- 154 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Since 2006, the management of chronic kidney disease (CKD) has become part of routine primary care practice. This book offers primary care practitioners a clinically based, practical understanding of how to diagnose and manage kidney disease (and what this means for the patient). It also fills the gap between the recent plethora of guidelines, protocols and recommendations on CKD and the questions patients ask in everyday clinical practice. Armed with this deeper understanding, healthcare professionals without specialist training in nephrology will be sufficiently informed to be able to manage renal disease with greater safety, effectiveness and efficiency.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Understanding Chronic Kidney Disease by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Diseases & Allergies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Why chronic kidney disease has

become such an important issue

‘I never bothered to learn about renal disease because I never wanted to be a nephrologist.’

Anonymous senior house officer, Portsmouth, 2005

Prior to 2006, chronic kidney disease (CKD) was very definitely an issue for the specialist. Should a primary care physician chance upon a patient whose blood tests suggested impaired kidney function, a referral was immediately sent to the local nephrologist, who would investigate, try to establish the underlying cause and thereafter keep the patient under regular review in the hospital outpatient clinic. The patient’s general practitioner was encouraged not to interfere, but would occasionally receive a letter from a transient renal senior house officer to say that the patient was stable and would be reviewed in the renal clinic in six months’ time. This system guaranteed that patients were never seen by the same junior doctor twice, and no one had the confidence to discharge them.

Of the patients with CKD under specialist follow-up, a small fraction might progress to the stage where they required renal replacement therapy in the form of dialysis or transplantation. Once they were receiving these modalities of treatment, the GP was effectively excluded from the process and patients were warned not to seek medical attention from anyone who did not work in their renal unit. GPs learned their lesson well, and knew not to dabble with (what were now) the renal unit’s patients. However, this cosy arrangement has now become unsustainable.

Why primary care became involved in managing CKD

The major pressures which led to the involvement of primary care in managing patients with CKD were the need to save money and the emergence of a new understanding of the epidemiology and relevance of CKD. This can be summarised under three broad headings.

1.The need to reduce the amount of money spent on dialysis

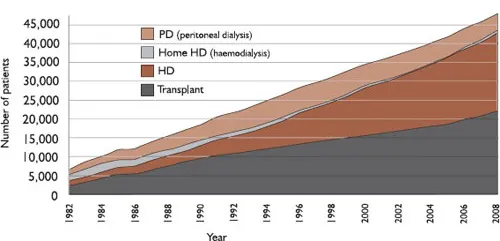

Since the 1980s, there had been a huge increase in the number of patients on renal replacement programmes (see Figure 1.1). As dialysis costs between £20,000 and £30,000 per patient per year (depending on modality), any intervention that might lead to a decrease in demand was clearly economically desirable. In order to have any impact on the prevalence of end-stage kidney disease, management of CKD would need to be initiated at the earliest stage. Accordingly, the NHS needed: (i) a means of identifying people at risk of developing CKD; (ii) a systematic targeted screening programme; and (iii) early implementation of measures to reduce the rate of progression.

Figure 1.1 Growth in prevalent patients by modality in the United Kingdom 1982–2008 (UK Renal Registry 13th Annual Report, 2011). Note that the growth in the prevalence of transplantation has not kept pace with the overall growth in patients with end-stage kidney disease. This shortfall has largely been taken up by hospital-based haemodialysis – an expensive alternative.

As primary care was becoming increasingly proficient at identifying people with hypertension and diabetes (both of which are associated with CKD progression), it was a small step to add monitoring of CKD to this list. Moreover, effective management of disease progression could easily be incorporated into existing primary-care-based public health programmes. It therefore seemed that primary care was ideally placed to make a favourable impact on the prevalence of end-stage kidney disease and thereby stem the growth of the dialysis population.

2.New appreciation of the prevalence of CKD

Large population studies indicated that early CKD (i.e. before dialysis is inevitable) may be a major public health issue. Far from being a niche specialty concern, it appeared that about 10% of the adult population had CKD and that most of this was undiagnosed. Several authors spoke of an ‘epidemic of CKD’. In addition to being a risk factor for kidney failure and dialysis, CKD was now seen as a major independent risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease. Since general practitioners were already heavily involved in cardiovascular risk modification, they needed to know about this hitherto unrecognised risk factor and deal with it in the context of public health as a whole.

3.New healthcare policy

A new guiding principle of NHS reform began to emerge: that patient care should be shifted, as much as possible, away from hospitals and into the community. This arrangement came to be considered more convenient for patients and less demanding of financial resources. During this time, renal units themselves were struggling to keep up with the demands placed upon them by a rising number of patients requiring renal replacement therapy. With resources stretched, it seemed sensible to identify those patients who derived the least benefit from an expensive, high-tech renal unit and to discharge them to their general practitioners with clear instructions on how they should be managed. And if these individuals could be managed in primary care, so too could newly identified patients with similar low-tech medical requirements. The days of renal units accumulating patients with CKD for six-monthly review by a junior doctor were at an end. From now on the GPs would need to take over.

Education and engagement of primary care: NSF, QOF and NICE

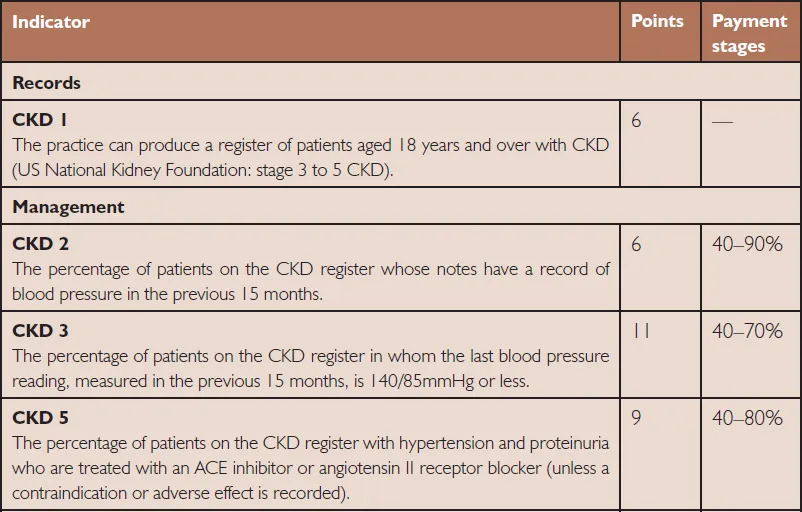

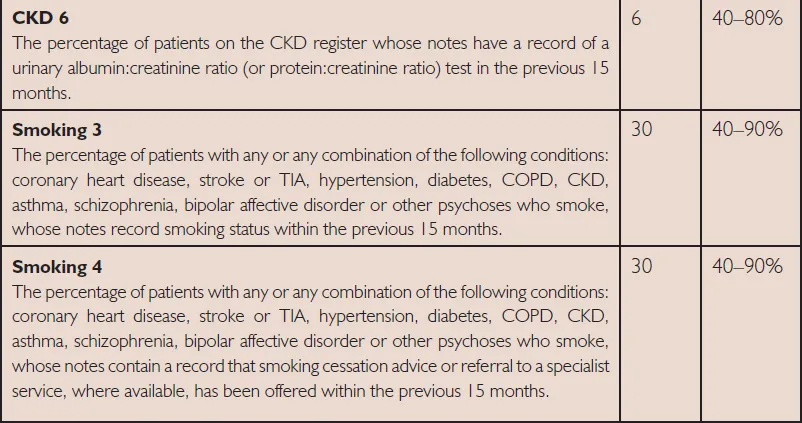

Under the influence of the factors described above, in 2005 the Department of Health published The National Service Framework for Renal Services Part 2: Chronic Kidney Disease, Acute Renal Failure and End of Life Care. This policy document required a volte face in existing management pathways. Instead of serendipitous identification of CKD, followed by immediate referral to a specialist, GPs were now expected to set up systematic programmes to identify CKD and manage it in the community. To facilitate this change, certain indicators relating to CKD were simultaneously incorporated into the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF), which determined remuneration to primary care practices. Exactly how the QOF functions is outside the remit of this book, but essentially points are awarded to primary care practices for achieving a specified outcome in a given percentage of their patients. Attainment of these points determines the flow of income to the practice. Table 1.1 shows the QOF points relevant to CKD.

Table 1.1 Indicators related to chronic kidney disease in the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) of the General Medical Services (GMS) contract.

Almost overnight and with very little warning, GPs were faced with new responsibility for a disease (now defined by an unfamiliar test, the estimated GFR), which had always been the preserve of the local renal unit. What is more, their new employment contract (and thus their income) relied on them managing it according to defined standards.

Nephrologists realised that primary care practitioners would require some easily understood guidelines to increase understanding of what was required. Most renal units wrote their own guidelines and provided resources to their local GPs, but the need for consistent national guidelines was obvious. Accordingly, in 2008, the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) published Guideline 73: Early Identification and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease in Adults in Primary and Secondary Care, which provided an accepted standard for how CKD should be managed in a primary care setting. It recommended that patients at high risk of having unrecognised CKD should be targeted for testing.

NICE guidance on situations in which patients should be routinely tested for the presence of CKD (note that old age and obesity are not included)

•Diabetes

•Hypertension

•Cardiovascular disease (ischaemic heart disease, chronic heart failure, peripheral vascular disease and cerebral vascular disease)

•Structural renal tract disease, renal calculi or prostatic hypertrophy

•Multisystem diseases with potential kidney involvement – for example, systemic lupus erythematosus

•Family history of stage 5 CKD or hereditary kidney disease

•Opportunistic detection of haematuria or proteinuria.

Once CKD was identified, the NICE guideline described how the condition should be effectively managed in primary care, and when patients should be referred for specialist input. The guideline had the virtue of clarity, but it recognised that robust evidence to support some of the recommendations was lacking. As evidence relating to management of CKD continues to accumulate, other organisations have developed their own guidelines, notably the Renal Association in 2010 and the international organisation Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) in 2012. NICE itself is in the process of renewing its 2008 advice, and is likely to change some of its previous recommendations.

Why it is so important for primary care practitioners to know about CKD

Since 2006, the management of CKD has become embedded in routine primary care practice. Whilst there is great variability in the success with which practices identify patients with CKD and place them on their CKD register, it is generally accepted that GPs have made great strides in assimilating this new responsibility. Nonetheless, as detection of individuals meeting the necessary criteria for a diagnosis of CKD has increased, one hears new questions from general practitioners on a regular basis – ‘Surely these apparently well, elderly patients with low eGFRs can’t all have significant major organ failure?’ ‘Do these osteoporotic ladies in the nursing home really benefit from having their blood pressure lowered to 130/70?’ ‘Since the holiday insurance company is going to quadruple her premiums, is it really in the interests of an apparently healthy lady to be told she has CKD stage 3 (not merely stage 1 or 2 but STAGE THREE, how worrying!)?’

There is no simple answer to these questions – certainly nothing evidence-based that can be slipped into a palatable guideline. It is therefore necessary for all healthcare professionals to develop an understanding of the means by which CKD is diagnosed and how it can be managed. CKD is now considered a greater public health issue than was previously thought, and there must be a commensurate improvement in the level of understanding of renal disease within the mainstream of basic medical knowledge. Without this knowledge, we are likely to end up with misinformed patients, inappropriate referral to specialists and poor use of precious financial resources.

What is the purpose of this book?

The anonymous medical senior house officer quoted at the start of this chapter was (I hope) the last of a generation who were conditioned to send all renal issues unquestioningly up the line, into the eager arms of the nephrologist. We all know this is bad medicine. His successors will need a clinically based, practical understanding of how to diagnose and manage kidney disease (and what this means for the patient). What no one requires is to be force-fed tubular pathophysiology, podocyte molecular biology or the histology of glomerulonephritis. All these aspects are now covered in renal postgraduate courses; and all of them are, to the non-specialist, stupefyingly boring and completely irrelevant.

This book simply aims to increase understanding of what lies behind the recent plethora of guidelines, protocols and recommendations. It also sets out to fill the gap between the instructions in these documents an...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- About the Author

- Dedication

- 1 Why chronic kidney disease has become such an important issue

- 2 The definition and classification of CKD

- 3 Normal kidney function and what goes wrong in CKD

- 4 Estimated GFR: Is it a good measure of renal function?

- 5 Tests for proteinuria: What do they all mean?

- 6 CKD as a marker of cardiovascular risk

- 7 Kidney function in older people: CKD or benign decline?

- 8 The first step in management: Establishing the cause of CKD

- 9 Preventing progression of CKD: Hypertension and ACE-inhibitors

- 10 When renal function takes a dip

- 11 Long-term systemic effects of CKD: Blood and bones

- 12 Diet and nutrition in CKD

- 13 Managing heart disease in the context of CKD

- 14 Diabetes and renal disease

- 15 Fertility and pregnancy in the context of CKD

- 16 Medicines management in CKD

- 17 When all else fails: Management of end-stage renal disease

- 18 Symptom control and end-of-life care in CKD

- 19 Management and referral: A quick reference summary

- Index