink for your printer, to name a few. You will not need all of these at the outset of the programme so spread the cost over time, buying supplies as and when you need them. A good notebook will definitely be required straight away, as the teaching will commence on day one and note-taking will be an important skill to develop from the outset (see Chapter 3). All assignments for universities have to be word-processed. Computer skills, although perhaps a little daunting at first, can soon be acquired through practice. This type of activity requires you to have a go, playing with all the options in order to familiarise yourself with them well enough to use them effectively. You could get a lesson or two, to learn about setting up a page, font types and sizes, word counts, justification, line spacing and page breaks. You will also need to be able to send and receive emails with attachments and, of course, to save them to a folder.

Working on a computer can be time-consuming initially but you will be surprised how quickly your skills will develop. The health and safety aspects need to be observed and there are many guides on the market to help you develop these much-needed skills. Some people prefer to proofread their work from hard (paper) copy, so try to save paper by re-using your print sheets (but be careful that you do not get confused about which piece you are reading!). One top tip is to make sure you always have a spare printer cartridge to hand. Running out of printer ink is a poor excuse for non-submission of work and many institutions will not accept it. Another good tip is to keep a notebook and pen with you at all times. As a student, I often struggled to find the words to describe a concept and then, when I least expected it, the words came to mind – usually in a totally unsuitable place, like a supermarket, the dentist’s waiting room or on the bus travelling home from work. A small notebook and pen, which can be easily stored in a pocket or bag, will prevent that awful feeling when you return from the supermarket and cannot recall those much-needed and obviously exceptional words.

![]()

Chapter two

Preparation for Change

As a healthcare worker about to commence the trainee assistant practitioner (TAP) programme, you need to be prepared to be changed. There is no way to measure the changes that will take place, but you will find out that life will never be the same again. Having spoken to students throughout their training and on completion, I have been privileged to share in the acknowledgement of change. It is very difficult to quantify, however. It most definitely does occur and I genuinely believe it is for the better. One student, mid-way through her second year of the programme, stated: ‘I did things – even if I was unsure – because I was told to. Now I don’t. I do things I know I am capable of doing and refuse when asked to do things I do not understand.’

Where once, as a healthcare worker, you functioned in the workplace because ‘that was how it was done’, you will begin to question what you do on a daily basis. You will search for the reasoning and evidence behind your actions and ensure that your practice is grounded in theory for the good of the client. As a trainee assistant practitioner, you will become a reflective practitioner, with the knowledge and skills to practise as a professional. You will have the wherewithal to challenge poor practice, and the resou...